On a moonless night in late May 1543, shadows moved through the Native American town of Guachoya. A small group of weary Spanish soldiers stopped at a freshly dug grave, their breath sharp in the cool air. They worked quickly and in silence, exhuming the body of their fallen leader — Hernando de Soto, the man who had led them across thousands of miles of uncharted territory.

De Soto had claimed to be a god to the Indigenous people he encountered. But when an unknown illness claimed his life, the illusion crumbled. Fearful of what would happen if the truth spread, his men wrapped his corpse in shawls filled with sand and lowered it into a tributary of the Mississippi River, the water swallowing both the body and the myth.

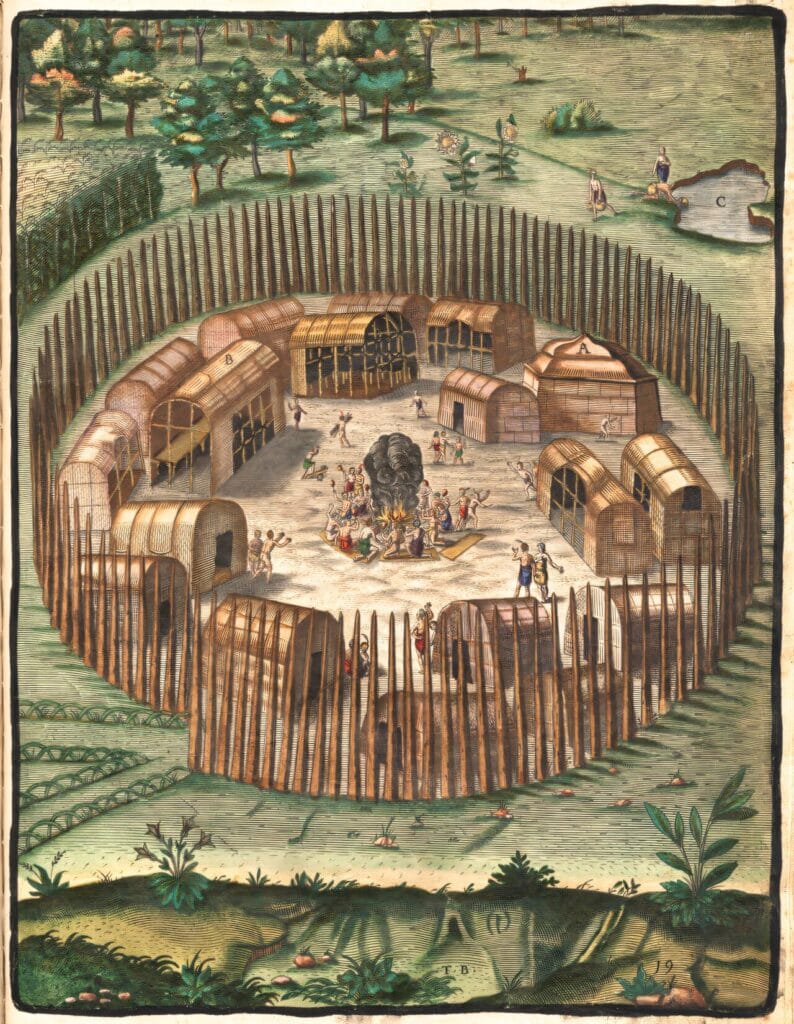

Thus ended the life of the man who had helped conquer Nicaragua, overthrown the Inca Empire in Peru, and led one of the longest, most brutal European incursions into North America. His expedition carved a path from present-day Florida to South Carolina, across the Mississippi, and into Arkansas — leaving a trail of violence, disease, and cultural upheaval.

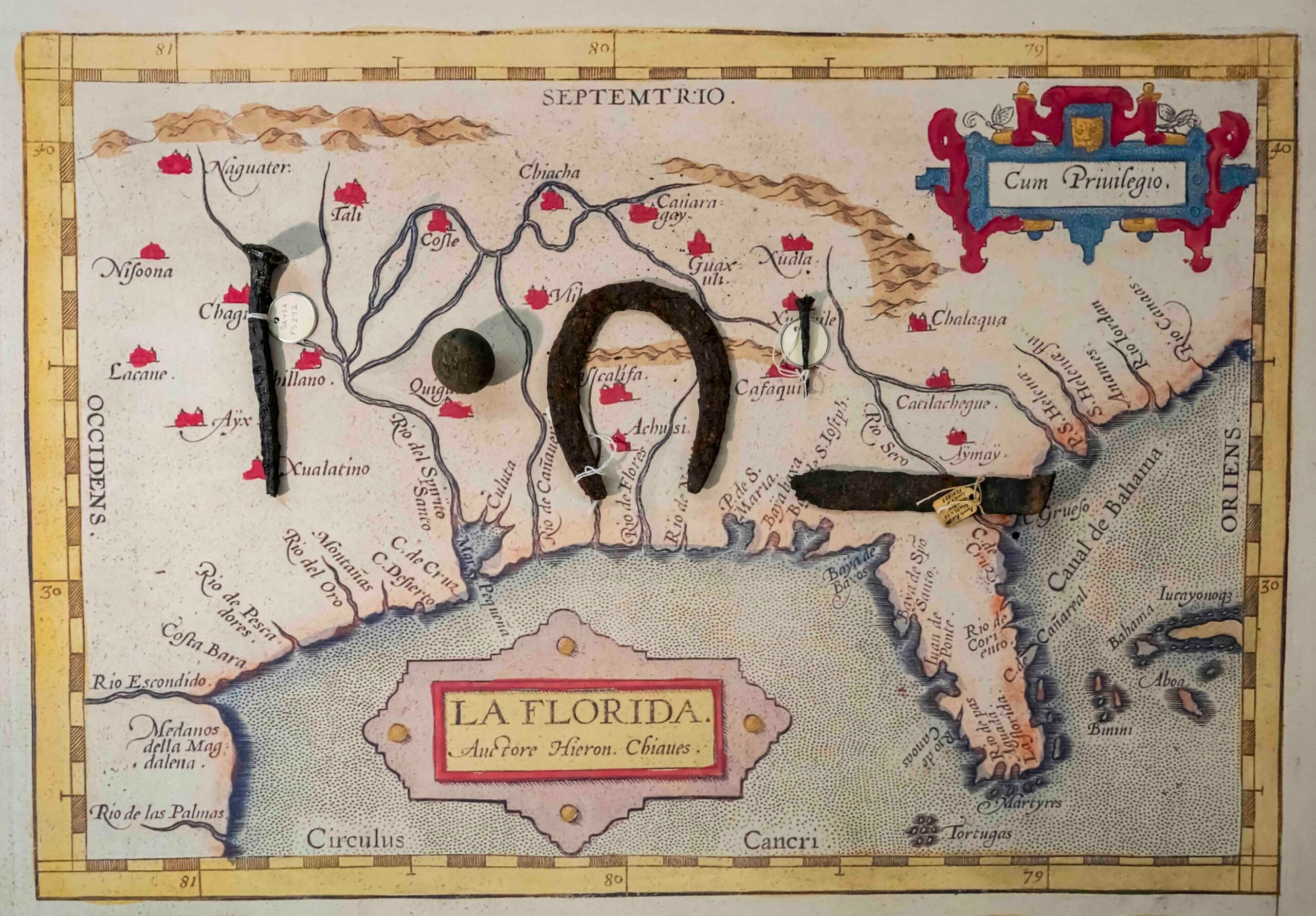

But while Spanish chronicles describe these journeys in great detail, they are vague about the geography. For centuries, historians and archaeologists have debated the exact routes taken by de Soto and other early Spanish explorers. The problem is that their footprints are difficult to trace — especially when the tools and weapons they carried were nearly indistinguishable from those used decades later.

The Problem with Rusty Nails

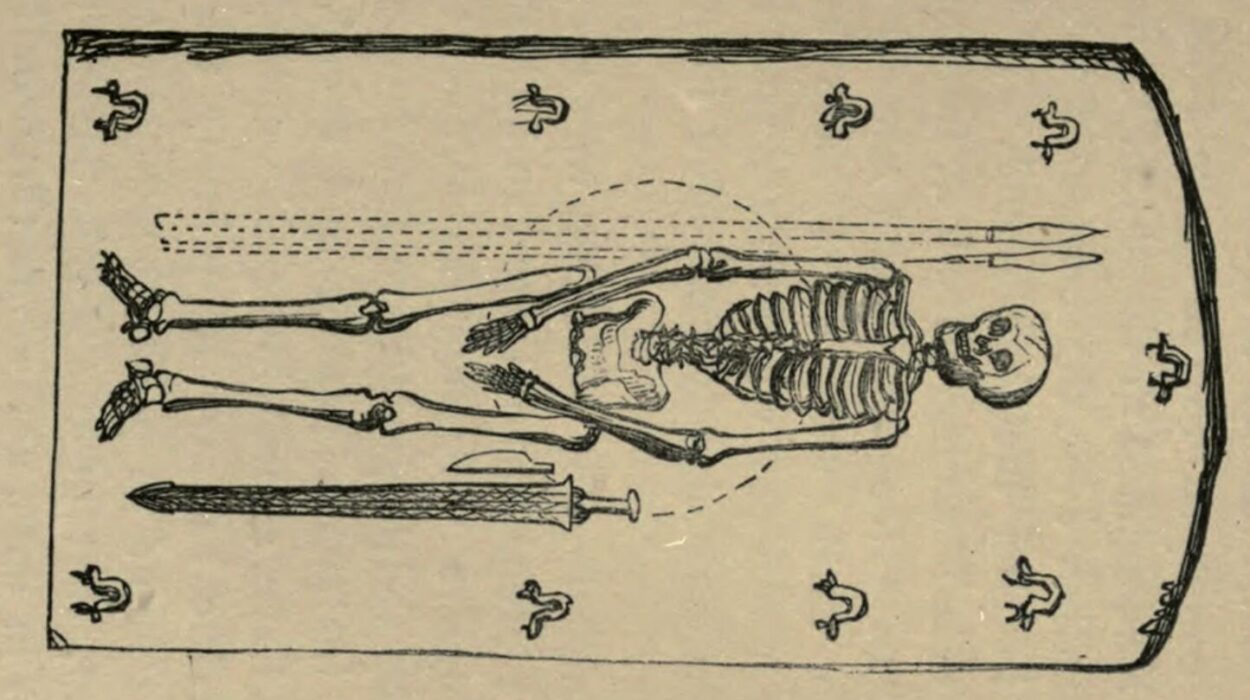

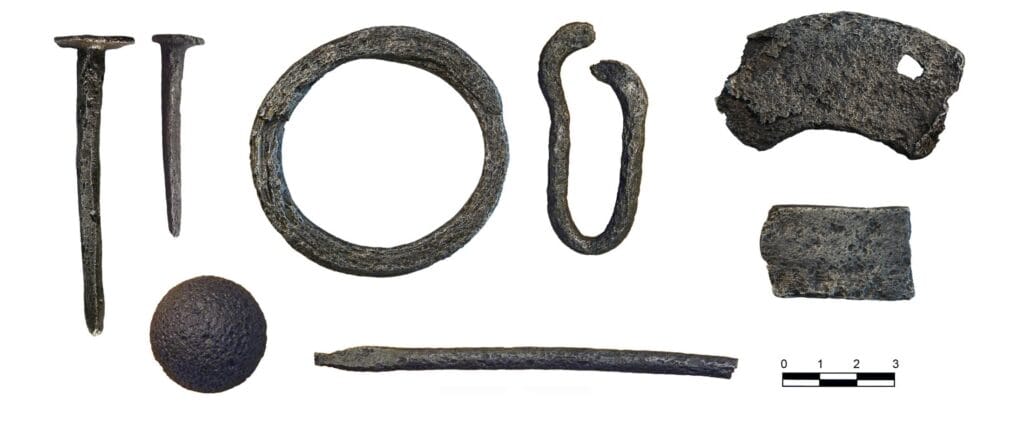

Iron was the lifeblood of Spanish expeditions. Nails, horseshoes, breastplates, spearheads, helmets, and ax blades filled their ships. They even brought blacksmiths to repair and repurpose metal on the march. But over time, these artifacts rust, corrode, and lose the distinctive marks of their origins.

“A wrought-iron nail from the 1500s looks like a wrought-iron nail from the 1600s,” explained Charles Cobb, Lockwood Chair in Historical Archaeology at the Florida Museum of Natural History.

This makes things tricky for archaeologists. Nails make up more than half of all metal artifacts found in historic sites, yet most are catalogued, weighed, and stored without further study. “We often can’t even tell what they are,” said Lindsay Bloch, principal investigator at Tempered Archaeological Services. “So they get put back in the bag — and usually no one ever looks at them again.”

That may be about to change.

A New Way to Read the Past

Cobb and Bloch are co-authors of a groundbreaking new study, published in the International Journal of Historical Archaeology, that uses X-ray fluorescence spectrometry to detect microscopic differences in the elemental composition of iron artifacts. These differences — trace impurities like manganese, bismuth, titanium, and vanadium — can act as a chemical fingerprint, revealing not only the time period in which an object was forged but possibly even where the iron ore was mined.

This approach could finally separate artifacts from different expeditions that passed through the same places, sometimes just years apart. For example, the Marengo complex in Alabama has long puzzled archaeologists. De Soto fought a devastating battle nearby and abandoned supplies in 1540. But two decades later, another Spanish force under Tristán de Luna also passed through, leaving behind similar equipment. Without a way to tell the artifacts apart, their stories have remained tangled — until now.

How Custer’s Last Stand Changed Archaeology

The X-ray method builds on another technological shift in archaeology: the cautious acceptance of metal detectors. For decades, professional archaeologists shunned them, associating the devices with looters and treasure hunters.

That changed in 1983, when a wildfire at the site of the Battle of Little Bighorn cleared the land. Faced with a vast search area, archaeologists used metal detectors to recover munitions and map troop movements. The results were so compelling that metal detection slowly began to earn respect as a legitimate archaeological tool.

Cobb embraced the technology fully. In 2015, while surveying for Chickasaw heritage sites in Mississippi, his team decided to try metal detectors on a hunch. Instead of a few scattered finds, they stumbled upon what may be the long-lost site of a major battle between de Soto’s forces and the Chickasaw — a discovery decades in the making.

Reading the Signature of Spanish Iron

To test their new method, Cobb and Bloch analyzed iron artifacts from a wide range of sites: Columbus’s first colony in the Caribbean, Spanish missions, colonial capitals, battlefields, British forts, and 19th-century plantations.

They found clear patterns. Sixteenth-century iron often contained small amounts of manganese, which was rare in later centuries. Bismuth was common in 18th- and 19th-century artifacts but absent in earlier ones. Other elements, such as titanium, ruthenium, and zirconium, appeared in specific concentrations in late 16th- and early 17th-century objects.

They also noticed that iron from the earliest expeditions was purer overall, especially horseshoes, which had the highest iron content. Quality dipped in the late 1500s and 1600s, possibly reflecting changes in production methods or the sources of ore, before improving again in later centuries.

Preliminary results suggest that much of the iron from the Marengo complex matches the chemical profile of de Soto-era artifacts — a tantalizing clue that could place the site firmly in the story of his expedition.

What Comes Next

X-ray fluorescence spectrometry is fast and non-destructive, but it is just the beginning. To confirm their findings, Cobb and Bloch hope to use isotopic analysis, a more precise — and more expensive — technique that can pinpoint the geographic origin of iron ore.

If successful, this approach could rewrite parts of early American history, linking anonymous rusty nails and corroded horseshoes to specific moments, places, and people. For sites like Marengo, it could mean finally untangling the legacies of multiple expeditions and giving voice to the Indigenous communities who experienced them firsthand.

In the quiet details of rust and metal, the past is speaking again — and thanks to science, we may finally understand what it’s been trying to say for nearly five centuries.

More information: Lindsay Bloch et al, Spanish Signatures? XRF Analysis of Iron Artifacts in the American Southeast, International Journal of Historical Archaeology (2025). DOI: 10.1007/s10761-025-00796-4