High in the Blue Mountains of southeastern Australia, nestled among towering cliffs and eucalypt forests, a shallow cave known as Dargan Shelter has been keeping an ancient secret. Now, after thousands of years, it has spoken—through fire pits, stone tools, and chemical clues buried deep in the earth.

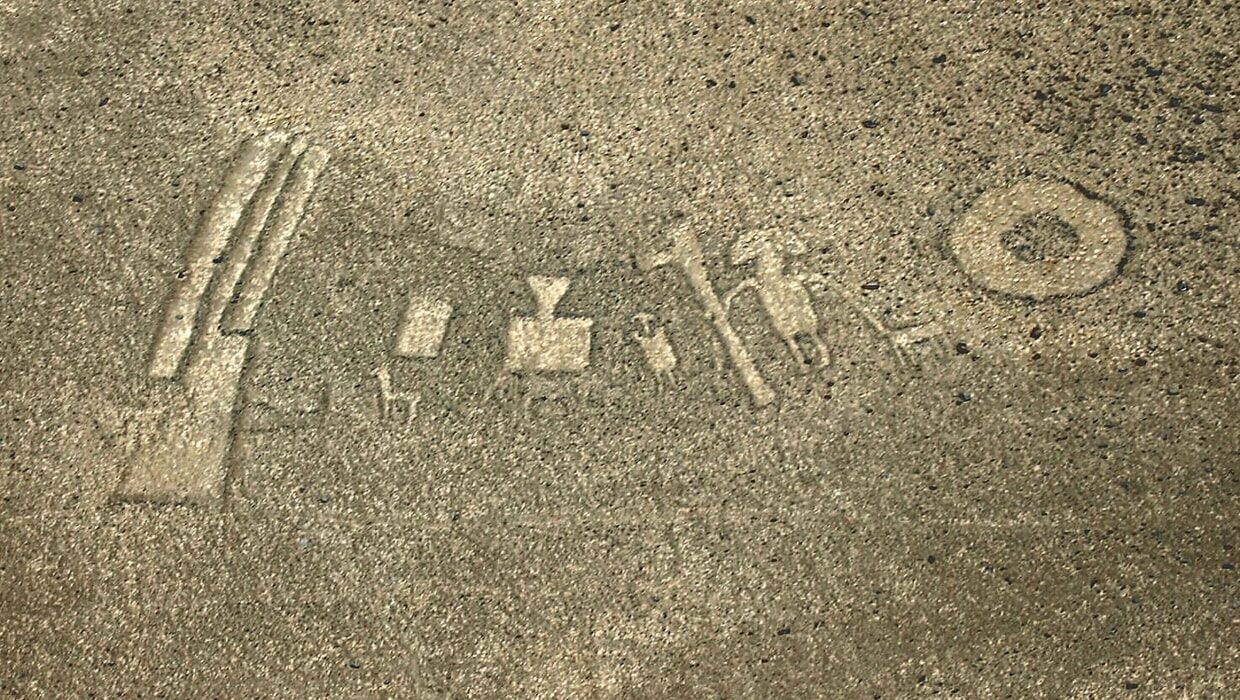

In a groundbreaking study published in Nature Human Behaviour, a team of archaeologists from the Australian Museum, the University of Sydney, and the Australian National University (ANU), working in close partnership with First Nations community members, have unearthed nearly 700 stone artifacts from the cave. These tools—painstakingly preserved in ancient sediment—trace a continuous human presence through time, stretching from the height of the last ice age to the recent past.

Their discovery not only upends long-held assumptions about Australia’s human history but also affirms the deep cultural knowledge that First Nations custodians have carried for millennia.

A Cold, Treeless World—and the People Who Lived There

Around 20,000 years ago, the world was gripped by an icy breath. Glaciers sprawled across continents, sea levels dropped, and in Australia’s southeastern highlands, alpine winds howled across barren, treeless peaks. Scientists long believed these frozen altitudes were too harsh, too unforgiving for human life.

But deep within Dargan Shelter—perched 1,073 meters above sea level—archaeologists found something astonishing. Amid blackened hearths and sharp stone flakes, they uncovered a vibrant record of human activity dating back to this glacial period.

“This changes everything,” said Dr. Amy Mosig Way, lead author of the study and archaeologist with the Australian Museum and University of Sydney. “Until now, we thought the Australian high country was uninhabitable during the last ice age. Yet here we have clear evidence of people not only surviving, but actively moving through and adapting to this environment.”

Their presence during a time when the upper Blue Mountains were seasonally frozen and stripped of forest reveals a resilience and adaptability that echoes across millennia.

Guided by Ancestors, Informed by Science

This discovery is not just about artifacts or stone. It’s about people—and it began with a story.

Wayne Brennan, a Gomeroi knowledge holder and rock art specialist, first proposed exploring Dargan Shelter. As a mentor in First Nations archaeology at the University of Sydney, Brennan envisioned a project where science and culture walked together—honoring the voices of those whose ancestors once knelt around ancient fires beneath the cave’s rocky ceiling.

Brennan, along with researchers Dr. Way and Associate Professor Duncan Wright from ANU, worked in close collaboration with custodians from the Dharug, Wiradjuri, Dharawal, Gomeroi, Wonnarua, and Ngunnawal nations. These are people whose families trace unbroken connections to the Blue Mountains landscape.

“Dargan Shelter is not a random discovery,” Brennan explained. “Our people have always known this place. We knew the cave was there. It’s part of our living story.”

That story is written not just in memory, but in stone.

The Tools That Tell Time

The team recovered 693 stone artifacts in total—tools used for cutting, scraping, and crafting—each one a silent witness to lives lived under extreme conditions. Through radiocarbon dating and analysis of stratified layers, scientists created a timeline of human activity stretching over 20,000 years.

What they found was more than momentary occupation—it was repetition. Hearths, scattered stone fragments, and chemical residues painted a picture of people returning again and again, generation after generation, to this elevated refuge.

Professor Philip Piper, co-author from ANU, noted the remarkable preservation of the site. “The depositional sequence was pristine,” he said. “It allowed us to construct a detailed chronology—something rarely possible in highland archaeological sites.”

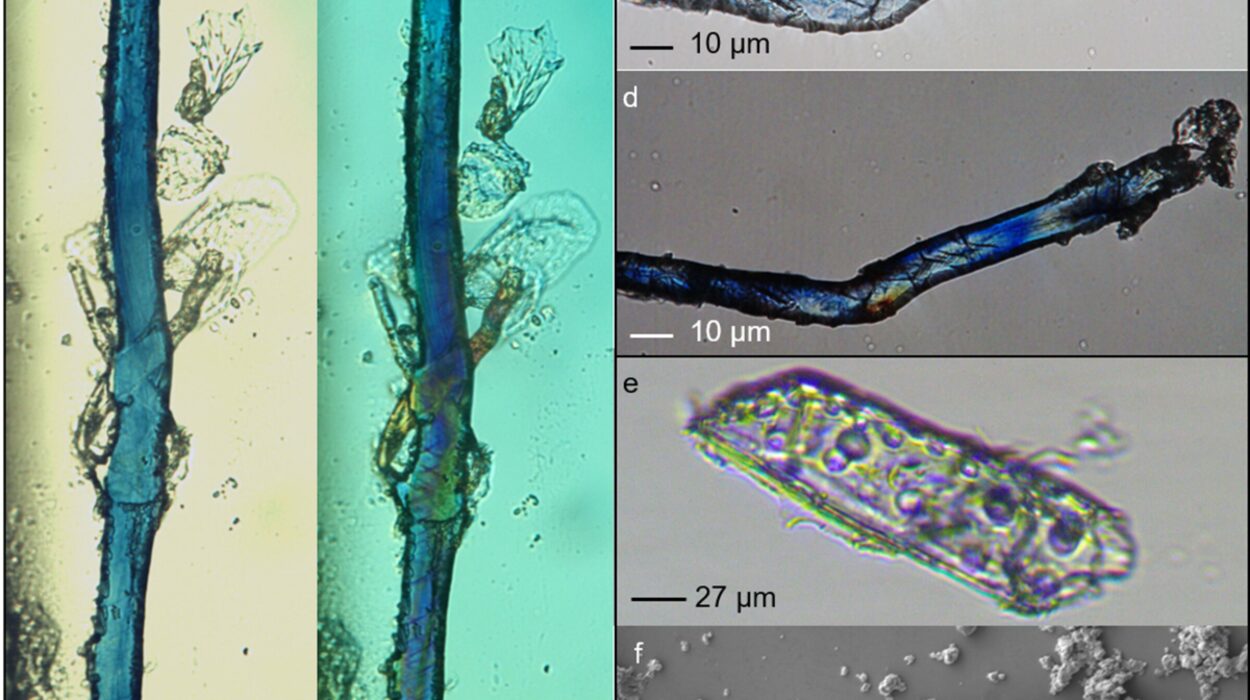

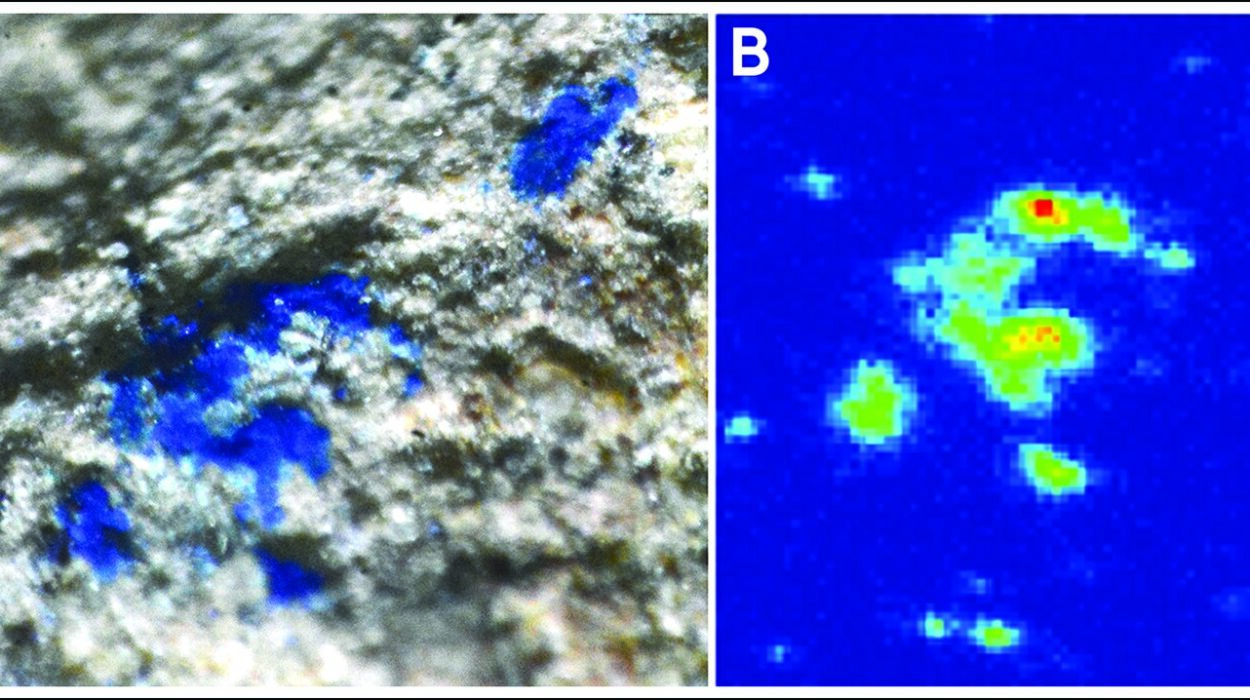

Emily Nutman, Ph.D. candidate at ANU, led a geochemical analysis of the artifacts. Her work traced the origin of some of the stones to regions far beyond the cave—such as the Hunter Valley and the Jenolan Caves area—indicating that ancient people traveled long distances across rugged terrain to reach this high mountain shelter.

“These weren’t isolated bands,” she explained. “They were mobile, connected, and knowledgeable about the land. Even in the ice age, people were navigating significant distances to share knowledge, resources, and culture.”

A Shelter of Memory and Identity

For Leanne Watson Redpath and Erin Wilkins, Dharug women and co-authors on the study, the findings confirm what their communities have always known.

“Our people have walked, lived, and thrived in the Blue Mountains for thousands of years,” said Watson Redpath. “This cave is more than just an archaeological site—it’s a living piece of our identity. A place of gathering, storytelling, and survival.”

Wilkins emphasized the importance of safeguarding such places, which are often overlooked in environmental protections.

“The Blue Mountains is a UNESCO World Heritage site for its natural beauty and biodiversity,” she said. “But our cultural heritage has no such protections. Dargan Shelter shows just how deep our roots go. It’s vital that we preserve this legacy—not just for First Nations people, but for all Australians.”

For now, the exact location of Dargan Shelter remains undisclosed, to protect it from disturbance and honor its cultural significance.

Rewriting the Map of Human Occupation

The significance of this discovery stretches far beyond the ridgelines of New South Wales. Globally, scientists have debated whether glacial terrains posed impassable barriers to early humans. In Europe and Asia, archaeological evidence has slowly emerged to suggest that humans not only ventured into icy highlands—they thrived there.

Now, Australia joins that conversation.

“This research aligns us with global data,” said Dr. Way. “It proves that people in Australia were not confined to warm coastal refuges. They were in the mountains, in the cold, adapting to periglacial environments with incredible skill.”

Associate Professor Wright sees the find as part of a broader revision of early human behavior.

“Dargan Shelter is a missing puzzle piece,” he said. “It offers rare insights into southeastern Australia’s early occupation—a region still underrepresented in the archaeological record, despite being the country’s most densely populated area today.”

A Future Rooted in the Past

As scientists carefully brush away layers of time, Dargan Shelter continues to offer its quiet revelations—one stone tool, one hearth, one soil sample at a time.

But for the First Nations communities who have long cared for this land, the past has never been buried.

“This place is alive in our memories,” said Brennan. “And through projects like this—where science respects culture—we can ensure those memories are passed on. Not just as data in a paper, but as something living. Something that teaches us how to care for each other and for the land.”

In a country still coming to terms with its deep time history, Dargan Shelter stands as a powerful reminder: that even in the harshest times, human creativity, endurance, and connection to place have always endured.

It’s not just a cave in the mountains. It’s a testament. A story carved in stone, waiting patiently for us to listen.

Reference: Amy M. Way et al, The earliest evidence of high-elevation ice age occupation in Australia, Nature Human Behaviour (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41562-025-02180-y