In 1965, Yale University unveiled what it claimed was the most astonishing medieval artifact ever discovered: a world map from the mid-15th century that appeared to show part of North America, specifically “Vinland,” nearly fifty years before Columbus’s first voyage. If authentic, this map—the so-called Vinland Map—would rewrite history. It would provide tangible, visual proof that Norse explorers had not only reached North America, as sagas suggested, but that knowledge of their voyages had circulated in Europe well before the Age of Discovery.

The excitement was electric. Newspapers declared it a revolutionary find. Scholars debated whether this was the single most important map in Western history. Yale published a lavish facsimile edition, and the world’s eyes turned to the small, faded parchment that seemed to hold the power to challenge the Columbus narrative entrenched in textbooks.

But almost as soon as the fanfare began, doubts crept in. Was the map truly a product of the 15th century, or was it a clever modern forgery designed to thrill, deceive, and unsettle? Over the next half century, the Vinland Map became the center of one of the most contentious debates in the history of cartography, archaeology, and medieval studies. It enthralled believers, embittered skeptics, and ultimately forced the academic world to confront the messy business of evidence, authenticity, and human longing for historical validation.

The Map’s Appearance

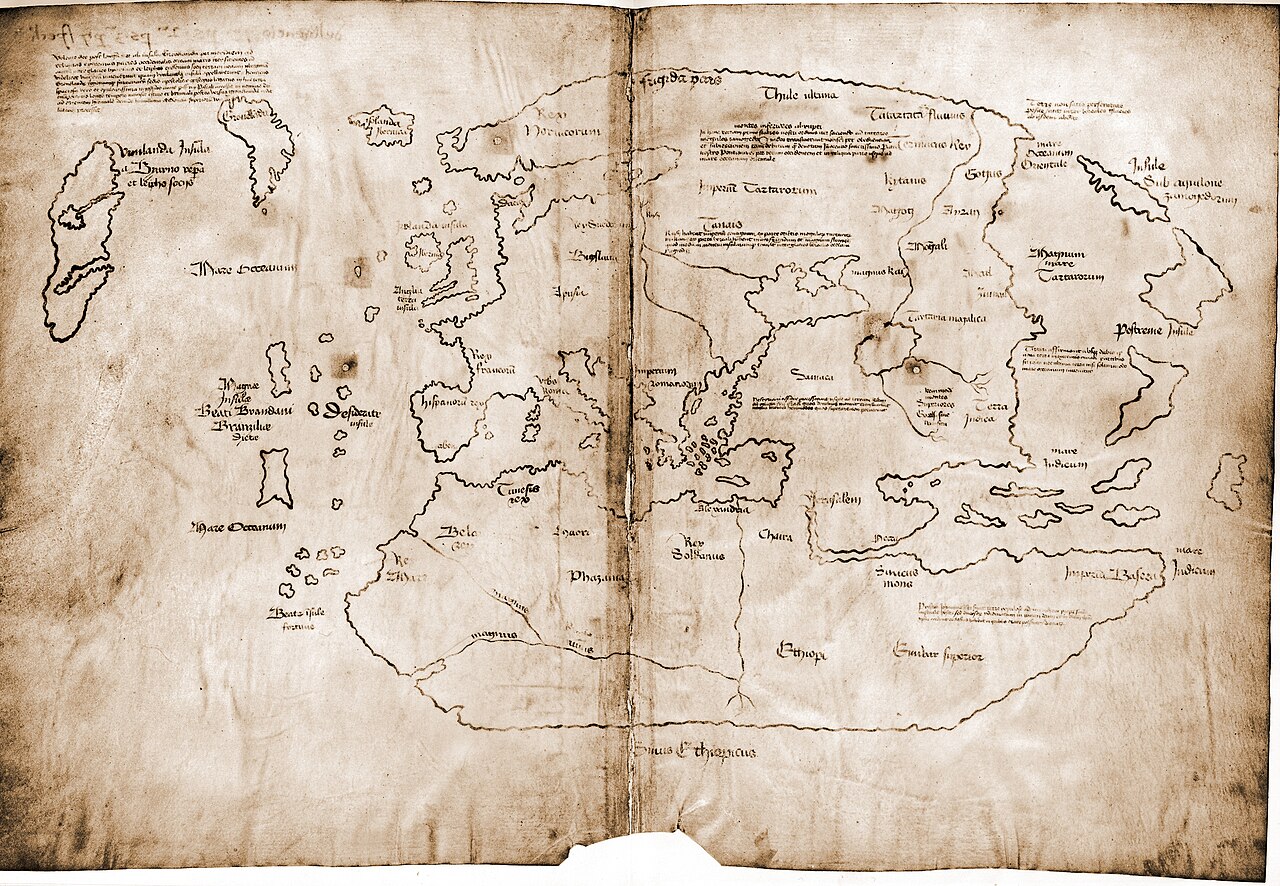

The Vinland Map is modest in size—about 11 by 16 inches—drawn on a single sheet of parchment. Its lines are delicate, its script Gothic. At first glance, it resembles other medieval world maps, with Europe, Africa, and Asia represented in recognizable but distorted form. Greenland, however, is clearly delineated as an island, and to the west lies another large landmass labeled “Vinland.”

This was the feature that gave the map its name and notoriety. For centuries, Norse sagas told of voyages westward to a rich land with grapes and fertile soil, but until the 1960s, no medieval map had depicted it. Here, in faint but confident ink strokes, was apparent proof that Europeans knew of North America centuries before Columbus.

The map was bound together with a manuscript of Vincent of Beauvais’s Speculum Historiale, a popular medieval encyclopedia, and a brief Latin text known as the Tartar Relation. This pairing seemed to suggest that the Vinland Map was part of a scholarly compilation prepared around 1440, possibly for presentation at the Council of Basel, a major church meeting of the time.

If genuine, the map would radically shift the story of exploration, suggesting that knowledge of the Norse discovery of America was not lost in obscurity but quietly preserved in intellectual circles.

The First Wave of Enthusiasm

The team that announced the map in 1965—Raleigh Skelton, Thomas Marston, and George Painter—presented it as authentic. Yale’s publication emphasized its potential significance: it was “the earliest known cartographic representation of the New World.” For a moment, it seemed as though the academic establishment was prepared to rewrite history.

The map coincided with growing archaeological evidence of Norse presence in North America. In 1960, Helge Ingstad and Anne Stine Ingstad had uncovered Norse ruins at L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland. Suddenly, the sagas were no longer mere folklore—they were corroborated by material remains. The Vinland Map appeared to offer the missing visual confirmation: not only had Vikings reached America, but medieval Europeans had recorded it.

The timing of its appearance amplified its impact. The 1960s were an era of upheaval, when traditional narratives were being questioned. The idea of dethroning Columbus as the “discoverer” of America resonated. The Vinland Map promised to change textbooks, national myths, and global history.

The Seeds of Doubt

Even in the midst of celebration, skeptics raised their eyebrows. Some scholars noted inconsistencies in the Latin inscriptions. The phrasing and spelling did not always match 15th-century conventions. Others pointed out that the geographical outlines seemed oddly modern, especially the depiction of Greenland as an island, something not conclusively proven until the 20th century.

Questions also arose about the map’s provenance. It had surfaced on the antiquarian market in the 1950s, offered to Yale by a Swiss dealer, Enzo Ferrajoli de Ry, who in turn had obtained it from an Italian collector. The chain of custody was murky, with no solid documentation before the mid-20th century. Such gaps always raise suspicion in the world of manuscripts, where forgers often exploit desire for spectacular finds.

Perhaps most worrying was the ink. By the 1970s, chemists examining the map noticed that the ink contained an unusual form of anatase, a crystalline form of titanium dioxide. This raised alarms, as such anatase particles were not known in medieval inks but were common in modern pigments. The specter of forgery loomed larger.

The Chemical Controversy

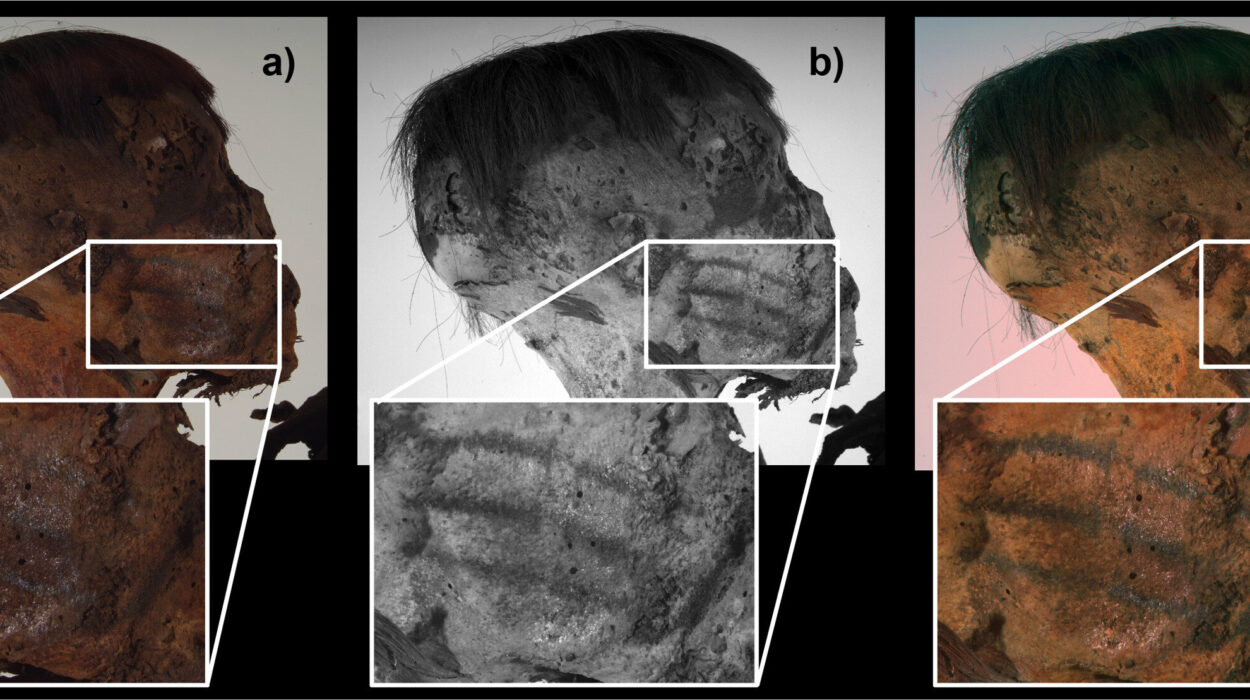

The heart of the debate for decades revolved around the ink. In 1974, Walter McCrone, a microscopist, published results showing that the map’s ink contained anatase particles of a kind produced artificially in the 20th century. McCrone, who had also exposed the Shroud of Turin as a medieval creation, argued bluntly: the Vinland Map was a modern fake.

His findings were fiercely contested. Supporters of the map suggested that anatase could have formed naturally over centuries as the ink degraded. Others accused McCrone of bias or methodological overreach. The controversy intensified, with laboratories across Europe and the United States running tests and publishing conflicting results.

For some, the ink debate symbolized deeper tensions in scholarship: the clash between hard science and traditional humanities, between laboratory data and philological interpretation.

Medievalists and Cartographers Weigh In

While chemists wrangled over anatase, historians and cartographers scrutinized the map’s content. Linguists pointed out that the Latin contained oddities inconsistent with a 15th-century scribe. The form of certain letters, the choice of vocabulary, and even the orthography raised red flags.

Cartographic historians noted that the Vinland Map borrowed heavily from known sources, especially the 15th-century maps of Andrea Bianco. The outlines of Europe and Africa seemed suspiciously similar, as though someone had copied and slightly altered existing maps. More damningly, some features appeared to reflect knowledge not widespread in the 15th century—for example, the accurate depiction of Greenland as an island.

To critics, these details suggested that the map was not a product of medieval scholarship but of a modern hand attempting to mimic it, drawing on accessible sources and retrofitting details to make it appear ancient.

Nationalism, Identity, and Desire

Why did the Vinland Map matter so much? Part of the answer lies in cultural identity. The narrative of Columbus “discovering” America had long been central to European and American self-understanding. A map that placed Norse explorers at the forefront, centuries earlier, disrupted this story. For Scandinavian communities, the Vinland Map was a point of pride, validating sagas often dismissed as legends. For others, it symbolized a shift away from Eurocentric triumphalism.

At the same time, the sheer drama of the map—surfacing from obscurity, tied to mysterious dealers, challenging orthodox history—made it irresistible. Scholars and the public alike wanted it to be real. Human longing for lost knowledge, for dramatic revelations, played into the controversy. The debates were not only about ink and parchment but about identity, pride, and the romance of discovery.

Decades of Debate

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the Vinland Map remained in limbo. Conferences, books, and journal articles proliferated. Some declared it a fake, others defended its authenticity, and many sat uneasily in between.

Yale itself maintained a cautious position, displaying the map but acknowledging doubts. The university had invested prestige and resources in its unveiling, and abandoning it as a forgery risked embarrassment. Thus, the map remained in a kind of scholarly purgatory—famous but contested, iconic yet uncertain.

21st-Century Reappraisals

The turn of the century brought new technologies to bear. Advanced spectroscopic analysis allowed for more precise chemical characterization. A 2002 study again found modern anatase in the ink, concluding strongly in favor of forgery. Yet defenders still argued for natural explanations.

In 2018, Yale University Library launched a comprehensive new investigation, bringing together chemists, conservators, and historians. The results, published in 2021, were decisive. The ink contained synthetic anatase, characteristic of modern pigments manufactured only since the 1920s. Furthermore, radiocarbon dating of the parchment showed it was genuine medieval material, but this was consistent with forgery—authentic old parchment could be acquired and reused by a modern forger.

The conclusion was inescapable: the Vinland Map was not a 15th-century artifact but a 20th-century creation, most likely fabricated in the 1950s.

The Forger’s Hand

Who forged the map, and why? The mystery remains. Some suspect it was the work of a skilled dealer seeking profit by creating a sensational object for the antiquarian market. Others speculate about ideological motives, perhaps tied to nationalism or the desire to elevate Norse contributions to American history.

The precision of the forgery suggests someone with both historical knowledge and access to medieval parchment. But no single culprit has been definitively identified. The map’s shadowy journey through European collectors in the mid-20th century obscures its true origins.

Lessons from the Debate

The Vinland Map saga offers lessons far beyond cartography. It reveals the power of artifacts to capture the imagination and shape national myths. It underscores the importance of scientific analysis in evaluating authenticity, but also the need for interdisciplinary dialogue between scientists and humanists.

It also illustrates the vulnerability of institutions. Yale, eager for prestige, announced the map’s discovery with fanfare, perhaps before thorough vetting. Once invested, it was difficult to retreat. The map became a cautionary tale of how desire and ambition can cloud judgment.

Above all, the debate highlights the human hunger for stories that connect us to the past. The possibility that medieval Europeans knew of America long before Columbus appealed to a sense of wonder, disruption, and justice for marginalized narratives. Even after its exposure as a forgery, the map retains symbolic power because it speaks to our longing for history to surprise us.

The Shadow of Authentic Vinland

Ironically, the Vinland Map’s debunking does not diminish the reality of Norse exploration. Archaeological evidence at L’Anse aux Meadows proves beyond doubt that Vikings reached North America around the year 1000. The sagas, once doubted, now stand as valuable historical sources. The Vinland Map, though false, helped draw attention to this genuine history.

In some ways, the forgery distorted the narrative by making Norse exploration dependent on a contested artifact. But in another sense, it amplified interest, spurring debates that brought Norse history into the spotlight.

Conclusion: A Fraud with Meaning

The Vinland Map is almost certainly a forgery, yet it remains one of the most studied and discussed maps in the world. Its story is not about medieval discovery but about modern hopes, deceptions, and the complicated relationship between evidence and belief.

Authenticity debates around the Vinland Map reveal as much about the 20th century as they do about the 15th. They show how the past is not merely discovered but constructed—shaped by the artifacts we find, the meanings we attach, and the desires we project.

Today, the Vinland Map is displayed at Yale with clear acknowledgment of its inauthenticity. It no longer stands as proof of medieval transatlantic knowledge. Instead, it endures as a cautionary tale, a symbol of scholarly controversy, and a reminder that history is always vulnerable to the seductive power of myth.

And perhaps that is the true lesson of the Vinland Map: that in our quest to uncover the past, we must always balance wonder with skepticism, passion with precision, and imagination with evidence. Only then can we navigate the shifting terrain between history and illusion.