Along a coast shaped by water and time, at a place known today as Terra Amata in Niza, Francia, the ground once carried the footsteps of humans who lived 400,000 years ago. This was not a fleeting visit. Again and again, season after season, human groups returned to this marshy landscape beside a delta, leaving behind quiet but powerful traces of their lives. Now, those traces are speaking more clearly than ever.

A new study published in the Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology by archaeologist Paula García Medrano, a researcher at the Centro Nacional de Investigación sobre la Evolución Humana, brings fresh attention to this remarkable site. By closely examining its stone tools, the research opens a vivid window into how some of the earliest humans in western Europe organized their lives, shaped their technologies, and moved through their territory.

Terra Amata has long been known as a key location for understanding the evolution of human behavior. What this study does is deepen that story, revealing how innovation can hide within simplicity and how even modest tools can carry the fingerprints of changing minds.

A Place Humans Chose Again and Again

Terra Amata was not an accident of survival. The site sits next to a delta, in an environment that was once marshy and rich, offering opportunities that made it worth returning to. Human groups occupied the area seasonally and repeatedly, suggesting planning rather than chance.

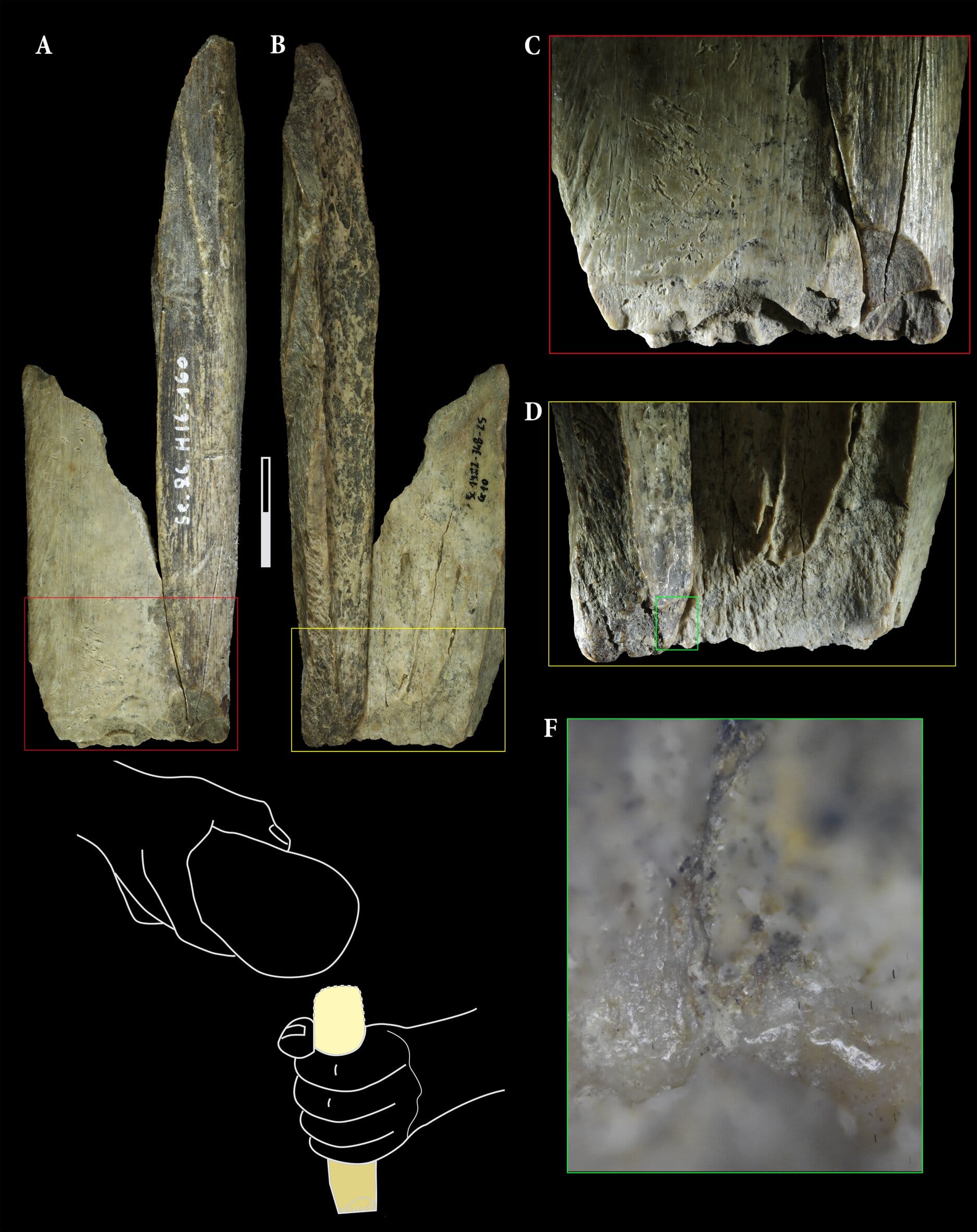

What makes this especially striking is what the site already tells us. There is evidence of fire use. There are signs of hut construction. There is proof that people transported raw materials from locations about 40 kilometers away, even though suitable stone was available right where they lived.

“These indications reveal a notable degree of organization and territorial mobility and have made Terra Amata a reference site for understanding human occupation in Europe,” explains García Medrano.

This was not a population simply reacting to its environment. It was one that understood space, resources, and timing. Terra Amata was part of a broader territory, connected to distant places and repeated journeys.

Stones That Carry Human Decisions

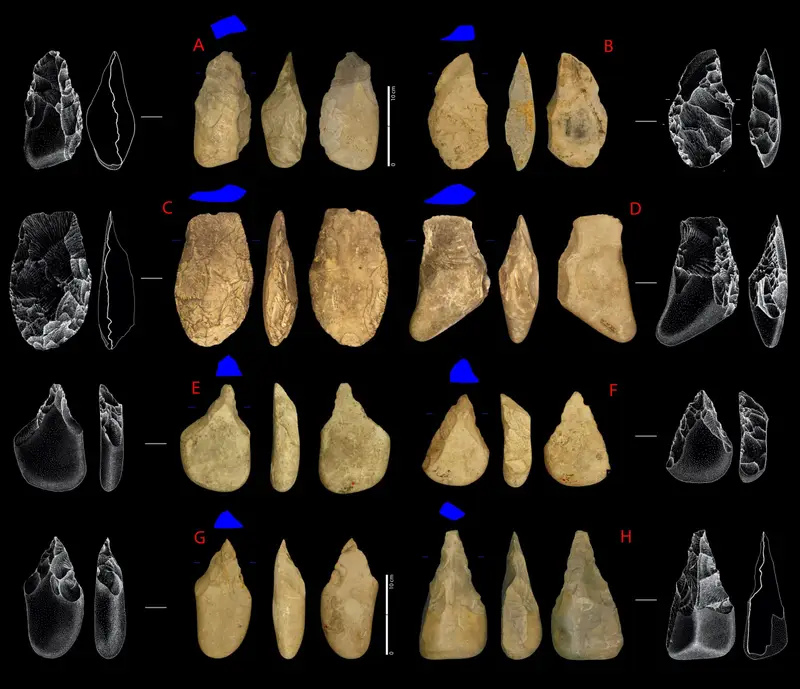

At the heart of the new study lies a detailed technological and morphometric analysis of the stone tools, known as lithic remains, found at the site. These objects may appear humble at first glance. Most of the tools were made from local limestone cobbles, stones that could be picked up nearby and worked without elaborate preparation.

The methods used to shape them were straightforward. The knapping strategies were simple, the reduction sequences short, and the natural shape of each cobble strongly influenced the final tool. Everything about these artifacts suggests practicality and efficiency rather than showmanship.

Yet this apparent simplicity is misleading. When examined closely, these stones reveal choices, planning, and technical understanding. They are not random products. They are the outcome of deliberate actions taken by skilled hands.

Innovation Hidden in Plain Sight

What makes the Terra Amata tools especially important is that, within their simple appearance, they contain subtle but significant innovations. The study identifies structured centripetal flaking, platform preparation, and hierarchical core organization in the production process.

These are not trivial details. They show that toolmakers were beginning to think differently about how stone could be shaped, how force could be controlled, and how a core could be managed over time to produce usable flakes.

“These are incipient features that anticipate the later Levallois tradition,” notes García Medrano.

This observation places Terra Amata at a critical moment. The tools are not yet part of the fully developed Levallois technique, but they hint at the ideas that would later define it. They show experimentation, transition, and the early stages of a technological shift.

A Mosaic of Cultures Taking Shape

Rather than presenting a single, uniform path of progress, the findings from Terra Amata reinforce a more complex picture of human evolution in western Europe during the Middle Pleistocene. The study supports the idea of a cultural mosaic, where different human groups were exploring diverse technical strategies and ways of living.

At Terra Amata, this mosaic takes the form of adaptable toolmaking, flexible subsistence behaviors, and intelligent territorial management. The people who lived here were not simply copying a fixed tradition. They were responding to their surroundings, balancing local resources with distant connections, and refining their tools to meet daily needs.

This diversity suggests that human evolution was not a straight line but a branching process, shaped by environment, opportunity, and creativity.

Daily Life Written in Stone

Stone tools are often treated as abstract data points, but at Terra Amata they feel personal. Each cobble selected, each strike delivered, reflects a moment in someone’s day. A tool might have been made to cut, to scrape, or to process materials needed for shelter or fire.

The presence of fire use and hut construction adds depth to this picture. These were people who shaped their environment, creating spaces to live and gather. The tools they made were part of that broader system, supporting tasks that made repeated occupation possible.

Transporting raw materials from as far as 40 kilometers away, despite local abundance, hints at foresight and perhaps social connections beyond the immediate area. It suggests routes, memory, and planning across landscapes.

Terra Amata Reaffirmed

With this new study, Terra Amata’s importance becomes even clearer. The site does not just preserve tools. It preserves a moment when human technology was beginning to change in subtle but meaningful ways.

“We can state that the Terra Amata site is confirmed as a fundamental location for understanding the evolution of technology and the adaptation to new daily-life needs of the first humans in Europe,” concludes García Medrano.

This confirmation matters because it anchors big questions in real evidence. How did early humans adapt to new environments. How did technology evolve before major breakthroughs became visible. How did behavior, mobility, and innovation intertwine.

Why This Research Matters

This research matters because it shows that human progress does not always announce itself loudly. Sometimes it appears in quiet refinements, in small changes to familiar practices, in stones shaped just a little differently than before.

By focusing on the lithic industry of Terra Amata, the study reveals how early humans balanced simplicity with innovation, using local materials while experimenting with new ideas. It highlights a period when technological traditions were not fixed but flexible, shaped by intelligence and adaptation.

Understanding this moment helps explain how later, more complex technologies emerged. It reminds us that the foundations of human ingenuity were laid not in sudden revolutions, but in patient, thoughtful engagement with the world.

At Terra Amata, 400,000 years ago, humans were already learning how to shape not only stone, but their future.

More information: Paula García-Medrano et al, Technological Strategies and Diversity of Management of Limestone Pebbles at the Site of Terra Amata (southeast, France) in the Context of MIS11 in Western Europe, Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology (2025). DOI: 10.1007/s41982-025-00242-1