In the parched heat of northern Tanzania, in a place known as Olduvai Gorge, a fossil lay buried in silence for nearly two million years. Then, in 1959, a woman named Mary Leakey—part of the pioneering Leakey family of paleoanthropologists—unearthed something extraordinary. It was a skull, almost perfectly preserved. Its cheekbones were broad and flaring. Its molars were immense, bigger than any human had ever possessed. And at the top of its head was a peculiar crest—a ridge of bone where powerful jaw muscles had once anchored.

It was unlike anything seen before. This was not a modern human. This was not a chimpanzee. It was something else entirely. The discovery would later be called Paranthropus boisei, and it opened a door into a lost branch of the human family tree. A branch that ran parallel to our own for hundreds of thousands of years before fading into extinction.

But who was Paranthropus boisei? What kind of life did it live? And what does this muscular, wide-faced hominin tell us about our own survival as a species?

To answer that, we have to go back—not just to Olduvai Gorge—but to the African savannas and river valleys of a time long before civilization, before tools became sophisticated, and before Homo sapiens had even begun to dream.

Meeting Paranthropus boisei

Paranthropus boisei lived between roughly 2.3 and 1.2 million years ago, during the Pleistocene Epoch—a period marked by climate fluctuations, shifting habitats, and bursts of evolutionary change. It walked upright on two legs, just like we do, and likely stood between 3.5 and 4.5 feet tall. Males were considerably larger than females, a sign of sexual dimorphism—an evolutionary trait where one sex is physically more dominant, often due to mating competition or division of labor.

But its most striking features were not in its posture or height. They were in its face.

With a broad, dish-shaped face, enormous jaws, and molars nearly twice the size of a modern human’s, Paranthropus boisei looked built for chewing. Its sagittal crest—especially pronounced in males—indicated that this hominin had incredibly strong chewing muscles. Its zygomatic arches (cheekbones) flared outward, not just to support the muscles but to make space for them.

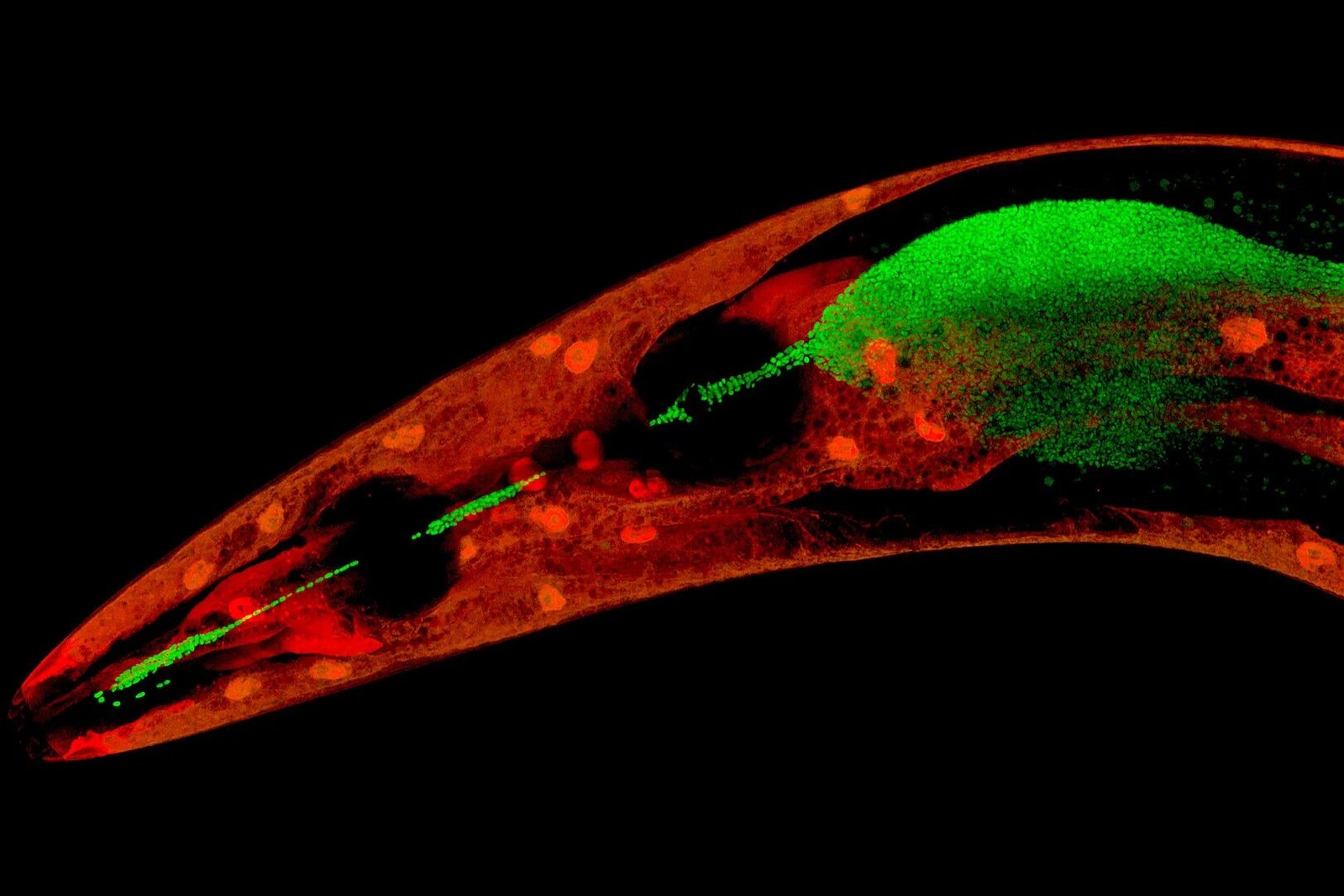

Its brain, by contrast, was small—averaging between 400 and 550 cubic centimeters, closer in size to that of a chimpanzee than a modern human. Despite its upright posture and bipedal gait, it lacked the cranial volume that would suggest complex abstract thinking or language.

This creature was not on the direct line to us. It was not an ancestor. It was a cousin.

A Chewing Machine in a Changing World

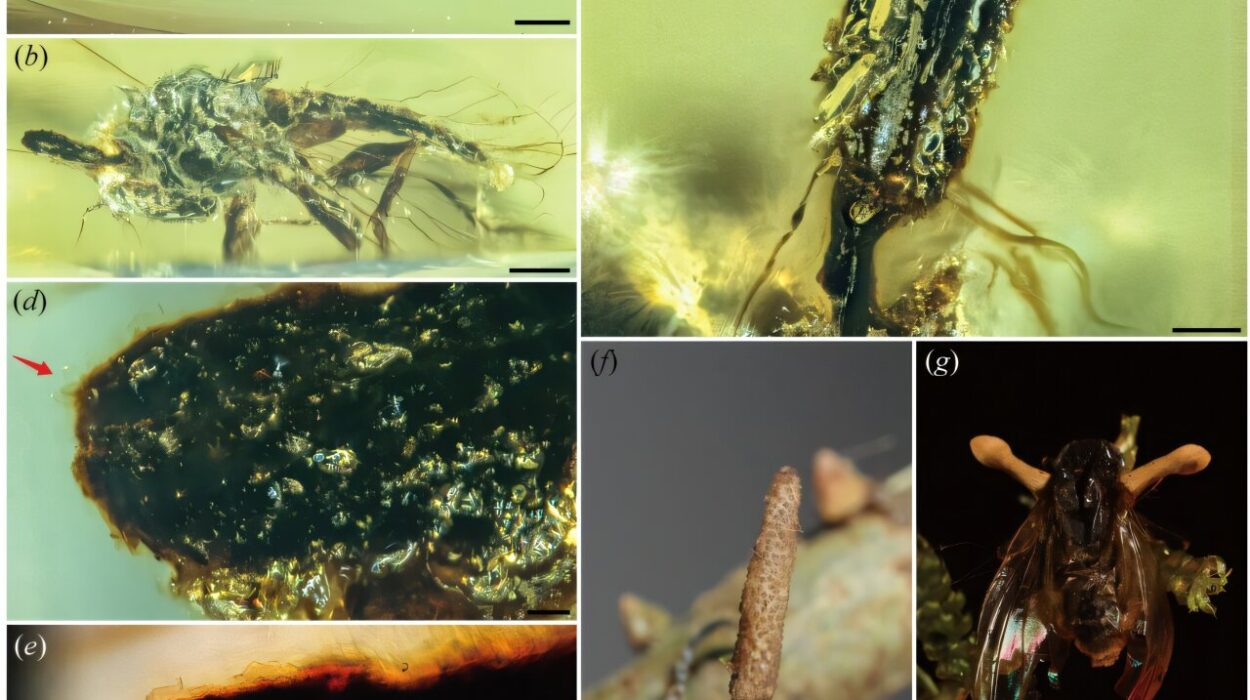

Why such a powerful jaw? The answer lies in diet. Fossilized teeth tell a gritty, fascinating story. By analyzing microwear patterns—tiny scratches and pits on the surface of molars—scientists can infer what kinds of food an animal was eating just before it died. In the case of Paranthropus boisei, those patterns showed it chewed hard objects, though not necessarily as regularly as one might think.

Further revelations came through isotope analysis—measuring the chemical signatures of carbon in fossilized tooth enamel. This revealed that Paranthropus boisei ate a diet heavily based on C4 plants—grasses and sedges, or perhaps the underground storage organs (tubers, roots) of those plants.

In other words, this hominin may have survived on what the environment gave in abundance: low-quality, tough vegetation, possibly supplemented by harder fallback foods like nuts or seeds when times were lean.

It had evolved, over generations, to become a specialist—one that could grind away day after day on fibrous plant material. But specialization can be dangerous in evolution. When the environment shifts, the specialist must adapt—or die.

A World of Many Hominins

It’s tempting to think of evolution as a linear story: apes become australopiths, australopiths become humans. But the real story is more like a branching tree, full of dead ends, side experiments, and evolutionary gambles. During the time Paranthropus boisei lived, it was not alone.

In fact, the African landscape was populated by multiple hominin species, coexisting—and perhaps competing—for resources. One of those species was Homo habilis, often dubbed “the handy man” for its association with the earliest known stone tools.

While Paranthropus boisei had the jaw of a grinder, Homo habilis had a more generalized skull, smaller teeth, and a slightly larger brain. More importantly, it showed signs of tool use and possibly even rudimentary culture.

For decades, paleoanthropologists debated whether Paranthropus boisei made tools as well. After all, it lived in the same areas where Oldowan tools—simple stone flakes and choppers—were found. But most evidence points to Homo habilis (and later Homo erectus) as the likely makers and users of those tools.

Paranthropus boisei, it seems, followed a different path. It relied on its anatomy rather than its intellect. It was a marvel of chewing efficiency—but perhaps limited in behavioral flexibility.

The Tragic Grace of Evolutionary Experiments

There’s something poignant about Paranthropus boisei. It had survived for over a million years—a duration longer than our own species has yet existed. It had adapted spectacularly to its ecological niche. It thrived across eastern Africa, from Ethiopia to Tanzania to Kenya. And then it vanished.

Sometime around 1.2 million years ago, Paranthropus boisei went extinct. The precise reasons remain unclear, but the likeliest culprits are environmental change and competition.

As Africa’s climate shifted, forests gave way to more open savannas. The types of plants Paranthropus boisei depended on may have become scarcer or more seasonal. Meanwhile, species like Homo erectus were on the rise—generalists capable of using tools, controlling fire, and adapting to a wider range of diets and habitats.

The specialist was outmaneuvered by the flexible thinker.

But extinction does not mean failure. Evolution is not a ladder with winners at the top. It is a sprawling, chaotic, creative force. And Paranthropus boisei was one of its masterpieces—a creature so well suited to its moment that it lasted over a million years. Few species can say the same.

Unraveling the Threads of Identity

What does Paranthropus boisei tell us about ourselves? In many ways, it shows how diverse our evolutionary family really was. It reminds us that there was never just one way to be human—or prehuman. Bipedalism, tool use, diet, brain size—these traits evolved in different combinations across species.

The very existence of Paranthropus boisei challenges the idea that brainpower alone determines success. Here was a hominin that survived not because it was the smartest, but because it was exquisitely adapted to its diet and environment. Its legacy is not in inventions or migration, but in the quiet, daily struggle to survive by chewing on what others could not.

And yet, its disappearance warns of the limits of specialization. When the world changes, those who can change with it endure. Those who cannot, fade.

It’s a lesson that echoes across evolutionary history—and perhaps, if we listen closely, into our future.

Discoveries That Brought It to Life

Since Mary Leakey’s 1959 discovery—initially dubbed “Zinj” and later classified as Paranthropus boisei—other fossils have helped flesh out the species’ story. Jawbones, teeth, cranial fragments, and postcranial remains have been found across East Africa.

The species’ name honors Charles Boise, a patron of the Leakey family’s work. Initially, it was given the genus name Zinjanthropus—meaning “East African man”—but it was later reclassified as a species of Paranthropus, a genus that includes other robust australopiths like Paranthropus robustus in South Africa and Paranthropus aethiopicus.

Together, these “robust australopithecines” represent a distinct evolutionary experiment—an offshoot that explored the limits of powerful jaws and hard foods.

Some of the most famous specimens include OH 5 (Olduvai Hominid 5), the original skull; the Peninj mandible from Tanzania, an almost complete jaw with molars intact; and KNM-ER 406, a well-preserved cranium from Kenya.

These fossils continue to inform our understanding of not just Paranthropus boisei, but of how evolution shaped the entire hominin landscape.

Imagining the World of Paranthropus

What was a day like for Paranthropus boisei?

Picture this: morning light spills across an East African riverbank. A small group of Paranthropus boisei—mostly females with young—move slowly among the reeds. They squat, dig with their hands, pull up roots, and chew, endlessly chew. The adults communicate in grunts and gestures. Their social bonds are simple, but strong. Males, larger and more solitary, keep a distance, sometimes joining briefly during mating seasons.

Predators are ever-present—lions, leopards, saber-toothed cats. They have no spears, no fire. They rely on vigilance, on numbers, and on the shelter of trees or rocky outcrops. Rain brings floods; drought brings hunger. There are no guarantees.

But in their simplicity lies a kind of grace. They are not striving to build monuments or conquer empires. They are simply trying to survive—to pass genes into the next generation, as every species does. And they succeed, for a long time.

Then one day, a child is born who will never find the same food, the same shelter, the same world. The lineage ends—not with a catastrophe, but with a whisper.

The Long Shadow of a Vanished Lineage

Today, we walk the Earth as the only surviving hominin. But we are not alone in spirit. Behind us trail shadows—long lines of ancestors and cousins whose bones rest in stone and soil. Paranthropus boisei is one of them.

It does not speak to us in words, but in fossils—in the curve of a jaw, the flare of a cheekbone, the wear on a molar. It tells us that the story of human evolution is richer and more complex than we once imagined.

It is not the direct ancestor of humanity. But it is part of our story.

A reminder that evolution does not move with intention, but with opportunity. A reminder that success can wear many faces, even ones that vanish in the end.

And most of all, a reminder that we, too, are just one experiment—an intelligent, tool-making, globe-spanning experiment—walking a path through time, never knowing exactly what lies ahead.