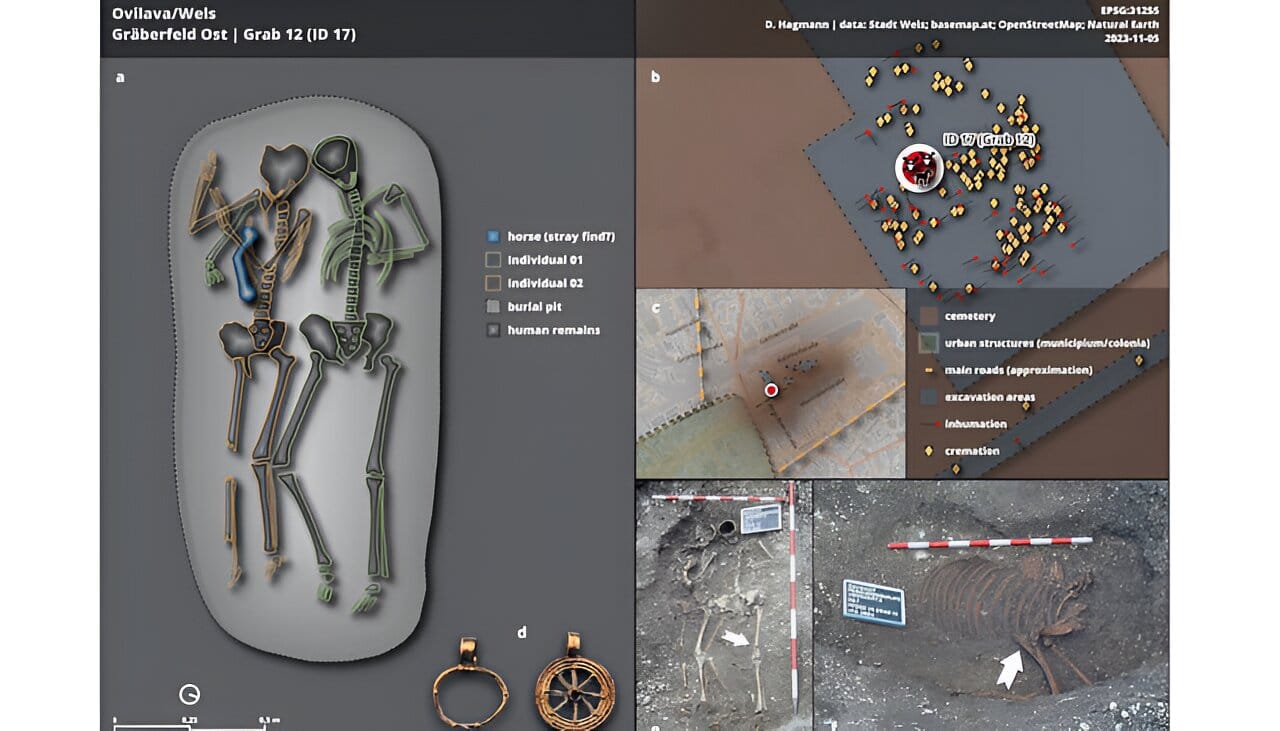

Two decades ago, under the clang of machines and the rhythm of construction in modern Wels, Austria, something ancient stirred from its slumber. Buried beneath layers of soil and time, a grave was unearthed—one that would puzzle archaeologists for twenty years. In the quiet field once known as the eastern burial ground of the ancient Roman city of Ovilava, the remains of two humans lay entwined in what looked like an eternal embrace. Near them, the bones of a horse rested solemnly.

The discovery was so unusual that archaeologists first believed it must belong to the early medieval period. The scene—a double human burial with a horse—hinted at a romanticized warrior past, perhaps a noble couple entombed with their trusted steed. But science had more to say. And as the decades passed and the tools of archaeology advanced, the grave slowly began to whisper its secrets.

Now, with the application of cutting-edge bioarchaeological and genetic technologies, the mystery has been solved. And the truth, as is often the case with archaeology, is both stranger and more poignant than fiction.

Not Lovers, But Kin

The grave, originally misdated by nearly half a millennium, has now been identified as a Roman-era burial from the 2nd to 3rd century CE—centuries before it was first believed to have been made. Through careful osteological studies and a revolutionary analysis of ancient DNA (aDNA), scientists from the University of Vienna, led by anthropologist Sylvia Kirchengast and archaeologist Dominik Hagmann, discovered something unprecedented in Austrian archaeology.

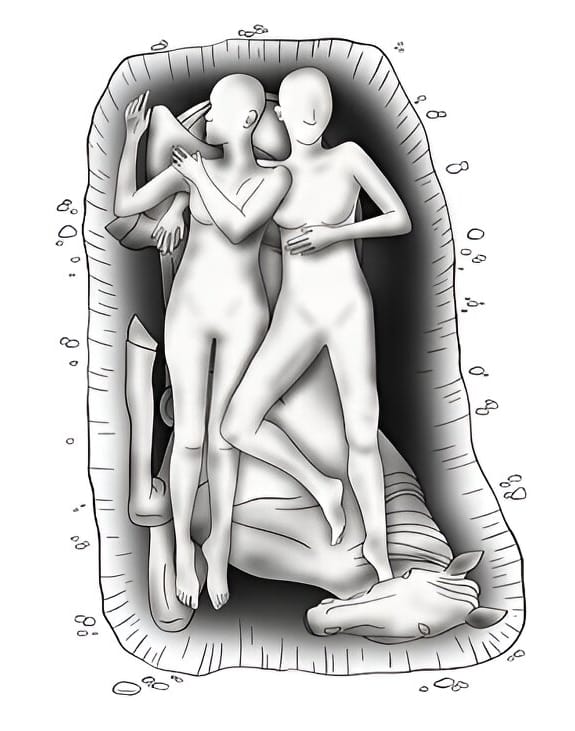

The two individuals buried together were not a couple. They were not warriors. They were not part of some early medieval legend. They were a mother and daughter—buried together during the Roman Empire, in what is now Austria, over 1,800 years ago.

This identification is not only touching in its emotional intimacy—it is also scientifically groundbreaking. It marks the first confirmed biological mother–daughter burial from Roman antiquity in Austria discovered through genetic evidence.

Science Breathes New Life Into the Past

The confirmation was made possible by combining ancient DNA extraction techniques with radiocarbon dating and osteological examination. DNA revealed their familial relationship. Radiocarbon analysis recalibrated the age of the burial to the Roman Imperial period, correcting the long-standing assumption of a medieval origin.

The bones told more stories than family ties. The older woman, estimated to be between 40 and 60 years old, showed skeletal indicators consistent with frequent horseback riding. Her daughter, likely aged between 20 and 25, was also buried with dignity and care. The presence of golden grave goods—perhaps jewelry or ceremonial items—further hinted at a family of elevated status, perhaps part of the Romanized provincial elite in Noricum, the Roman province that included parts of modern Austria.

The careful burial of the women with a horse, an animal rare in Roman graves, added further complexity. It suggested a blend of traditions—Roman funeral rites mingled with older, regional Iron Age customs where horses were often included in burial practices. In this quiet patch of Wels, cultures had converged in a single, unforgettable act of remembrance.

The Horse That Stood Watch

The inclusion of a horse was not only symbolic; it also carried cultural weight. In the Roman Empire, animals were rarely buried with humans, especially not within the same grave. Horses, expensive and vital creatures, were more often part of military or ceremonial life. The fact that this family was buried with one hints at status, symbolism, and perhaps sorrow.

Archaeozoological analysis—the study of animal remains in archaeological contexts—showed that this was no ordinary workhorse. The horse may have belonged to the older woman, used for travel or ceremonial display. The wear patterns in her skeletal remains suggest a life spent on horseback, her body molded by motion and the steady rhythm of riding. In life, she may have been someone who moved across landscapes, who traveled with grace or purpose. In death, she and her daughter were laid to rest with the animal that once carried her, their journey ending together.

A Death, a Tradition, a Farewell

No written texts, carvings, or inscriptions accompanied the grave. But the arrangement, the posture, the artifacts—all formed a language of their own.

Why were mother and daughter buried at the same time? The evidence suggests the possibility of disease, perhaps a sudden illness that claimed both lives close together. The simultaneous burial and the care with which their remains were interred suggest a community effort—a ritual, perhaps, of sorrow and remembrance. The burial style recalled elements of pre-Roman traditions, even as it existed within the framework of Roman provincial society.

The gold, the horse, the careful placement—it was a farewell spoken in gesture rather than words. And for centuries, it remained silent beneath the soil.

From Lost to Found: The Role of Modern Science

What makes this grave especially significant isn’t just its age, or even its rarity. It’s the technology that allowed its true story to be told.

Thanks to bioarchaeology—a multidisciplinary field that blends biology with archaeological science—and advances in ancient DNA sequencing, the team could go beyond surface interpretations. They didn’t just look at bones. They extracted the essence of who these people were: their age, their health, their relationship, and even how they might have lived.

This is a striking reminder of how archaeology has evolved. It’s no longer just about shovels and trowels. It’s about genome sequencing, isotope analysis, 3D reconstruction, and radiocarbon calibration. In the case of this Roman grave in Wels, it was a blend of the old and the new that finally let the past speak clearly.

Whispers From Roman Austria

In the grand sweep of Roman history, this burial may seem small. It doesn’t tell the tale of emperors or great battles. But it tells something deeper—the human story. The emotional thread that binds past and present.

A mother and daughter, now known across time, tell us about life and death in Roman Austria not through monuments, but through the intimate language of biology and burial. They show that love, family, and ritual transcended empire, and that even within the provinces of a sprawling Rome, people lived lives rich in meaning and complexity.

This discovery also helps historians and archaeologists better understand how Roman customs blended with local traditions in Noricum. The presence of the horse, the familial burial, and the associated grave goods suggest a society that did not merely adopt Roman ways, but adapted them—infusing them with local memory and identity.

Echoes Beneath Our Feet

Archaeology, at its best, isn’t just about discovering objects—it’s about rediscovering people. The grave in Wels is no longer just a collection of bones. It is a narrative of love, loss, heritage, and time.

As Dominik Hagmann and Sylvia Kirchengast concluded in their published report, this case demonstrates the enormous potential of combining modern science with traditional archaeological insight. And perhaps more importantly, it reminds us that history often lies just beneath our feet—waiting not only to be found, but to be understood.

The grave may be ancient. But the emotions it evokes—the bond between parent and child, the customs of farewell, the quiet endurance of memory—are timeless.

Reference: D. Hagmann et al, Double feature: First genetic evidence of a mother-daughter double burial in Roman period Austria, Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2024.104479