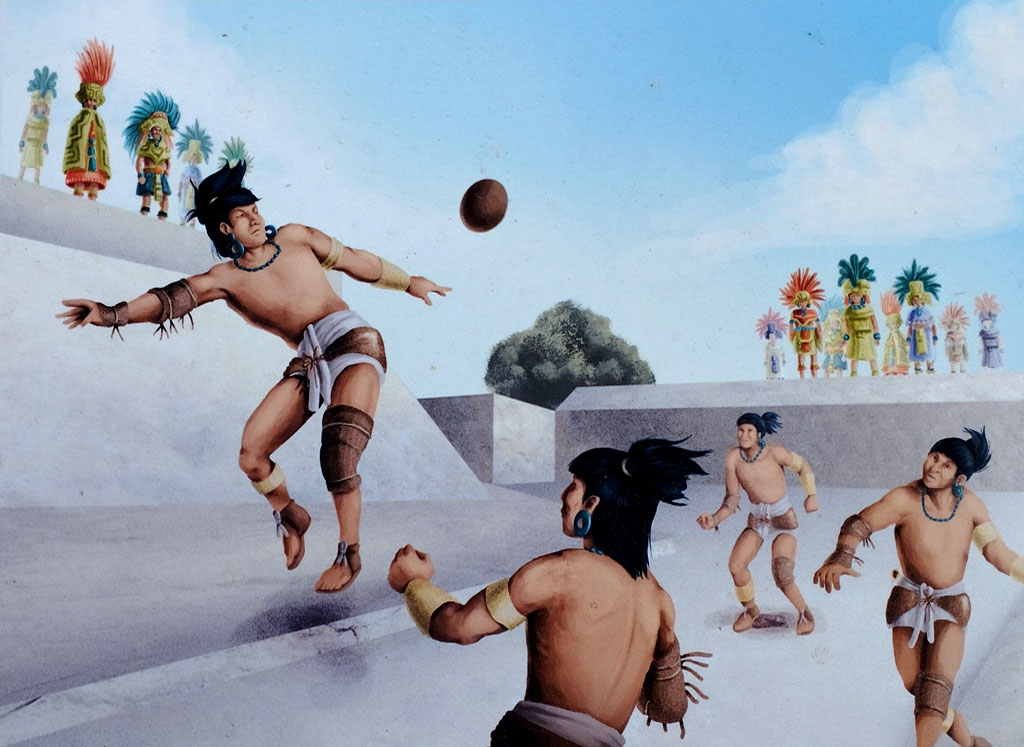

Thousands of years ago, long before soccer stadiums or basketball courts filled with cheering crowds, the people of Mesoamerica gathered in grand stone arenas to watch a game unlike any other. The air was heavy with incense, music echoed through the plazas, and the thud of a solid rubber ball against stone walls sent ripples of anticipation through the crowd. This was not merely a sport. It was ritual, myth, politics, and community all bound together in a sacred performance: the Mesoamerican ballgame.

For the Maya, the Aztecs, and many other civilizations across ancient Mexico and Central America, the ballgame was far more than entertainment. It was a connection to the gods, a symbol of cosmic struggle, and a powerful instrument of political theater. To play was to participate in a drama of life and death, one that reflected the eternal conflict between light and darkness, order and chaos, fertility and barrenness.

The game was physically demanding, socially unifying, and spiritually profound. At times, it was a joyous celebration of athleticism. At other times, it was deadly serious, with players—or even captives—sacrificed in ceremonies tied to cosmic renewal. To truly understand the ancient Mesoamerican ballgame is to peer into a civilization’s soul, where sport and spirituality merged seamlessly into one.

Origins Lost in Deep Time

The roots of the Mesoamerican ballgame stretch back nearly 3,500 years, making it one of the oldest known team sports in the world. Archaeologists have uncovered evidence of ball courts dating as far back as 1650 BCE, in the Olmec heartlands along the Gulf Coast of Mexico. The Olmecs, often called the “mother culture” of Mesoamerica, carved massive stone heads of warriors and rulers, but they also left behind rubber balls, ballplayer figurines, and early courts that point to the game’s central role in their society.

From these beginnings, the ballgame spread across Mesoamerica like wildfire. The Zapotecs of Monte Albán, the Maya of the Yucatán, the Mixtecs of Oaxaca, and the Aztecs of central Mexico all adopted and adapted the sport. Each culture gave it its own flavor, but the essence of the game—the combination of athletic contest and spiritual ritual—remained constant.

By the height of Mesoamerican civilization, ballcourts could be found in nearly every major city, from the great Maya center of Chichén Itzá to the sprawling Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán. More than 1,500 ballcourts have been identified by archaeologists, a testament to the sport’s extraordinary reach and importance.

The Ballcourts: Arenas of Stone and Spirit

To step into a Mesoamerican ballcourt was to enter a sacred space. Unlike the rectangular playing fields of modern sports, these courts were shaped like elongated “I”s, flanked by high stone walls that often sloped inward. The courts varied in size—some small and intimate, others vast and imposing—but their purpose was always both practical and symbolic.

At Chichén Itzá, the largest known ballcourt measures an astonishing 168 meters long and 70 meters wide, large enough to hold thousands of spectators. Its walls are decorated with carved reliefs depicting ballplayers in elaborate costumes and, in some cases, scenes of human sacrifice. When a player struck the ball and it echoed against the stone, the sound would have resonated through the crowd, magnified by the acoustics of the court.

These courts were more than arenas; they were stages where myth and reality intertwined. Many were aligned with celestial movements, reflecting the deep connection between the ballgame and cosmic cycles. The court itself symbolized the universe—a liminal space where the earthly and the divine could meet.

The Ball: A Heavy Sphere of Life

The heart of the game was the ball itself, a dense sphere of solid rubber. Unlike modern balls filled with air, these were heavy, weighing anywhere between 3 and 9 pounds. They could bounce with surprising force, a property that must have seemed magical to the ancient peoples who first discovered the potential of rubber from the latex of native plants.

Handling such a ball was no small feat. Players were forbidden to use their hands or feet; instead, they struck the ball with their hips, thighs, or upper arms. Imagine the strength, skill, and endurance required to keep a solid rubber ball in motion this way for hours. A single misstep could mean a bruised rib, a shattered bone, or worse.

The ball was more than equipment—it was a sacred symbol. In Maya mythology, the ball often represented the sun itself, its motion across the court echoing the sun’s journey across the sky. In some traditions, it also symbolized fertility, maize, or even human life, making every bounce an act of cosmic significance.

The Rules: Between Sport and Ritual

The rules of the Mesoamerican ballgame were not uniform; they varied across time and place. But at its core, the game involved two opposing teams trying to keep the rubber ball in play and, in some cases, pass it through a stone ring set high on the court walls.

Scoring through the ring was a rare and extraordinary feat, given that the openings were small and positioned meters above the ground. More often, points were scored by keeping the ball in motion, with penalties assigned if it touched the ground or was struck improperly.

Yet the precise rules mattered less than the ritual performance. The act of playing itself was sacred. The movement of the ball mirrored the movement of celestial bodies, while the struggles of the players embodied mythological battles between gods and forces of nature. Winning or losing could carry symbolic weight, tied to fertility, warfare, or the favor of the gods.

Ritual and Sacrifice: The Sacred Stakes

Perhaps the most controversial and fascinating aspect of the ballgame was its connection to ritual sacrifice. Carvings at places like Chichén Itzá depict decapitated ballplayers, their blood transforming into serpents or flowing as offerings to the gods. Spanish chroniclers wrote of captives being forced to play, with the losers—or sometimes the winners—sacrificed afterward.

To modern sensibilities, this may seem brutal. But for the peoples of Mesoamerica, sacrifice was not senseless violence—it was a profound act of cosmic renewal. Life and death were intertwined, and human blood was seen as a sacred substance that nourished the gods and sustained the cycles of the universe.

When ballgames culminated in sacrifice, they transformed sport into sacred drama. The players became living embodiments of myth, reenacting the eternal struggle between light and darkness, life and death. The sacrifice ensured the continuation of cosmic order, aligning human society with the rhythms of the divine.

The Ballgame in Myth and Legend

The mythological roots of the ballgame run deep, most famously in the Maya Popol Vuh, a sacred text that preserves the stories of creation and the exploits of the Hero Twins, Hunahpu and Xbalanque.

In the Popol Vuh, the Hero Twins are summoned to the underworld by the lords of death, who challenge them to a ballgame. Through cunning and resilience, the twins defeat the underworld gods, eventually rising to become the sun and the moon. This myth weaves the ballgame into the very fabric of cosmic order: the ballcourt becomes the underworld, the ball the sun, and the players the forces of life struggling against death.

Every game played in a Mesoamerican court echoed this myth. Spectators were not just watching athletes—they were witnessing a reenactment of the universe’s eternal battles. The myths gave the game layers of meaning, turning each contest into a sacred drama with cosmic implications.

Politics and Power: The Ballgame as Theater

Beyond myth and ritual, the ballgame also played a powerful political role. Rulers used it to display their strength, resolve conflicts, or humiliate rivals. Victories on the court could symbolize dominance in warfare or diplomacy, while defeats could undermine a leader’s prestige.

In some cases, rulers staged elaborate games with captives, turning the court into a stage for political theater. The game allowed leaders to demonstrate not only athletic skill but also their connection to divine power. To control the ballgame was to control the narrative of order and legitimacy in society.

The game thus united communities but also reinforced hierarchies. While common people might play in smaller, local courts, the grand spectacles in major cities were orchestrated by elites, blending entertainment, religion, and politics into one seamless performance.

Everyday Play: Beyond the Sacred

It would be a mistake, however, to think of the ballgame only as a grim ritual or elite spectacle. Archaeological and artistic evidence suggests that ordinary people also played for recreation and training. Children had smaller versions of the ball, and some communities may have used the game to settle disputes without bloodshed.

The ballgame was woven into the daily life of Mesoamerican societies. It was played at festivals, market days, and local gatherings, providing both entertainment and a sense of shared identity. The same game could be joyous sport, sacred ritual, and political tool, depending on the context.

The Spanish Encounter and the Game’s Decline

When Spanish conquistadors arrived in the early 16th century, they were astonished by the ballgame. They described the speed, intensity, and spectacle with a mix of fascination and unease. They marveled at the bouncing rubber ball, unfamiliar in Europe, but recoiled at the ritual sacrifices sometimes associated with the sport.

The Spanish viewed the ballgame’s religious dimensions as pagan and sought to suppress it, along with other indigenous rituals. Over time, the grand ceremonial games faded, though local versions survived in some communities. Today, a modern descendant known as ulama is still played in parts of Mexico, preserving a link to the ancient past.

Archaeological Discoveries and Modern Insights

Our understanding of the ballgame continues to evolve with each archaeological discovery. Ballcourts uncovered in remote sites reveal just how widespread the game was. Artifacts, murals, and inscriptions provide glimpses into the players’ attire, the role of spectators, and the symbolic weight of the sport.

The study of the ballgame has also shed light on the cultural interconnectedness of Mesoamerica. From the Gulf Coast to the highlands of Guatemala, the game served as a common thread, linking diverse peoples in a shared tradition. It is a reminder that sport, ritual, and community have always been central to human civilization.

Legacy of the Ancient Ballgame

Though the Mesoamerican ballgame declined after the Spanish conquest, its echoes remain strong. In modern times, it has become a powerful symbol of indigenous heritage, cultural pride, and resilience. Festivals and reenactments bring the game back to life, reminding new generations of its significance.

The ballgame’s legacy also lives on in the global passion for sport. The idea that a game can carry deep cultural, spiritual, and political meaning is something we still recognize today. Modern sports inspire national pride, political statements, and even moments of transcendence. The ancient ballgame reminds us that the line between sport and ritual has always been thin, and that play is one of humanity’s most profound expressions.

Conclusion: A Game Larger Than Life

The ancient Mesoamerican ballgame was never just a pastime. It was a ritual of life and death, a performance of myth, a tool of politics, and a celebration of community. It asked players to risk their bodies, sometimes even their lives, in service of something larger than themselves: the maintenance of cosmic balance.

To watch a ballgame in the plazas of Chichén Itzá or the streets of Tenochtitlán was to witness the universe in motion. Every bounce of the ball echoed the sun across the sky, every contest mirrored the struggles of gods and men. It was a game, yes—but also a prayer, a spectacle, and a reminder of humanity’s deep connection to the cycles of life and death.

Even now, centuries later, the story of the ballgame continues to resonate. It reminds us that sport is never only about winning or losing. It is about meaning, identity, and the search for transcendence. In the heavy bounce of a rubber ball on stone, the ancient peoples of Mesoamerica found the rhythm of the cosmos—and in remembering their game, we rediscover the timeless power of play itself.