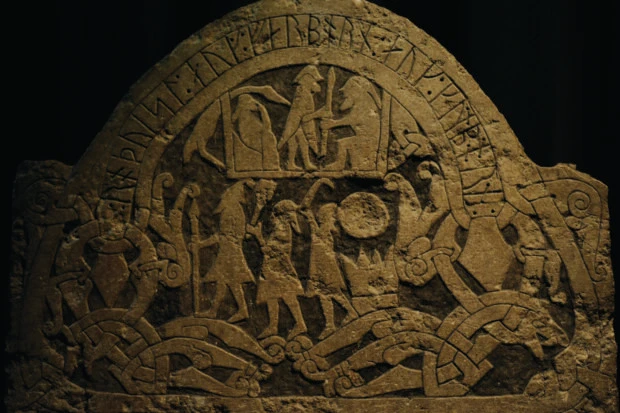

To step into the world of the Vikings is to enter a landscape where the natural and supernatural were inseparably intertwined. The Norse people who lived in Scandinavia during the Viking Age (roughly 750–1050 CE) did not view their gods as distant abstractions or invisible forces. Their deities walked among them in story and ritual, shaping the cycles of war and peace, the rhythms of harvest and famine, and the destinies of both kings and commoners.

For the Vikings, religion was not something confined to temples or priests. It was woven into everyday life—into the building of ships, the offering of sacrifices, the oaths sworn in blood, and the dreams of warriors who longed to die bravely so they might feast eternally in Odin’s hall. Viking religion was a living faith, grounded in myth and ritual, filled with awe, dread, and wonder at the mysteries of existence.

At its heart, Viking spirituality revolved around a pantheon of gods and goddesses, forces of creation and destruction, fate and freedom. It also revolved around deep beliefs about the afterlife—what happened when the soul departed, where it might go, and how one’s deeds in life could shape that eternal journey. Together, these beliefs gave the Vikings a worldview that was both profoundly human and fiercely cosmic, a religion where honor mattered as much as survival, and where even the gods themselves were fated to face their own doom.

The Norse Pantheon: Gods Among Men

The Viking gods were not all-powerful, perfect beings. Unlike the single, almighty deity of Christianity, which was spreading through Europe during the Viking Age, the Norse gods were many, each with their own personalities, strengths, flaws, and rivalries. They were anthropomorphic—humanlike in form—but lived in realms beyond the mortal world, influencing both fate and the natural order.

The pantheon was divided into two main families: the Aesir and the Vanir. The Aesir were the gods of power, war, and sovereignty, while the Vanir were associated with fertility, prosperity, and the cycles of nature. Though they once warred with each other, the Aesir and Vanir eventually made peace, exchanging hostages and creating a shared divine order.

Odin: The Allfather

Odin, the chief of the Aesir, was not a simple war god but a complex, enigmatic figure. Known as the Allfather, he was the ruler of Asgard, but he was also a wanderer who sacrificed much in his pursuit of wisdom. He gave one of his eyes at the Well of Mimir to gain knowledge and hung himself on the world tree Yggdrasil for nine days and nights to discover the runes, the magical alphabet of the cosmos.

Odin was associated with war, but not in the sense of brute strength—that was Thor’s domain. Instead, he was a god of strategy, cunning, and the frenzy of battle. He was also a god of poetry, magic, and prophecy, inspiring skalds (poets) as well as warriors. Yet Odin was not always benevolent; he could be deceitful, ruthless, and manipulative, willing to sacrifice anything and anyone in pursuit of knowledge and power.

Thor: The Defender of Gods and Men

If Odin was the wise and mysterious Allfather, Thor was the thunderous protector. With his mighty hammer Mjölnir, Thor defended both gods and humans from the giants, the chaotic forces that threatened cosmic order. He was associated with storms, strength, fertility, and protection. Farmers prayed to him for good harvests, and warriors invoked his strength in battle.

Thor was also the most beloved of the gods among the common people. His hammer was a symbol of blessing, used to sanctify marriages, births, and funerals. Unlike Odin, whose wisdom could be dark and foreboding, Thor embodied straightforward courage, loyalty, and reliability.

Freyja: The Goddess of Love and War

Freyja, a member of the Vanir, embodied the complexity of Norse religion. She was a goddess of love, beauty, and fertility, but also of war and death. Freyja had her own hall, Folkvangr, where she received half of those slain in battle—the other half went to Odin’s Valhalla. This duality made her one of the most powerful and influential deities in Norse belief.

She was also associated with magic, particularly a form called seiðr, a prophetic and shamanic practice. Freyja’s mastery of seiðr was so great that even Odin sought her guidance. She was a goddess of passion and desire, but also of power and destiny, embodying both nurturing and destructive aspects of life.

Loki: The Trickster and Chaos-Bringer

Loki occupied a unique place in Viking religion. He was not worshiped like Odin or Thor, but he played a central role in myth. A shapeshifter and trickster, Loki could help the gods one moment and betray them the next. He was clever, unpredictable, and often the source of both trouble and solutions.

Yet Loki’s mischief had a darker side. He fathered monstrous offspring, including the wolf Fenrir, the serpent Jörmungandr, and Hel, the ruler of the underworld. His role in the death of the beloved god Baldr set in motion the events that would lead to Ragnarök, the end of the world.

Loki represented the chaotic, uncontrollable forces of existence—the reminder that even in a world of gods, nothing was permanent or entirely safe.

Other Deities and Beings

The Norse pantheon was vast, including not only the well-known figures of Odin, Thor, Freyja, and Loki, but also gods and goddesses such as Frigg (Odin’s wife and goddess of foresight), Tyr (the one-handed god of law and justice), Freyr (god of fertility and prosperity), and Heimdall (the watchman of the gods).

Beyond the gods were the giants (jötnar), beings of immense power who were not always evil but represented the primal, chaotic forces of nature. There were also elves, dwarves, spirits, and landvættir (land-spirits), all part of the Vikings’ spiritual landscape.

Rituals, Worship, and Sacrifice

The Vikings did not have a single holy book or rigid doctrine. Their religion was passed down through oral tradition, poetry, and ritual. Worship took place in sacred groves, stone circles, and sometimes in specially constructed temples called hofs. But just as often, rituals were held in homes, fields, or open landscapes where the presence of the divine was felt.

Sacrifices, known as blót, were central to Viking worship. These offerings could include food, weapons, jewelry, or animals. In rare cases, historical sources suggest that humans were also sacrificed, especially in times of crisis, though such practices remain debated among scholars. The purpose of sacrifice was to maintain good relations with the gods, to seek blessings, and to ensure fertility, prosperity, and victory.

Feasting and drinking were also important parts of ritual, reinforcing community bonds while honoring the gods. Skalds recited poems and sagas, bringing the myths of the gods to life and connecting the human community to the divine.

The Afterlife: Where Do Souls Go?

One of the most fascinating aspects of Viking religion was their belief in the afterlife. Unlike many other cultures, the Norse did not envision a single destination for the dead. Instead, there were multiple realms where souls could go, depending on the manner of death, the favor of the gods, and perhaps even chance.

Valhalla: The Hall of the Slain

The most famous Viking afterlife is Valhalla, Odin’s hall in Asgard. Those who died bravely in battle were chosen by Odin’s valkyries, supernatural maidens who swept across the battlefield to carry the chosen warriors to their eternal reward.

In Valhalla, these warriors, known as the einherjar, feasted on endless supplies of meat and mead, and trained for the ultimate battle of Ragnarök. It was not a place of rest but of preparation, a warrior’s paradise where the bravest would stand beside Odin at the end of the world.

Folkvangr: Freyja’s Field

Equally important, though less widely remembered, was Folkvangr, the hall of the goddess Freyja. Here she welcomed half of those who died in battle, suggesting that even in war, death was not the sole domain of Odin. Folkvangr may have been seen as a more peaceful counterpart to Valhalla, a place of honor without the endless cycle of training for doom.

Hel: The Realm of the Dead

Not all souls died in battle. Those who succumbed to illness, old age, or misfortune often went to Hel, a realm ruled by Loki’s daughter of the same name. Hel was not a place of torment like the Christian Hell; rather, it was a cold, shadowy world where the dead existed in a kind of neutral state.

Hel was sometimes depicted as a place of dreariness, but not necessarily of punishment. In fact, some sagas describe noble figures going to Hel peacefully, suggesting that it was an ordinary part of the afterlife rather than a dishonorable fate.

Other Afterlife Realms

The Norse afterlife was more complex still. Sailors, for example, might go to the realm of Rán, the sea goddess, if they drowned. Some traditions spoke of reincarnation within families, where souls returned through newborn children. The multiplicity of afterlife destinations reflects the Vikings’ view of a cosmos filled with many powers and possibilities, where death was not a single gate but a branching path.

Fate and Destiny: The Role of the Norns

Underlying Viking beliefs in gods and afterlife was a profound sense of fate. The Norse believed in the Norns, three mysterious female beings who wove the threads of destiny at the roots of the world tree, Yggdrasil. Even the gods themselves were bound by fate, powerless to escape what had been woven.

This belief gave Viking religion a somber but resolute tone. Bravery in battle was not just admired but necessary, because death was inevitable and predetermined. The true measure of a person was not whether they lived or died, but how they faced the destiny given to them.

Ragnarök: The Doom of the Gods

Perhaps the most striking feature of Viking religion was its vision of the end times: Ragnarök, the “Twilight of the Gods.” Unlike religions that promised eternal stability or a final triumph of good over evil, Norse mythology foretold an apocalyptic battle in which even the gods would perish.

At Ragnarök, Loki and his monstrous children would break free. Fenrir would devour Odin, Jörmungandr would rise from the sea to fight Thor, and the fire-giant Surtr would set the world ablaze. The sun and moon would be swallowed by wolves, and the world as it was known would collapse into chaos.

Yet Ragnarök was not the end of everything. From the ashes, a new world would rise—green, fertile, and renewed. A few gods and humans would survive, suggesting a cycle of destruction and rebirth rather than final annihilation.

For the Vikings, this myth was not despairing but empowering. If even the gods could not escape fate, then courage, honor, and loyalty became the highest virtues. Life was fleeting, but deeds echoed in memory, and death was but one stage in the eternal cycle.

The Transition to Christianity

By the end of the Viking Age, Norse religion began to give way to Christianity. Kings such as Olaf Tryggvason and Olaf Haraldsson in Norway, and Harald Bluetooth in Denmark, promoted the new faith, sometimes peacefully, often by force. By the 12th century, Scandinavia was largely Christianized, though many Norse traditions persisted, blending with Christian beliefs in a cultural fusion.

The myths of Odin, Thor, and Freyja did not vanish; they were recorded by Christian scholars like Snorri Sturluson, whose Prose Edda preserved much of what we know today. These myths lived on in folklore, literature, and later in modern popular culture, from Wagner’s operas to Marvel comics.

Conclusion: A Faith of Courage and Wonder

Viking religion was not simply about gods and rituals. It was a worldview that embraced the beauty and brutality of existence, where even divine beings were mortal and destiny could not be escaped. It was a religion that valued bravery, loyalty, and honor, but also recognized the power of love, fertility, and magic.

The afterlife was not a single paradise or punishment, but a reflection of the many paths of life itself—warriors in Valhalla, the peaceful in Folkvangr, the ordinary in Hel, and the drowned in the arms of Rán. Fate was inexorable, yet how one lived and died mattered profoundly.

In studying Viking religion, we glimpse not only the spiritual life of a people long past but also universal human questions: How do we face death? How do we live honorably? How do we find meaning in a world where even gods must fall?

For the Vikings, the answer lay in courage, in loyalty, and in reverence for the mysteries of the cosmos. Their gods may have been destined to perish, but their stories—and the fierce spirit behind them—live on, eternal as the sagas sung by the skalds.