In November 1922, the world’s imagination was set ablaze when British archaeologist Howard Carter stumbled upon the most famous archaeological discovery of all time: the nearly intact tomb of Pharaoh Tutankhamun in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings. The tomb of the “boy king,” sealed for more than 3,000 years, contained dazzling treasures of gold, statues, chariots, and the iconic golden funerary mask that has since become a symbol of ancient Egypt itself.

But beyond its glittering wealth, the tomb carried something far greater: questions. Even after a century of study, the resting place of Tutankhamun continues to puzzle scientists, historians, and adventurers alike. Why was the tomb so small for a king? Why were the walls hurriedly painted? How did Tutankhamun really die? And is it possible that hidden chambers still lie sealed behind its walls, guarding secrets yet to be revealed?

The story of King Tut’s tomb is not simply one of ancient splendor—it is a tale of mystery, controversy, and the enduring human fascination with death and immortality.

The Boy Behind the Mask

Before delving into the mysteries of the tomb itself, one must first understand the figure at its center. Tutankhamun, born around 1341 BCE, came to the throne as a child of nine and reigned for less than a decade before dying unexpectedly at about eighteen or nineteen years of age. He was a relatively minor pharaoh in Egypt’s long history, overshadowed by rulers like Ramses II or Hatshepsut.

And yet, his tomb’s discovery ensured his immortality. Ironically, Tutankhamun’s obscurity during life may have been the very reason his tomb remained hidden and intact. More prominent rulers’ graves had been looted centuries earlier, stripped of treasures and robbed of their sanctity. Tutankhamun, buried in a modest, hastily prepared tomb, was overlooked until Carter’s discovery.

But the boy king’s death has fueled endless speculation. Was he murdered, as early X-rays suggested? Did he suffer from genetic disorders due to inbreeding within the royal family? Or was it an accident—a broken leg complicated by malaria—that sealed his fate? These questions remain unresolved, and they feed directly into the mysteries surrounding his burial.

A Tomb Too Small for a Pharaoh

One of the first puzzles archaeologists noticed about Tutankhamun’s resting place was its size. Compared to the sprawling tombs of other pharaohs in the Valley of the Kings, KV62—the designation for Tutankhamun’s tomb—is strikingly small. It consists of only four main chambers, far less elaborate than those of other New Kingdom rulers.

Why would a king, even a relatively minor one, be buried in such a cramped space? Scholars suggest several possibilities. Perhaps Tutankhamun’s death was sudden and unexpected, leaving little time to construct a proper royal tomb. In that case, an unfinished tomb meant for a lesser noble may have been repurposed for the king.

Another theory ties into ancient Egyptian politics. Tutankhamun came to power during a turbulent time, following the controversial reign of Akhenaten, who had attempted to overthrow traditional Egyptian religion in favor of worshiping a single deity, the Aten. In restoring the old gods, Tutankhamun may have angered powerful factions. Was his burial deliberately rushed and diminished by rivals, ensuring his memory would fade quickly?

The small tomb, crammed with treasures almost too large for its chambers, suggests haste. But it also whispers of something deeper—perhaps an unfinished story still hidden within its walls.

The Hastily Painted Walls

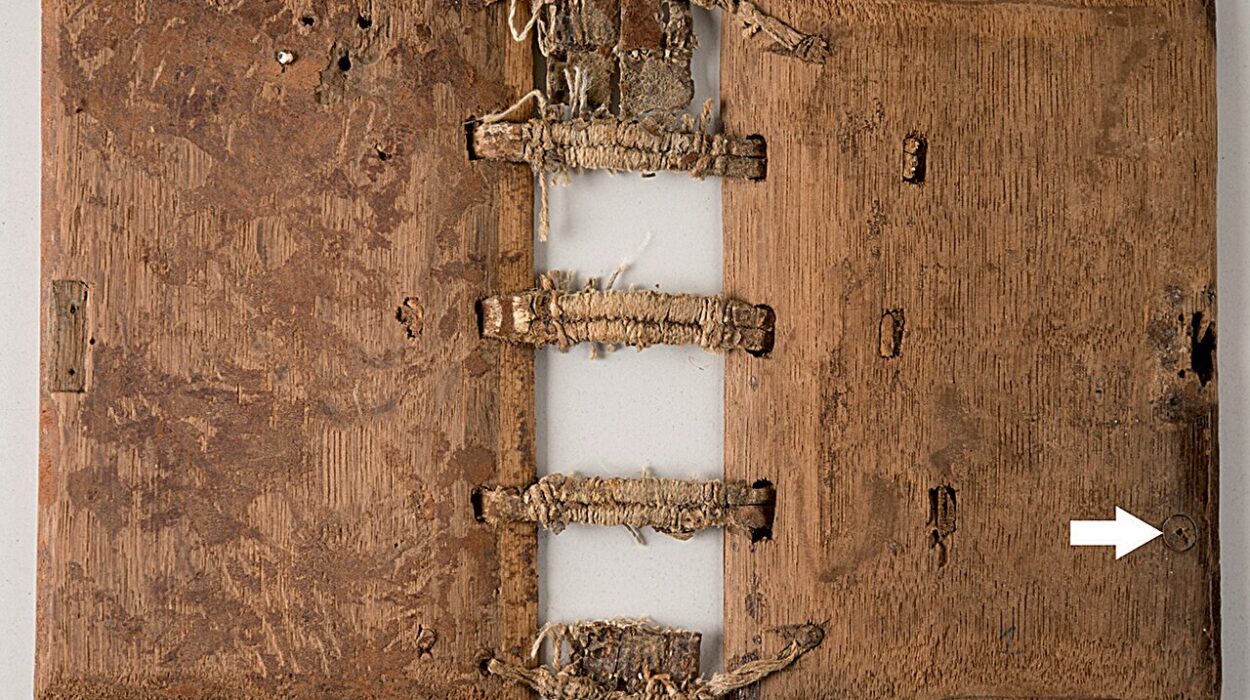

Another enduring mystery lies in the decoration of the burial chamber. Unlike the detailed and carefully executed art that adorns other royal tombs, the paintings on Tutankhamun’s walls appear crude and rushed. Brushstrokes are uneven, figures lack detail, and parts of the artwork seem almost incomplete.

Scientific analysis has even revealed strange blotches on the walls—dark brown spots caused by microbial growth. These spots suggest the paint may not have fully dried before the tomb was sealed, indicating a burial conducted in extraordinary haste.

Why the rush? Was Tutankhamun’s death unexpected, leaving priests scrambling to perform funerary rites before the body decomposed in the harsh Egyptian heat? Or was the haste politically motivated, with the young king’s death ushering in a power struggle that demanded immediate resolution?

The imperfect artwork stands as silent testimony to a burial unlike any other. It feels less like a royal celebration of eternal life and more like an emergency, a hurried attempt to honor a pharaoh before time ran out.

How Did Tutankhamun Die?

No question about Tutankhamun has inspired more speculation than the cause of his death. When his mummy was first examined in the 1920s, early X-rays suggested a fatal blow to the head, fueling theories of assassination. Was Tutankhamun murdered in a palace coup, his reign cut short by ambitious advisers?

Later CT scans complicated the story. Evidence emerged of a broken leg, perhaps sustained in a chariot accident, which may have become fatally infected. DNA analysis revealed traces of malaria in his remains, suggesting the young king battled disease as well.

But even today, scholars remain divided. Some argue that Tutankhamun suffered from congenital disorders caused by the inbreeding common in royal families. His clubfoot, cleft palate, and weakened immune system may have left him vulnerable. Others insist that foul play cannot be ruled out, pointing to political rivals such as Ay, the vizier who succeeded him, or Horemheb, a general who later seized the throne.

The truth may never be known. Tutankhamun’s body was badly damaged, possibly during Carter’s excavation, making forensic evidence unreliable. Still, the mystery of his death lingers, shaping every interpretation of his tomb.

The Treasures That Defy Explanation

The treasures found within the tomb are dazzling, but they too raise questions. Among them were chariots, furniture, jewelry, statues, and the famous golden mask that covered Tutankhamun’s mummified face. But not all these items seem to belong to him.

Some objects bear the names of other pharaohs, suggesting they were repurposed for Tutankhamun’s burial. His golden mask, upon close inspection, appears to have originally been made for a woman—perhaps Nefertiti, Akhenaten’s queen. Could Tutankhamun’s tomb contain remnants of another ruler’s burial goods, hurriedly adapted for him in the rush to prepare his grave?

This raises tantalizing possibilities. Was Tutankhamun buried in a tomb not originally meant for him, using treasures intended for someone else? And if so, who was that someone?

Are There Hidden Chambers?

Perhaps the most thrilling mystery of Tutankhamun’s tomb is the possibility that it still holds undiscovered chambers. In 2015, archaeologist Nicholas Reeves proposed that behind the tomb’s north wall might lie sealed doorways leading to additional rooms—possibly even the lost burial chamber of Queen Nefertiti.

Ground-penetrating radar scans revealed anomalies that could suggest hidden voids, though results remain disputed. Some scientists argue that the anomalies are simply natural variations in the rock, while others believe the evidence is strong enough to warrant further exploration.

If hidden chambers do exist, they could revolutionize our understanding of Egypt’s 18th Dynasty. Could Tutankhamun’s tomb be a mere annex to a larger, more important burial—one that still waits, undisturbed, beyond the painted walls?

The Curse of the Pharaohs

No discussion of Tutankhamun’s tomb is complete without the infamous “curse.” Soon after the tomb’s opening, stories spread of those who entered suffering mysterious deaths. Lord Carnarvon, Carter’s patron, died suddenly in Cairo from an infected mosquito bite. Newspapers seized on the story, fueling legends that the tomb carried a curse upon any who disturbed it.

Modern science dismisses the curse as superstition. The deaths can be explained by coincidence, infection, or even toxic mold spores released from the sealed chambers. Yet the legend endures, adding to the tomb’s aura of mystery. Even skeptics cannot deny the power of the narrative: that ancient kings may still wield influence from beyond the grave.

What the Tomb Tells Us About Ancient Egypt

Beyond its mysteries, Tutankhamun’s tomb offers invaluable insights into the culture, religion, and daily life of ancient Egypt. The treasures within reflect not only wealth but also deep spiritual beliefs. The golden mask, inlaid with lapis lazuli and quartz, was not mere ornament—it was a protective device, meant to guide the king’s soul into eternity.

The walls, though hastily painted, depict rituals designed to secure Tutankhamun’s place among the gods. The presence of everyday objects—beds, sandals, even toys—shows how Egyptians imagined the afterlife as a continuation of earthly existence.

The tomb also reflects political turbulence. The reused treasures, the modest chambers, the hurried burial—all point to a time of upheaval, when Egypt struggled to restore stability after Akhenaten’s radical religious revolution. Tutankhamun’s tomb is as much a record of crisis as it is of glory.

A Century of Study, a Future of Mystery

More than one hundred years have passed since Carter first peered into the tomb by candlelight and declared he saw “wonderful things.” And yet, the wonder endures. Every scientific advance, from CT scans of the mummy to chemical analysis of pigments, raises new questions even as it answers old ones.

The tomb is no longer just a burial chamber—it is a mirror reflecting humanity’s endless curiosity. It reminds us that history is not fixed but alive, shaped by new discoveries and interpretations.

Perhaps hidden chambers will one day be revealed, perhaps not. Perhaps science will finally uncover the truth of Tutankhamun’s death, or perhaps it will remain forever ambiguous. But the mystery itself is part of the magic.

Conclusion: The Eternal Allure of King Tut

Inside King Tut’s tomb lies more than gold and relics. There lies a story of power and fragility, of youth cut short, of mysteries unresolved. There lies the enduring human quest to understand life, death, and what may come after.

The boy king, forgotten by history, has become immortal not through conquest or achievement but through mystery. His tomb, modest yet magnificent, reminds us that even the smallest of discoveries can shake the world.

And so, the tomb of Tutankhamun remains not just a burial site but a riddle. Each object, each wall, each unanswered question whispers to us across millennia, calling us to look deeper, to wonder, to never stop searching. In the silence of that ancient chamber, the mysteries of life and death still echo—waiting for us to listen.