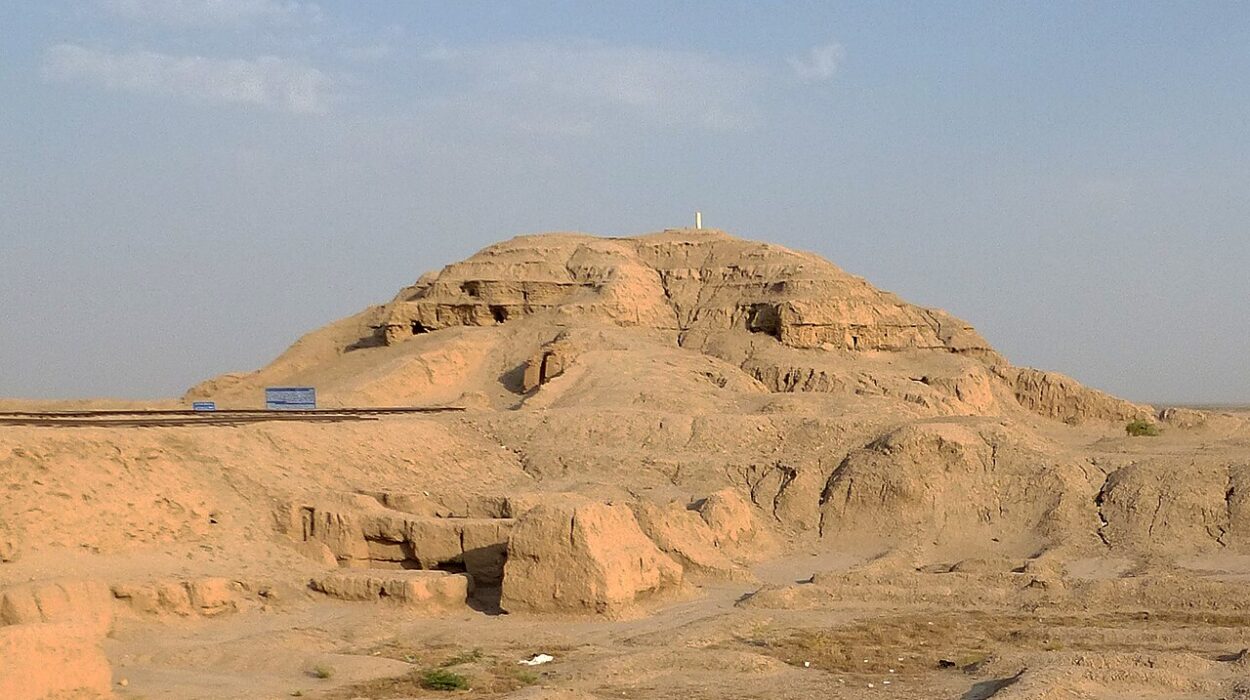

In the barren coastal deserts of Peru, where the parched earth meets the roaring Pacific, the ancient city of Vichama once flourished. For centuries, archaeologists have puzzled over how its people thrived in such an unforgiving environment — and whether the bounty of the sea or the fruits of the land fueled their survival.

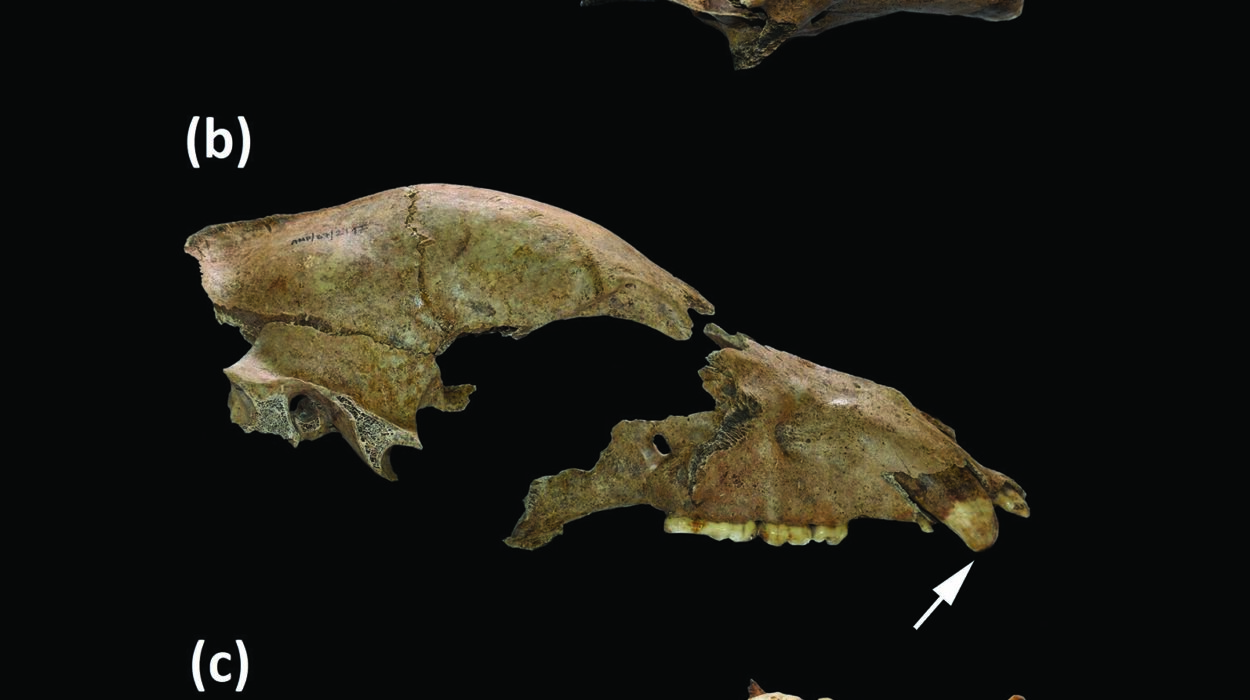

Now, a groundbreaking study led by Dr. Luis Pezo-Lanfranco has brought us closer to the answer. Through stable isotope analysis of the remains of 38 individuals who lived in Vichama between 1800 BCE and 1300 CE, researchers have reconstructed a vivid picture of their diets. The findings, published in Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology, reveal that despite living just 1.5 kilometers from the Pacific Ocean — one of the most biologically productive marine ecosystems on Earth — the people of Vichama relied far more on farming than fishing.

Farming Against the Odds

The results challenge the assumption that the ocean was the primary lifeline for ancient coastal communities. Instead, the data shows that during the earliest period of occupation — the Early Formative-1 phase (1800–1500 BCE) — residents of Vichama derived roughly three-quarters of their calories from C3 plants, such as beans, chilies, fruits, tubers, and roots. Fish and other marine resources made up less than a quarter of the diet.

Even more surprising, C4 plants like maize were a minor dietary component, accounting for under 10% of consumption, despite the valley’s potential for corn cultivation. The reason, Dr. Pezo-Lanfranco explains, may lie in the unpredictability of the region’s climate.

“Theoretically, the valley is suitable for maize cultivation; however, local farmers have traditionally focused on other crops,” he says. “Maize requires a consistent water supply, and during this period, climatic instability made it a risky investment. Communities may have relied instead on more resilient crops such as cucurbits and tubers.”

While maize had already been cultivated elsewhere along the Peruvian coast — including at sites like Caral — it may have been reserved for ceremonial use in Vichama rather than daily sustenance.

A Civilization Shaped by Climate

The Andean coast has long been a stage for dramatic environmental fluctuations. Changes in sea surface temperature, rainfall patterns, and the cyclical chaos of El Niño events could make or break harvests and fishing seasons. Around 4000 BCE, some of the earliest irrigation systems in the Americas emerged in this region, allowing farmers to tame the desert and coax crops from the sandy soil. By 3000 BCE, agriculture had overtaken fishing as the economic engine of coastal societies.

Vichama’s story fits neatly into this larger arc. In its earliest centuries, the city experienced a burst of monumental construction, becoming a key player in the lower Huaura Valley’s network of settlements. Even so, its farmers seem to have pursued a cautious, climate-sensitive approach to cultivation, choosing reliability over risk.

Adapting Over the Millennia

Fast-forward nearly 3,000 years to the Late Intermediate Period (1000–1300 CE), and the isotope evidence paints a slightly different picture. Cooler sea surface temperatures boosted marine productivity, making fish a more attractive option. While C3 plants still formed the bulk of the diet, marine resources became more prominent, showing that Vichama’s people adjusted their subsistence strategies to fit changing environmental conditions.

This opportunistic flexibility — intensifying either farming or fishing depending on climate patterns — may have been the key to the city’s resilience over centuries.

Looking Beyond the Plate

Dr. Pezo-Lanfranco’s team isn’t stopping at dietary reconstruction. They’re now turning their attention to plant micro-remains in dental calculus, stress markers in bones, and pollen analysis to better understand how environmental pressures shaped daily life.

One question looms large: why did regional power shift from Caral to Vichama? The researchers suspect the so-called “4.2 ka Event” — a period of global climate disruption around 2200 BCE — may have played a role. They’re also investigating long-distance mobility and trade. Exotic artifacts from the Amazon suggest connections spanning 300 kilometers eastward, hinting at vibrant exchange networks crisscrossing the Andes and rainforest.

Rethinking the Origins of Andean Civilization

The study’s findings have profound implications for our understanding of early Central Andean societies. Far from being passive recipients of environmental bounty, the people of Vichama were active strategists, navigating the delicate balance between sea and land in a region where both could be fickle.

By showing that farming — not fishing — was the foundation of their survival, the research rewrites a key chapter in Andean prehistory and reminds us of the adaptability that has always been at the heart of human resilience.

As Dr. Pezo-Lanfranco notes, “Vichama’s people weren’t just living in their environment — they were constantly negotiating with it. That negotiation shaped who they were, and ultimately, the civilization they built.”

More information: Luis Pezo-Lanfranco et al, Refining dietary shifts linked to climate oscillations in the Central Andes: stable isotope evidence from Vichama (1800–1500 BCE), Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology (2025). DOI: 10.3389/fearc.2025.1611071