On a wind-polished stretch of the Ligurian coast in northwestern Italy, the Arene Candide Cave has long guarded the secrets of its prehistoric inhabitants. But now, a team led by the University of Florence has uncovered a discovery that reshapes not just a skull, but our understanding of cultural identity deep in human history.

In a study published in Scientific Reports, researchers reveal the earliest known Eurasian case of artificial cranial modification (ACM), a deliberate reshaping of the skull performed in infancy. The specimen, known as AC12, lived between 12,620 and 12,190 years ago, making this the oldest documented example of the practice on the continent.

“This isn’t just anatomy,” the authors note. “It’s biography — a personal story etched into bone by the hands of a community.”

The Ancient Art of Shaping Identity

Artificial cranial modification, sometimes called intentional cranial deformation, has been documented across the globe — from the high Andes to the steppes of Central Asia — and across thousands of years. The method is deceptively simple: apply pressure to an infant’s soft skull before the cranial bones fuse, using boards, bindings, or padding to guide the head into a specific shape.

Two main styles dominate the archaeological record. Tabular modification uses rigid boards to flatten the back and sometimes the front of the skull, creating a broad, wide-headed look. Annular modification uses bands of cloth to gently but persistently squeeze the head, producing a long, tapering profile. AC12 falls into the second category — the annular type — with a cranium elongated like a tapering vase.

Such shaping was never merely cosmetic. In many societies, head form signaled belonging, status, or heritage. It was a visible, permanent marker of who you were and where you came from — a living artifact of cultural identity that could be passed from generation to generation.

A Burial with a Story

The burial of AC12 was as deliberate as the shaping of the skull. The individual’s cranium was placed carefully atop another burial, AC15, inside a stone niche. The jaw and other bones lay in a nearby secondary cluster, suggesting a multi-stage funerary process. This wasn’t a haphazard deposition; it was part of a complex ritual program within the Epigravettian necropolis that occupied the cave between 12,900 and 11,600 years ago.

Among at least 22 individuals buried here, AC12 is one of only five with an intact skull — and the only one to bear clear signs of modification. That rarity hints at a selective practice, perhaps reserved for a particular subgroup or family line, rather than a community-wide tradition.

Science in the Digital Age Meets the Stone Age

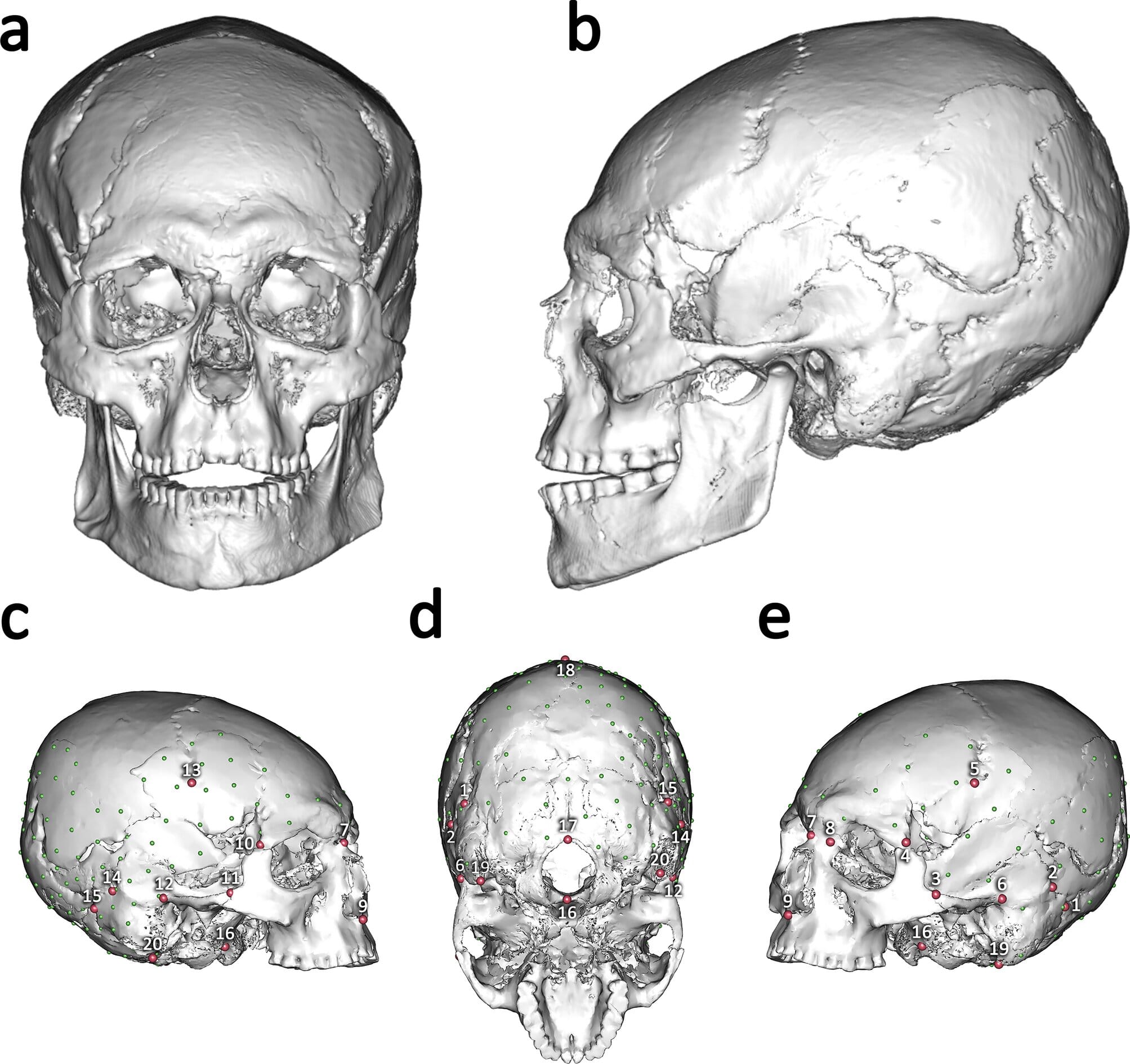

Although AC12’s skull is thousands of years old, the investigation combined cutting-edge tools with old-fashioned archaeological precision. The team used virtual anthropology and geometric morphometrics to digitally reconstruct the cranium from CT scans. They mirrored fragments, aligned them using 3D software, and mapped anatomical landmarks before comparing the skull’s proportions to hundreds of others — including Late Upper Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic, pathological, and known ACM cases worldwide.

The results were decisive. In every statistical test, AC12 clustered with annular-type ACM individuals and fell outside the range of naturally occurring shapes or pathological conditions like craniosynostosis. Logistic regression models classified AC12 as ACM with 93% to 100% accuracy, depending on the dataset.

The conclusion: this skull wasn’t shaped by accident or disease. It was crafted by human intent.

A Tradition Older Than We Thought

Until now, Europe’s earliest evidence of cranial modification came from much later periods. AC12 pushes the practice back into the Late Upper Paleolithic, showing that even Ice Age hunter-gatherers used body modification to express and transmit cultural identity.

Why would such a small, mobile community invest in reshaping their children’s skulls? The authors suggest it was a marker of ascribed identity — a way to bind infants to a group’s traditions from the moment of birth, signaling belonging in a landscape where alliances and recognition could mean survival.

The fact that only one skull in the assemblage bears this feature suggests the practice wasn’t universal, but rather a signal of subgroup distinction, perhaps denoting a family lineage, elite status, or a role within the community.

A Message from the Past

The discovery of AC12 is more than a scientific milestone. It’s a rare chance to glimpse the intimate human choices behind an archaeological artifact. It tells us that, 12,000 years ago, people on the Ligurian coast were already thinking in terms of identity, heritage, and symbolism — concepts as human as language or art.

As lead researchers point out, the practice shows that “even in the deep past, the human body was a cultural canvas.” And while we may never know AC12’s personal story, their skull carries a message across millennia: the need to shape not only our tools and shelters, but ourselves, is as old as humanity.

More information: Tommaso Mori et al, Early European evidence of artificial cranial modification from the Italian Late Upper Palaeolithic Arene Candide Cave, Scientific Reports (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-025-13561-8