Some 125,000 years ago, on the windswept plains of what is now Germany, a group of Neanderthals gathered by a fire near a shallow lake. Around them were bones—crushed, scorched, steaming. These ancient humans weren’t just gnawing on meat or scavenging scraps. They were cooking, boiling, and extracting something far more valuable than protein: fat.

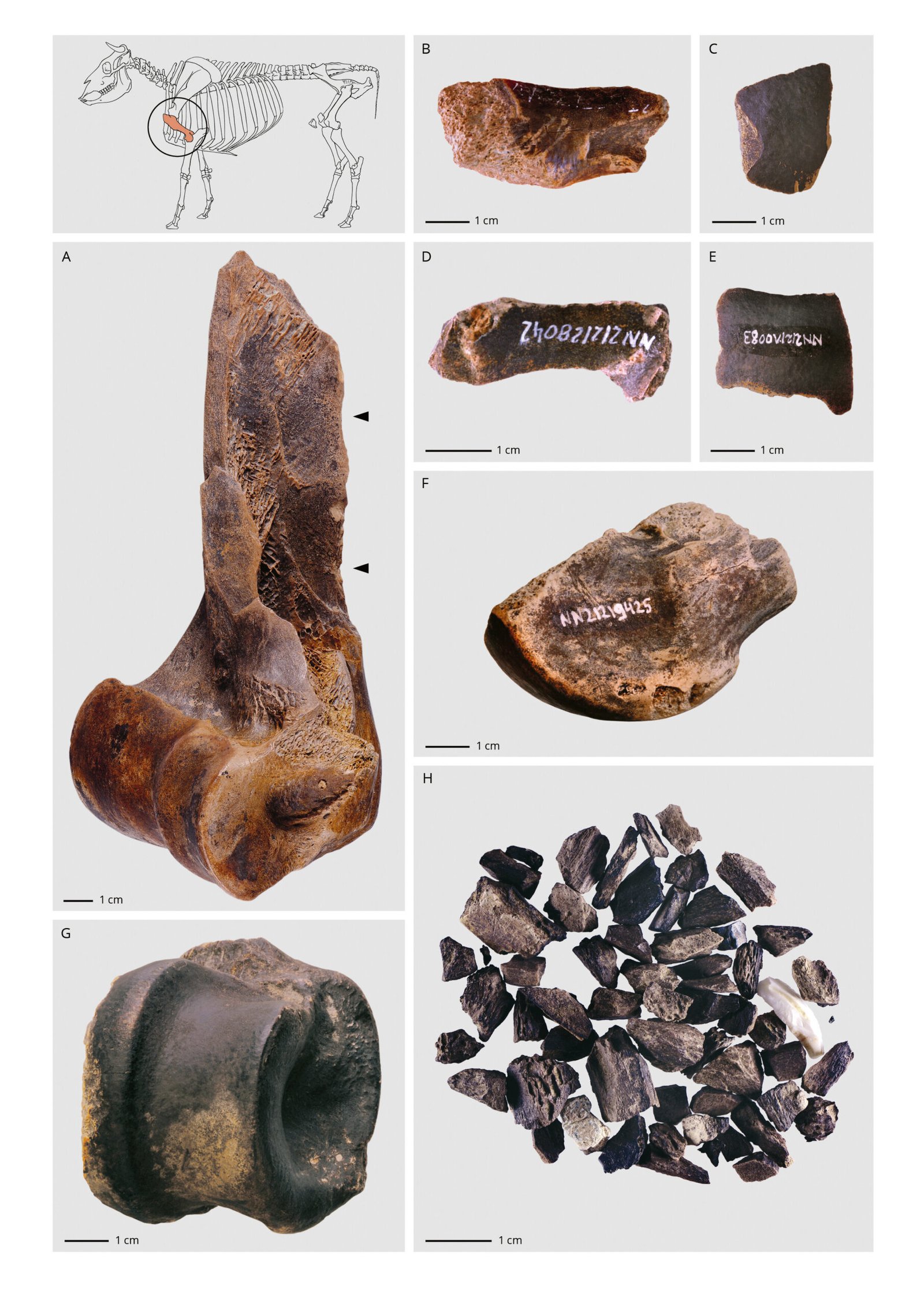

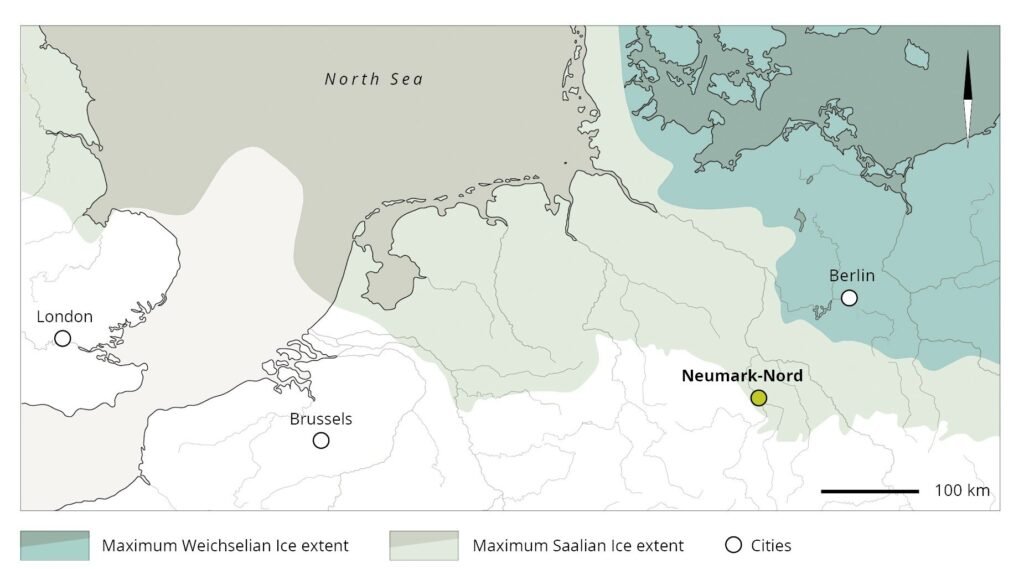

A groundbreaking new study published in Science Advances reveals stunning evidence that Neanderthals engaged in complex food processing techniques long before previously thought. At the Neumark-Nord archaeological site near Halle, Germany, researchers uncovered the remains of what they are calling a “fat factory”—a prehistoric kitchen where early humans purposefully crushed and heated bones to render fat, a critical and calorie-rich nutrient essential for their survival in harsh Ice Age environments.

This discovery doesn’t just push back the timeline of culinary innovation—it radically redefines our understanding of Neanderthal intelligence, resourcefulness, and adaptation.

The Protein Paradox of Prehistoric Life

For decades, scientists have known that Neanderthals and early Homo sapiens relied heavily on hunting large animals—bison, deer, horses—to meet their substantial caloric needs. But there was a catch. These animals provided ample protein, yet the human body can only process so much of it.

Research shows that excessive protein consumption—beyond about 1,200 calories per day—can overwhelm the liver, leading to a condition known as “rabbit starvation.” Named for the lean meat of rabbits, which lacks sufficient fat, this form of protein poisoning can lead to nausea, diarrhea, and ultimately death if not balanced with fats or carbohydrates.

For Neanderthals, who likely burned thousands of calories daily while hunting and surviving in cold climates, this limitation posed a serious nutritional problem—especially during winter and early spring, when carbohydrate-rich plants were scarce.

The answer? Bone fat.

Cracking Bones for Liquid Gold

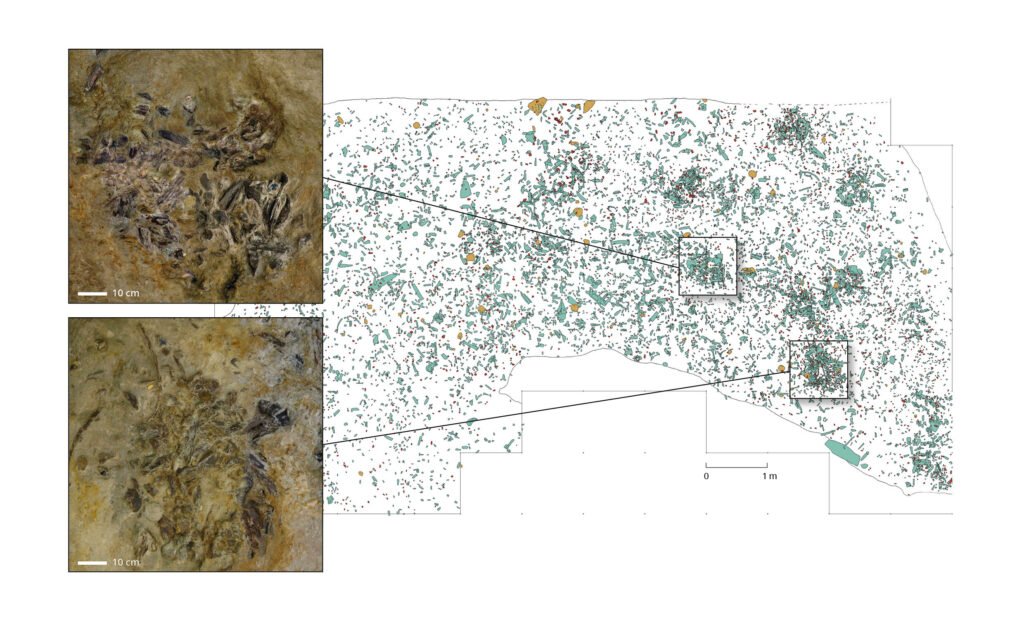

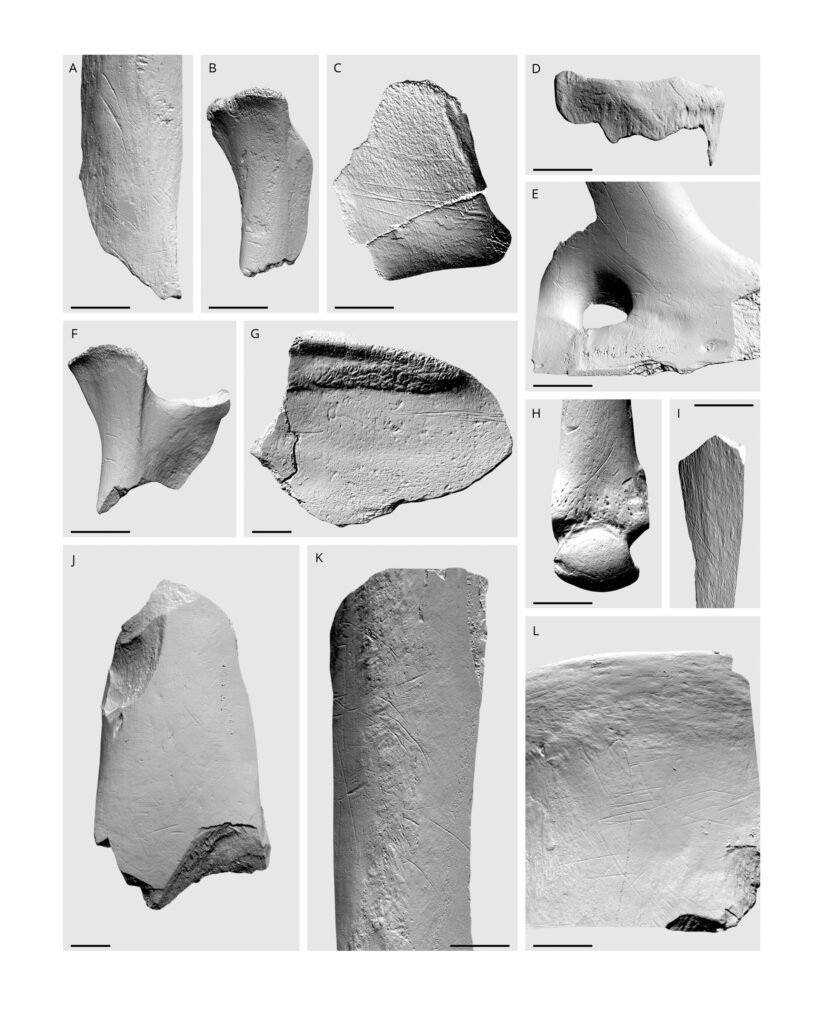

At Neumark-Nord, scientists uncovered the remains of at least 172 large animals, mainly red deer, aurochs (a now-extinct ancestor of cattle), and horses. But it wasn’t just the number of bones that amazed them—it was their condition. Many of the bones, particularly high-fat ones like femurs and jawbones, had been smashed into small fragments. These pieces showed signs of intentional heating and were found clustered near charcoal and water sources.

“This wasn’t random butchering,” says lead archaeologist Dr. Sabine Gaudzinski-Windheuser. “This was systematic. These Neanderthals were processing bones to extract fat, likely by boiling them. It’s the earliest evidence of such sophisticated food processing we’ve ever found.”

Previously, the oldest confirmed evidence of bone fat rendering came from about 28,000 years ago—almost 100,000 years after the Neumark-Nord activity. That older evidence was attributed to early modern humans. Now, it seems Neanderthals were already using similar techniques long before.

Rendering the Unseen

While no actual pots or containers have been recovered at the site, researchers believe the Neanderthals used perishable materials—perhaps birch bark bowls or hollowed-out animal hides—to boil crushed bones and collect the fat. When heated, marrow and bone grease rise to the surface of water and can be skimmed off and stored. In cold climates, such rendered fat becomes solid and stable, lasting weeks or even months—a prehistoric superfood.

What’s especially compelling is the selectivity of the bone remains. The majority of fragments came from fat-rich bones. By contrast, bones with low-fat content—like those from feet—were far less common in the processing areas. This pattern suggests not only nutritional knowledge but intentional food engineering.

“These people weren’t just surviving,” says Dr. Gaudzinski-Windheuser. “They were planning. They were extracting resources with skill and strategy.”

A Different Kind of Neanderthal

The popular image of Neanderthals has long been one of brutish, unsophisticated survivalists—strong but dim-witted, scraping by on raw meat and instinct. But discoveries like this challenge that outdated stereotype.

At the “fat factory” of Neumark-Nord, we see a different kind of Neanderthal: one capable of foresight, culinary innovation, and metabolic calculation. These ancient people understood their own biology—whether consciously or intuitively. They knew that protein alone couldn’t sustain them and that bone grease was the answer. They were problem solvers, not just predators.

The ability to process bone fat also points to an understanding of delayed gratification. Bone grease extraction takes time and effort. It requires planning, fire maintenance, tools, and probably group cooperation. It’s not something you do unless you expect a valuable payoff.

Questions That Still Simmer

Despite the breakthrough, some questions remain. How long did Neanderthals use this site? Was it a seasonal processing station or a long-term hub of activity? Did they store the rendered fat for later use? And how widespread were these practices among other Neanderthal groups?

Because the site lacks preserved containers, some conclusions remain speculative. But the circumstantial evidence—bones, fire remains, water access, selective processing—paints a compelling picture.

Moreover, this study raises the possibility that other similar sites exist but have gone unrecognized. If bone grease rendering was common among Neanderthals, we may need to rewrite entire chapters of prehistoric human behavior and innovation.

A Greasy Window Into the Past

In the grand saga of human evolution, moments of ingenuity often go uncelebrated. The invention of fire, the sharpening of a stone tool, the stitching of animal hides—each one nudged our ancestors closer to survival. Now, we must add another: the rendering of fat from bone.

It’s a greasy, smoky, laborious process. But 125,000 years ago, it may have been the difference between life and death.

As the embers died down near the lakeshore and the Neanderthals stored their precious fat for the days ahead, they probably didn’t think of themselves as innovators. They were just doing what it took to make it through another cold season.

But in doing so, they left behind a clue—a charred shard of bone, a puzzle piece—that would help modern scientists see them not as shadows in a cave, but as masters of survival. Strategic, capable, and surprisingly sophisticated.

In the echoes of their fire pits, we can hear something ancient but familiar: the human instinct to adapt, to innovate, and to endure.

Reference: Lutz Kindler et al, Large-scale processing of within-bone nutrients by Neanderthals, 125,000 years ago, Science Advances (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adv1257