Long before written language, long before kings ruled cities or pyramids pierced the skies, a group of humans—remarkable and yet little understood—left their quiet mark in a cave tucked into the limestone cliffs of what is now northern Israel. They were artists, toolmakers, travelers. They were Aurignacians. And for a fleeting few millennia, they lived and thrived in the Levant, leaving behind a puzzle that modern science is only just beginning to piece together.

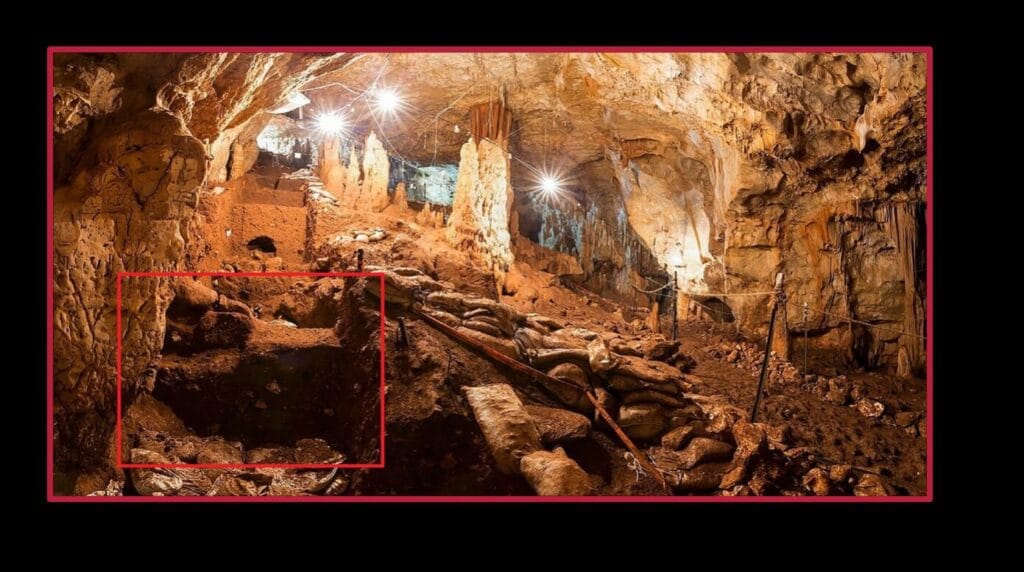

At the center of this mystery lies Manot Cave, a prehistoric shelter in the Western Galilee, whose damp air and secluded darkness preserved secrets that have survived more than 40,000 years. Here, inside this natural vault of time, six human teeth were found. To most, teeth may seem mundane. But to scientists, these teeth were a Rosetta Stone—fragments of the lives and movements of early modern humans and their Neanderthal cousins.

The Aurignacian Enigma: Who Were They?

For decades, the Aurignacians have held a special place in the story of human evolution. Their culture, which first bloomed in Europe around 43,000 years ago, signaled a burst of innovation and symbolism never seen before. They created the first known musical instruments, crafted intricate jewelry, decorated the dark interiors of caves with animals and abstract shapes, and made tools from bone with extraordinary care. Wherever they went, they brought with them a new way of thinking—one that was rich in imagination, artistry, and complexity.

But their origins and their fate have remained steeped in uncertainty. Were the Aurignacians entirely Homo sapiens? Did they outcompete and replace the Neanderthals, or did they merge with them? And why, after such a dazzling cultural surge, did their presence in some regions vanish almost as quickly as it arrived?

The new study by researchers at Tel Aviv University, the Israel Antiquities Authority, and Ben-Gurion University adds a vital piece to this unfolding narrative. It tells us that the Aurignacians who reached the Levant around 40,000 years ago were not just modern humans—they were a blended lineage, a fusion of Homo sapiens and Neanderthals. And that revelation reframes not just the history of one group, but the history of us all.

Teeth That Remember

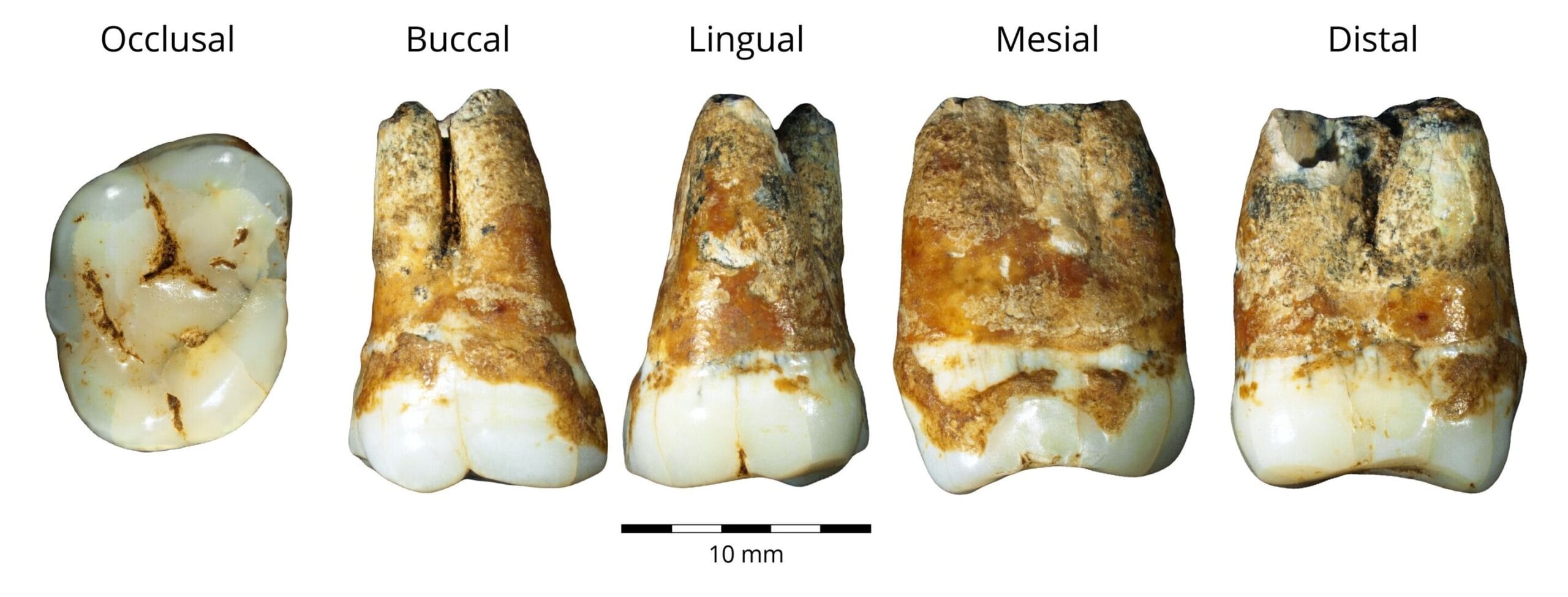

Unlike bone, teeth are resilient. They do not warp as easily with time, and they preserve both physical structure and genetic echoes with stunning clarity. Dr. Rachel Sarig, a dental anthropologist at Tel Aviv University’s School of Dental Medicine and the Dan David Center for Human Evolution, led a team of researchers who used state-of-the-art imaging technologies, including micro-CT scans and 3D analysis, to study the six teeth excavated from Manot Cave.

Their findings were startling. Two of the teeth matched the shape and surface characteristics of Homo sapiens. One was distinctly Neanderthal. And one—a true hybrid—displayed traits of both species, suggesting the individual it belonged to had a mixed ancestry. Until now, this specific combination of traits had only been seen in ancient European populations from the early Upper Paleolithic era.

It was a confirmation of something long suspected but never before observed in this part of the world: The Aurignacians of the Levant were not simply migrants. They were messengers of a deeper story of interbreeding and integration, carrying with them the intertwined legacy of two human lineages.

Europe to the Levant: A Journey in Deep Time

Human migration isn’t just a matter of movement—it’s a reflection of adaptation, resilience, and sometimes, desperation. Around 45,000 years ago, modern humans were pushing across the vast Eurasian landmass. As they entered Europe, they encountered Neanderthals who had lived there for hundreds of thousands of years. For a long time, the dominant narrative was one of conflict—Homo sapiens driving Neanderthals to extinction.

But genetic evidence has told a more nuanced story. Interbreeding, not extermination, was the dominant theme. Most people alive today still carry traces of Neanderthal DNA—proof of ancient unions that took place across Europe and Asia.

Now, the new data from Manot Cave shows that this hybrid population didn’t stay confined to Europe. Some migrated back toward the Near East. They came down from the cold steppes and mountains, following rivers and game trails, perhaps searching for warmer climates or richer hunting grounds. And they brought with them their culture, their tools, their ideas—and their mixed genes.

Dr. Omry Barzilai of the Israel Antiquities Authority, a co-author of the study, emphasizes the significance of this back-migration: “It changes our understanding of population dynamics in the Paleolithic. It’s not just a one-way street from Africa outward. There were waves, returns, integrations. The Levant wasn’t just a crossroads—it was a melting pot of human history.”

A Culture That Shone and Vanished

Armed with tools, creativity, and the kind of brain that could imagine abstract forms and carve flutes from bird bones, the Aurignacians in the Levant thrived—for a time. The researchers estimate that this culture, so rich and expressive, lasted for only 2,000 to 3,000 years in the region.

And then, like a candle extinguished in a gust of wind, they disappeared.

Why? There is no clear answer. Climate fluctuations, dwindling resources, disease, or assimilation into other populations are all possibilities. No evidence of violence or sudden catastrophe has been found. It’s as if they were absorbed into the fabric of other cultures, leaving behind their art, their tools, and their teeth.

This ephemerality makes their legacy even more poignant. For a brief window in deep prehistory, they existed—a fusion of two worlds, two species, expressing their humanity in ways that still touch us tens of thousands of years later.

What the Teeth Tell Us About Ourselves

The hybrid tooth—the one that showed both Neanderthal and Homo sapiens features—is perhaps the most symbolic artifact of all. It represents not just the migration of people, but the mingling of identities, of worldviews, of ways of living. These ancient people were not bound by the divisions we often draw so sharply today. They adapted, interbred, and collaborated across genetic and cultural boundaries.

Their art and tools suggest a species beginning to understand its capacity for symbolism, for aesthetic beauty, and for shared memory. The Aurignacians were not “half-Neanderthal” or “fully modern.” They were human—part of the long, branching story of how we became who we are.

Professor Israel Hershkovitz, another key figure in the study, noted how rare it is to find human remains from this specific window in time in the Levant. “Until now, we hadn’t found any human remains with valid dating from this period in Israel,” he explained. “This groundbreaking study finally gives us a glimpse into the population responsible for some of the world’s earliest and most important cultural innovations.”

Rewriting the Map of Human Evolution

The Manot Cave discovery is more than just a regional curiosity. It helps reshape the broader map of human evolution and dispersal. It challenges the linear, Africa-to-Europe migration model and illustrates a web of movement, connection, and reintegration.

We now know that early modern humans weren’t just replacing Neanderthals—they were merging with them, learning from them, and together creating something new. The Aurignacians in the Levant are living proof of that synthesis, preserved not in myths or monuments, but in the humble enamel of a tooth.

Their time here was brief. Their culture, magnificent. Their legacy, still pulsing in our DNA.

The Cave Still Speaks

Today, the limestone walls of Manot Cave are quiet, broken only by the occasional drip of water echoing into its depths. But within those walls, a voice from 40,000 years ago has spoken—and modern science has finally learned how to listen.

As we uncover more from the Paleolithic record, one thing becomes clear: human history is not a straight path. It is a tapestry of migrations and meetings, of moments of brilliance and stretches of silence. The Aurignacians are one bright thread in that story—one that reminds us how much we owe to those whose names we will never know, but whose lives shaped the world we now call home.

Reference: Rachel Sarig et al, The dental remains from the Early Upper Paleolithic of Manot Cave, Israel, Journal of Human Evolution (2019). DOI: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2019.102648 , dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2019.102648