Deep within the heart of the Atapuerca Mountains in northern Spain, there lies a cave that time forgot. Known as Sima de los Huesos, or “The Pit of Bones,” it holds within its limestone chamber the fossilized remains of nearly 30 ancient hominins. These individuals lived and died over 430,000 years ago, their bones washed into the cave by nature’s whim and sealed away like ancient secrets.

To gaze upon their remains today is to witness a critical chapter in human evolution. Their bones are not quite like ours, yet not wholly alien either. They wear the anatomical signature of Neanderthals, our long-lost cousins—species who once roamed Ice Age Europe, built tools, buried their dead, and vanished tens of thousands of years ago. But these particular fossils, from Sima de los Huesos, carry even deeper mysteries than previously known.

In new research published in Science Advances, Dr. Aida Gomez-Robles, a paleoanthropologist at University College London, has unlocked a profound revelation: the divergence between Neanderthals and modern humans may have occurred at least 800,000 years ago—hundreds of thousands of years earlier than most DNA studies have suggested. And she reached this conclusion not through genomes or skulls—but through teeth.

Tiny Teeth, Titanic Implications

Our molars and premolars are more than just tools for chewing. They are time capsules. Their shapes, sizes, and enamel patterns evolve slowly over tens or hundreds of millennia, leaving behind a record of who we are—and where we came from.

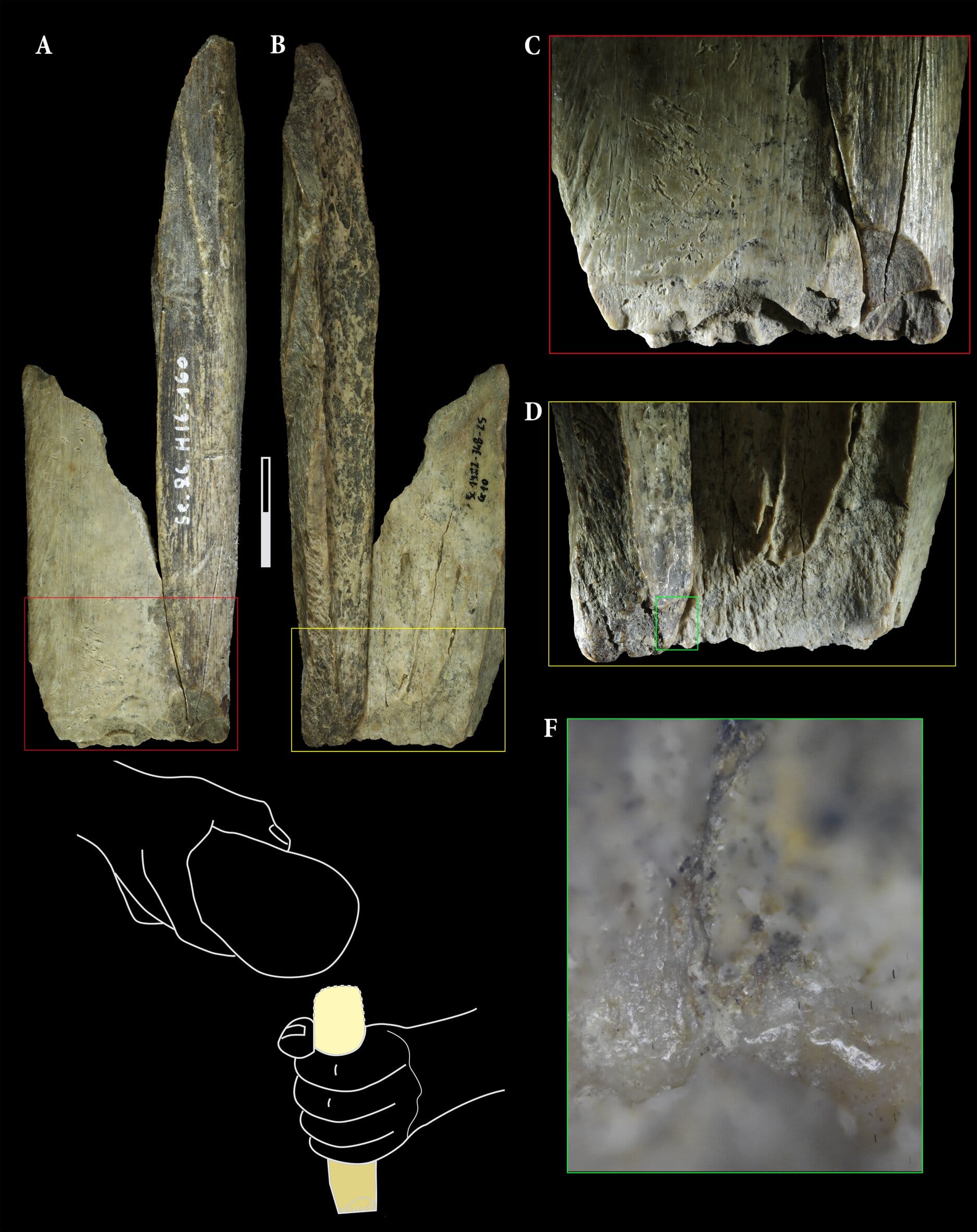

Gomez-Robles and her team conducted a detailed analysis of dental evolution in early hominins, focusing on the Sima de los Huesos fossils. What they found shook conventional understanding: the dental features of these hominins were already distinctly Neanderthal-like, far more advanced along the evolutionary path than one would expect if their divergence from modern humans had occurred only 400,000 or 500,000 years ago, as DNA data often implies.

For these Sima individuals to display such specialized Neanderthal traits, their lineage must have split from ours far earlier. If the split had occurred more recently, the evolutionary changes needed to produce those teeth would have had to happen at an implausibly rapid rate—something almost never observed in hominin evolution.

As Gomez-Robles puts it: “Any divergence time between Neanderthals and modern humans younger than 800,000 years ago would have entailed an unexpectedly fast dental evolution in the early Neanderthals from Sima de los Huesos.”

Rather than defy the established pace of evolution, the simpler and more plausible explanation is this: the evolutionary fork that led to Neanderthals and modern humans occurred earlier than we thought—at least 800,000 years ago.

When Genetics and Anatomy Disagree

For years, our estimates of when modern humans and Neanderthals went their separate evolutionary ways have largely come from genetic studies. Ancient DNA, carefully extracted from bones and teeth, has suggested a split between 300,000 and 500,000 years ago. These estimates have shaped theories about who our last common ancestor was and how long our paths have been diverging.

But fossils don’t always follow the script of genetics. In the case of Sima de los Huesos, the DNA and anatomy seem to be telling different stories. While genetic analyses place the divergence relatively recently, the physical structure—particularly the teeth—suggests a much older split.

This isn’t just a puzzle of timelines. It forces scientists to ask: which source do we trust more when the evidence conflicts? DNA can degrade, especially over hundreds of thousands of years, and its preservation in fossils is rare and partial. Anatomy, on the other hand, leaves behind more complete records—but interpreting it can be subjective.

By focusing on dental evolutionary rates, Gomez-Robles’s study creates a quantitative model—a way to measure how fast traits should change over time under realistic scenarios. And in that model, the only timeline that fits the observed dental changes in early Neanderthals is one that pushes the divergence date back beyond 800,000 years.

What the Teeth Tell Us About Our Ancestors

The teeth of the Sima hominins are remarkably Neanderthal in nature. Their molars and premolars are small, compact, and uniquely shaped—traits not seen in earlier hominins or in modern humans. This suggests that by 430,000 years ago, these individuals were already well along the Neanderthal evolutionary track, having inherited those features from ancestors that had diverged from our own lineage long before.

Gomez-Robles argues that for such changes to appear so early, the last common ancestor of Neanderthals and Homo sapiens must have lived before 800,000 years ago. This pushes us into a different time and landscape—one where Homo heidelbergensis, Homo antecessor, and other enigmatic early humans roamed Europe and Africa, their fossils scattered and stories incomplete.

By eliminating all hominin species postdating 800,000 years ago from the candidate pool of our shared ancestor with Neanderthals, the study rewrites the shortlist. It forces anthropologists to reconsider earlier, more archaic populations as the source of both lineages—and to think more carefully about what traits truly define “modern” and “archaic.”

Rewriting the Story of Us

This finding doesn’t just shift a date on the evolutionary calendar—it reshapes the entire narrative of human evolution.

If our split from Neanderthals occurred 800,000 years ago or earlier, that means both lineages had longer to evolve separately than previously thought. It would also explain why Neanderthals developed such distinct anatomical and cultural traits—like large brow ridges, stocky builds, and complex hunting tools. It wasn’t that they changed rapidly in a short span of time; rather, they had ample evolutionary time to become who they were.

It also means our own lineage—Homo sapiens—has been evolving on a separate track for longer than we assumed. It challenges assumptions about our intellectual and anatomical “modernity,” and suggests that the journey to becoming human began farther back in time, in a much more complex ancestral landscape.

A Long Shadow of Separation

The implications ripple outward. If the Neanderthal-human split happened over 800,000 years ago, we have to reconsider how often—and how deeply—the two lineages may have interacted later. We know that Neanderthals and modern humans interbred when they encountered each other again tens of thousands of years ago in Ice Age Europe. Today, most people outside of Africa carry traces of Neanderthal DNA in their genomes.

But if we’d been evolving apart for twice as long as previously thought, how similar were we when we met again? Did we still understand one another—not just physically, but socially, emotionally, cognitively?

What did it mean to see another human, shaped by 800,000 years of parallel evolution, standing before you in the cold, echoing light of a Pleistocene morning?

Teeth as Time Machines

Science often begins with a question so small it could be overlooked. In this case, it began with teeth—humble, fossilized, yellowed by age. Yet those teeth have become time machines, helping us travel back through hundreds of millennia to glimpse the moment when “us” and “them” began to take shape.

Gomez-Robles’s research doesn’t claim to have the final answer. But it adds clarity to the murky timelines of human evolution and opens new paths for inquiry. It reminds us that the human story is not a single path, but a braided river of branches, tributaries, and divergences.

And sometimes, the most enduring clues are hidden in the smallest bones.

Reference: A. Gómez-Robles at University College London in London, UK el al., “Dental evolutionary rates and its implications for the Neanderthal–modern human divergence,” Science Advances (2019). advances.sciencemag.org/content/5/5/eaaw1268