More than eight thousand years ago, the climate of the Northern Hemisphere shifted abruptly. Temperatures dropped. Rainfall patterns changed. Landscapes that had once supported human life with relative stability suddenly became uncertain. For many communities across the North China Plain, this moment marked disruption, abandonment, and collapse. Yet one settlement, nestled among rivers and water channels in what is now Henan Province, did something unexpected. Jiahu endured.

A recent study led by Dr. Yuchen Tan and colleagues tells this story not as a simple tale of catastrophe, but as a nuanced human drama of adaptation, reorganization, and resilience. Published in the journal Quaternary Environments and Humans, the research challenges the long-standing idea that the 8.2 ka climate event was uniformly devastating for all populations in the region. Jiahu, the study shows, was not merely a victim of climate change. It was an active participant in shaping its own survival.

A Sudden Shock Written in Ice and Sky

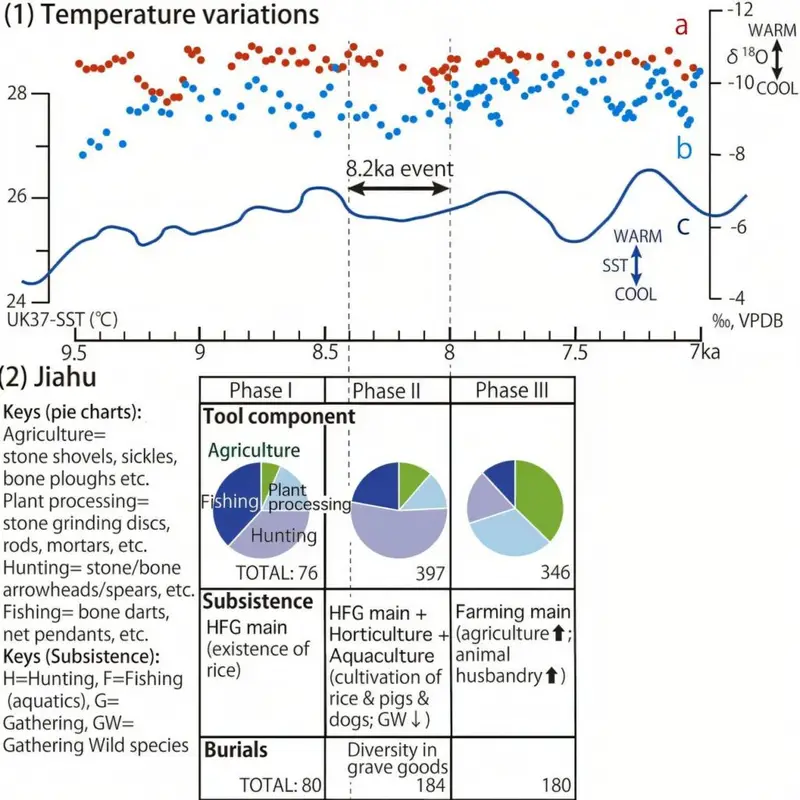

The event at the heart of this story is known as the 8.2 ka event, named for the time it occurred around 8,200 years ago during the Holocene. It was first identified far from China, preserved in the layers of Greenland ice cores. Those frozen records revealed an abrupt and short-lived climatic disruption that sent ripples across the Northern Hemisphere.

The cause lay in a dramatic collapse of the Laurentide ice sheet in North America. As massive amounts of freshwater poured into the North Atlantic, they weakened the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, a crucial component of large-scale climate systems. This weakening did not stay confined to the Atlantic. It forced a southward shift of the Intertropical Convergence Zone, a system deeply tied to the East Asian Summer Monsoon.

For regions dependent on this monsoon, including the North China Plain, the consequences were severe. Cooling temperatures and drought set in. Landscapes that had once provided reliable resources became harder to live in. Archaeological records from many sites in Northern China reflect this stress, showing significant disruption or even complete abandonment during this period.

Against this backdrop, Jiahu’s persistence stands out like a quiet defiance.

Life Along a Web of Water

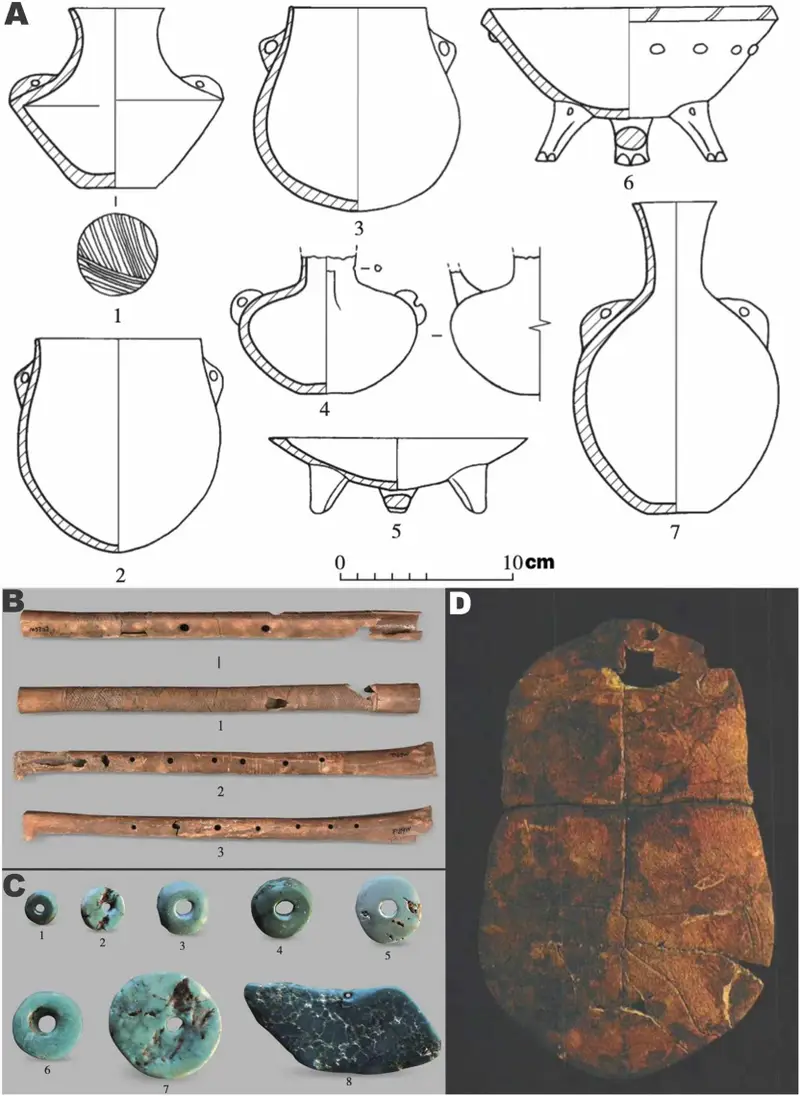

Jiahu was occupied between 9.5 and 7.5 ka BP, long before the climate shock struck. Its location was not accidental. The surrounding landscape was shaped by thousands of rivers and small water channels, creating a resource-rich environment that supported early human settlement. Water, food, and fertile land were woven together in a way that allowed the community to flourish.

When the 8.2 ka event arrived, Jiahu was expected to follow the same path as many of its neighbors. The event has often been described as catastrophic in Northern China, and for good reason. Many contemporary sites experienced dramatic decline. Yet Jiahu did not vanish from the archaeological record. Instead, it changed.

The question Dr. Tan and colleagues set out to answer was not simply whether Jiahu survived, but how it did so.

Rethinking Resilience in the Ancient World

To unravel this mystery, the researchers turned to resilience theory, a framework originally developed in ecology to understand how systems absorb disturbances and reorganize in response. Over time, this theory has been criticized for being vague and for drifting too close to environmental determinism, where human agency fades into the background.

To overcome these limitations, the research team adapted a more structured approach inspired by modern disaster management. They turned to the Baseline Resilience Indicator for Communities, or BRIC, a model typically used to assess how contemporary communities handle natural disasters. The model examines factors such as social organization, economic systems, institutions, infrastructure, and community dynamics.

“…Our aim in adapting BRIC was to provide a transferable framework for examining how human systems reorganize in response to abrupt climatic or environmental change across a wider range of sites,” Dr. Tan explained.

The challenge was translating a modern framework into an archaeological context. Ancient societies did not leave behind policy documents or economic statistics. What they left instead were bones, burials, tools, and settlement patterns.

“Resilience is a universal concept. Even though ancient societies are very different from modern towns, they also needed to reorganize, redistribute labor, strengthen cooperation, and adjust their use of resources when facing sudden change,” Dr. Tan continued.

By grounding the model in archaeological indicators rather than impressions, the team aimed to make resilience measurable rather than speculative.

“By adapting BRIC, we translated its core principles to archaeological indicators. This allowed us to evaluate resilience in a structured and comparable way rather than relying on impressionistic interpretations.”

A Community Under Pressure Begins to Transform

The researchers examined evidence from three phases of Jiahu’s occupation. Phase I, spanning from 9.0 to 8.5 ka BP, reflects life before the climate crisis. Phase II, from 8.5 to 8.0 ka BP, coincides directly with the 8.2 ka event. Phase III, from 8.0 to 7.5 ka BP, represents the period after the event subsided.

It is Phase II that tells the most compelling story.

During this period, the number of burials surged dramatically. From 88 in Phase I, burials increased to 206 in Phase II. This sharp rise likely reflects a combination of increased mortality during a stressful climatic period and an influx of migrants from surrounding regions whose own settlements may have been struggling or collapsing.

As people arrived and pressures mounted, burial practices changed. They became more standardized, and grave goods increased significantly. These shifts suggest emerging wealth disparities and growing social stratification. Jiahu was not simply absorbing people; it was reorganizing itself socially.

Skeletal evidence adds another layer to the story. Analysis revealed a greater division of labor during Phase II. Males showed higher rates of osteoarthritis, hinting at increased involvement in strenuous physical activities. This suggests that labor was being redistributed, perhaps to meet the heightened demands of food production and resource management under harsher climatic conditions.

What might look like social strain at first glance may have been part of Jiahu’s adaptive strength. The surge in population expanded the workforce. Greater specialization improved efficiency. Together, these changes may have helped the settlement secure food and navigate the challenges imposed by cooling and drought.

After the Storm, a Deliberate Rebalancing

When the 8.2 ka event eased, Jiahu did not simply revert to its earlier way of life. Phase III shows another shift. Burials decreased to 182, and grave goods became less common. The archaeological evidence suggests a conscious reorganization after the crisis passed.

This was not the end of change, but a recalibration. Jiahu had innovated and transformed to survive the climatic shock, and once conditions stabilized, it adjusted again. The community demonstrated flexibility, not rigidity, in the face of environmental uncertainty.

Yet resilience, the study reminds us, does not mean invincibility.

The Floods That Finally Changed Everything

Jiahu’s eventual decline came not during the 8.2 ka event itself, but later. According to Dr. Tan, “After Phase III, the Jiahu settlement faced frequent climatic fluctuations, which further triggered flooding and finally led to the decline of the Jiahu culture. Since the floods completely changed the structure of their habitat, the settlements were no longer functional when the floods hit.”

This distinction is crucial. The same community that adapted successfully to one climatic crisis could not withstand a different kind of environmental transformation. Flooding altered the landscape so fundamentally that the settlement’s structure and way of life were no longer viable.

Resilience, the study shows, is always context-dependent.

Why This Story Matters Today

The story of Jiahu reframes how we think about ancient climate crises. Rather than viewing past societies as passive victims of environmental change, this research highlights their capacity for agency, innovation, and adaptation. Even under abrupt and severe climatic stress, communities could reorganize their social structures, redistribute labor, and draw strength from cooperation.

Equally important is the methodological contribution. By adapting the BRIC model to archaeological evidence, the study demonstrates that tools from modern disaster research can be meaningfully applied to deep history. This opens the door to more structured and comparable studies of resilience across different ancient societies.

In a world increasingly shaped by climate uncertainty, Jiahu’s story resonates beyond the distant past. It reminds us that survival is not only about enduring hardship, but about how communities respond, reorganize, and transform when the environment changes around them.

More information: Yunchen Tan et al, Cultural responses to the 8.2 ka climatic event in North China: Insights from the Jiahu archaeological site, Quaternary Environments and Humans (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.qeh.2025.100092