Beneath the stone layers of southern Germany, where limestone has locked away the shadows of a forgotten sea, a strange and tragic story has been revealed—one that took place over 150 million years ago, in the quiet, hostile waters of the Late Jurassic.

Somewhere in that vanished ocean, small silvery fish darted through the shallow lagoons of the Solnhofen archipelago. These were Tharsis, an extinct genus of ray-finned fish. Swift, sleek, and young—they were subadults, not yet fully grown—but their fate has become fossilized in stone. A new study by Dr. Martin Ebert and Dr. Martina Kölbl-Ebert, published in Scientific Reports, reveals that many of these ancient fish died not by the bite of predators, but by their own fatal mistake: trying to eat something they couldn’t swallow.

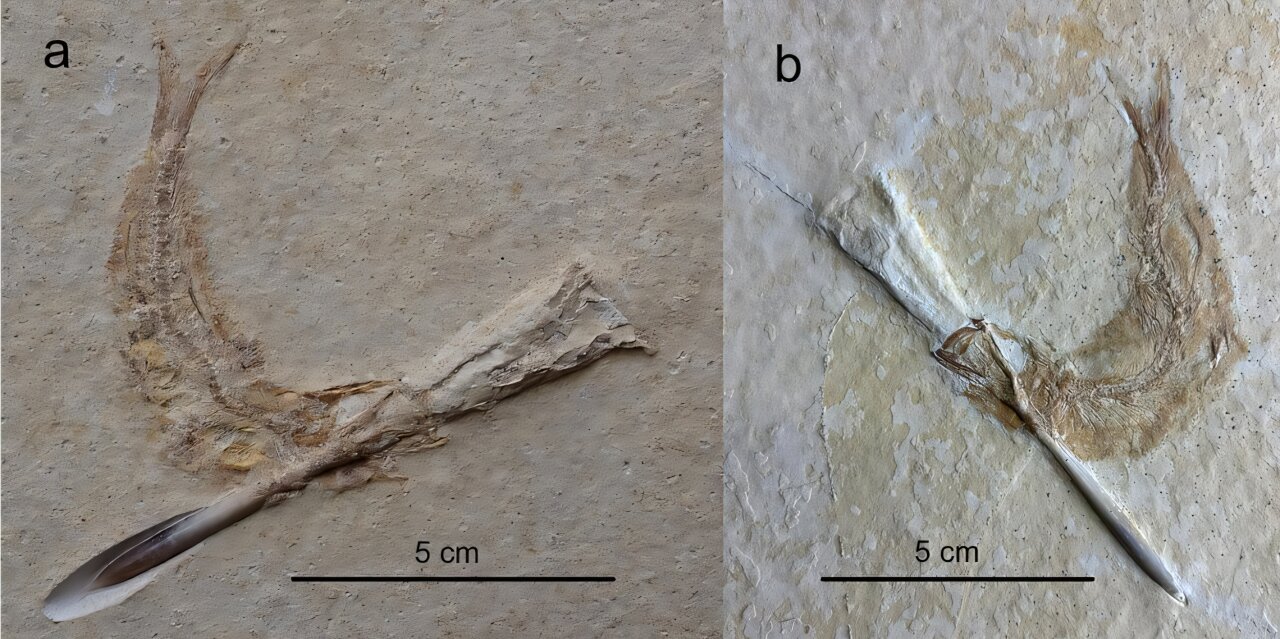

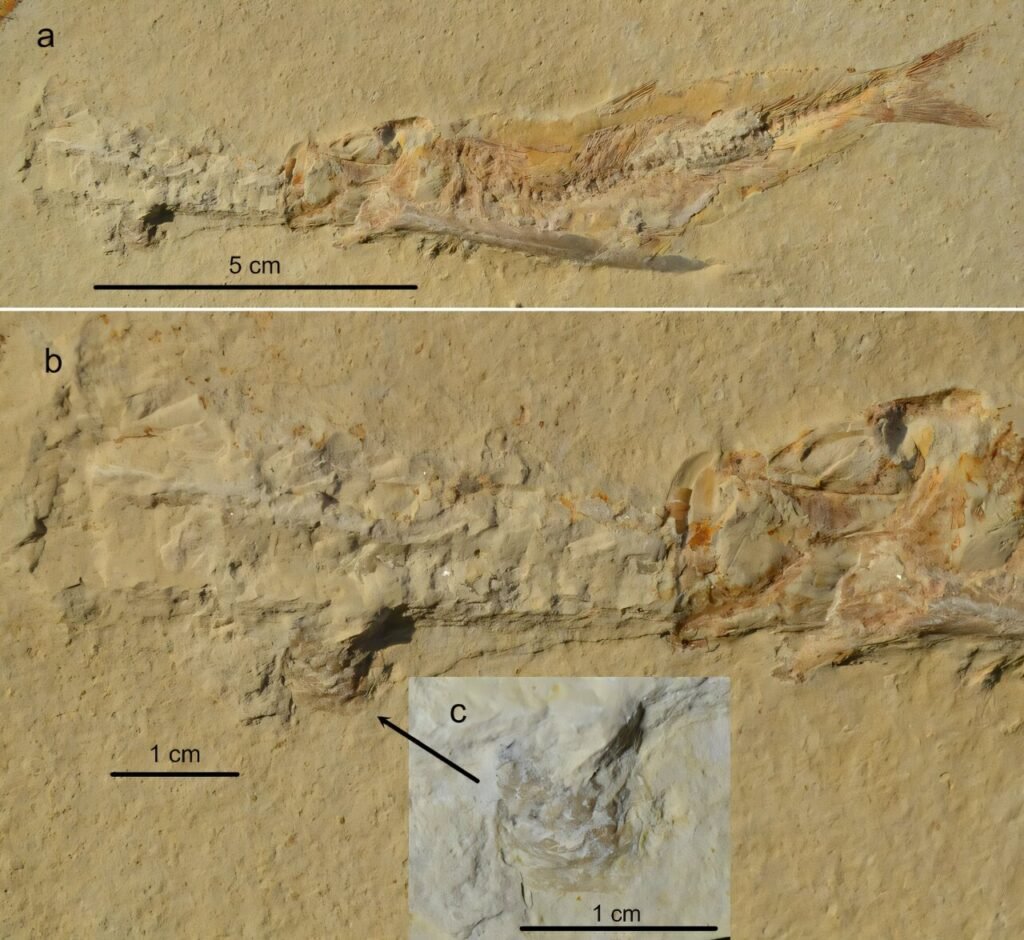

In fossil after fossil, these researchers found a peculiar sight—belemnites, the bullet-shaped remnants of squid-like cephalopods, lodged fatally in the throats of the Tharsis fish. In their final moments, these fish had been choking. On food. On instinct. On a decision that led to death.

A Graveyard of Beauty and Doom

The Solnhofen Limestone is world-renowned for its fossils—perfectly preserved ancient jellyfish, dragonflies with crystal-clear wings, ammonites spiraling like golden galaxies, and the legendary Archaeopteryx, the bird-like dinosaur that flew above them all. But this region wasn’t paradise. Far from it.

These basins were part of a shallow marine archipelago with high salinity and low oxygen levels, a difficult environment where life clung to narrow margins. The lagoon floors were nearly lifeless. Anything that sank to the bottom—be it fish or squid or driftwood—was quickly suffocated and preserved in fine-grained sediment, like a photograph sealed in stone.

Dr. Ebert, who personally examined more than 4,200 Tharsis specimens across museum collections, noticed something strange. Among the seemingly endless fossilized fish, some had their mouths agape in silent struggle. Lodged in their throats were the hard rostrums—the internal skeletons—of belemnites.

Why had these fish tried to eat such unusual prey?

Mistaking Death for Dinner

Belemnites were cephalopods, distant relatives of modern squids and cuttlefish. During the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, they roamed the open oceans. They were not common in the Solnhofen basins—in fact, only about 120 fossil belemnites have ever been found there, compared to over 15,000 fish fossils.

These cephalopods didn’t live in the lagoons. But they did die in the open sea, and their floating corpses sometimes drifted into the archipelago’s quiet waters. There, over days or weeks, their bodies were colonized by algae, bacteria, and possibly soft tissue decomposition—a process that may have transformed them into appealing “snack-like” objects for hungry Tharsis.

“From present-day experience, we know that such floating objects are quickly overgrown with algae and bacteria,” said Dr. Kölbl-Ebert. “Thus, for the fish, they smell and taste like food.”

Tharsis were micro-carnivores or visual zooplanktivores—they usually dined on tiny organisms, detritus, and possibly decaying matter. It’s likely they approached the algae-coated belemnite remains as they would any other food source.

But unlike soft plankton or decomposing tissue, the bullet-shaped belemnite rostrum was solid and unforgiving. The narrow tip could fit in the Tharsis’ mouth, but as the fish tried to swallow more, the rostrum’s increasing width made it impossible to finish the task. Unable to bite it off, or spit it out, the fish began to panic.

Death in the Throat

What followed was a slow, suffocating end. Like modern fish observed with large prey stuck in their throats, these Jurassic swimmers likely struggled for breath as their gills failed to draw enough oxygen. Some attempted to expel the belemnites through their gill slits—an act that may have torn delicate tissue and hastened death.

Within a few hours, their bodies would have lost the fight. They would sink into the oxygen-starved bottom of the lagoon. And there, time would stop. The fine Plattenkalk sediments would wrap around them, undisturbed by scavengers, freezing their final breathless moment for eternity.

It’s a tragic image: a young fish, reaching for a meal, misjudging the prey, and dying with its mouth full—not from a predator’s strike, but from the betrayal of its own instincts.

Overlooked Victims, Unseen Stories

The phenomenon had remained unnoticed for decades, despite the abundance of Tharsis fossils in museums. That’s partly because these fish are too common. With thousands of specimens, researchers typically focus only on the rare, beautifully preserved examples for taxonomic classification.

But Dr. Martin Ebert took a different approach. He looked at the masses. Through sheer perseverance—examining thousands of specimens, not just a few—he discovered the hidden pattern.

“Since Tharsis is so very common, taxonomists usually look only at a very few, exceptionally well-preserved specimens,” said Dr. Kölbl-Ebert. “Martin looks at so many specimens because he is doing statistics and is interested in ecology as well.”

It’s a reminder that even in well-trodden fossil beds, surprises still await those who look closely enough.

Ancient Lessons in Modern Times

What does a choking Jurassic fish have to teach us today? On the surface, it’s a simple case of mistaken identity—a fish misjudging its food. But deeper down, it’s a story about instinct gone awry, about survival in harsh environments, about the razor-thin line between life and death in ancient ecosystems.

It’s also a testament to the power of paleontology. Fossils aren’t just bones and impressions. They’re moments. Behaviors. Decisions. Mistakes. Stories. And sometimes, those stories are heartbreakingly familiar—even when told by a creature that vanished 150 million years ago.

In the silence of stone, a fish still gasps for breath. And in that silence, science finds its voice.

Reference: Ebert, M., Kölbl-Ebert, M. Jurassic fish choking on floating belemnites. Scientific Reports (2025). doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00163-7