In the dense jungles of Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula rises one of the most awe-inspiring remnants of human civilization: Chichen Itza. This sprawling ancient city, once the heartbeat of Mayan culture, stands as both a scientific marvel and a haunting reminder of humanity’s enduring quest for knowledge, power, and connection with the cosmos. The name Chichen Itza means “at the mouth of the well of the Itza,” a poetic nod to the city’s relationship with sacred water sources that sustained its people both physically and spiritually.

Walking among the weathered stones of Chichen Itza is like stepping into two worlds at once: one of silent ruins draped in the stillness of centuries, and another alive with echoes of ancient rituals, bustling marketplaces, and the deep hum of sacred ceremonies. Here, pyramids align with the stars, temples whisper of forgotten gods, and ball courts once rang with the intensity of a game that was more than sport—it was a bridge between life and death.

Chichen Itza is not merely an archaeological site. It is a story carved in stone, a dialogue between humanity and the universe, and one of the great wonders of the ancient world.

The Origins of Chichen Itza

The roots of Chichen Itza stretch back to the Early Classic period of Mayan civilization, around the 5th century CE, though its most flourishing period came much later, between the 9th and 12th centuries. This was a time of political upheaval across Mesoamerica, and Chichen Itza rose to prominence as a dominant power in the Yucatán.

The Itza people, a Mayan ethnic group whose name may derive from “water magicians,” are believed to have founded the city. Strategically positioned near cenotes—natural sinkholes filled with fresh water—Chichen Itza became both a place of survival and of reverence. Water in the Yucatán was scarce, making cenotes vital lifelines. Yet for the Maya, these cenotes were also portals to the underworld, places where offerings, sacrifices, and prayers could reach the gods.

Over time, Chichen Itza grew into a multicultural hub, blending Mayan traditions with influences from central Mexico, particularly the Toltecs. This fusion is evident in its architecture, art, and religious practices, making the city a vibrant crossroads of ideas and beliefs.

The Sacred Geography of the City

Chichen Itza was not built haphazardly. Its layout reflects careful planning rooted in cosmology, mathematics, and astronomy. At its core stands the Pyramid of Kukulcán, also known as El Castillo, a temple dedicated to the feathered serpent deity. Around it spread vast plazas, temples, palaces, and ball courts, all aligned with celestial cycles and symbolic meanings.

The city’s structures reveal a deep understanding of astronomy. Alignments with equinoxes, solstices, and planetary movements suggest that Chichen Itza was as much an astronomical observatory as it was a political and religious center. To walk its grounds is to realize that this was not just a city of stone—it was a city of stars.

El Castillo: The Pyramid of Kukulcán

At the heart of Chichen Itza towers El Castillo, the Pyramid of Kukulcán, a monument that captures the essence of Mayan genius. Rising nearly 30 meters into the sky, the pyramid dominates the central plaza with a grace that belies its massiveness. But this structure is more than a pyramid—it is a calendar written in stone.

Each of the pyramid’s four sides contains 91 steps. When added together, including the top platform, the total is 365—the exact number of days in a solar year. Twice a year, during the spring and autumn equinoxes, a breathtaking phenomenon occurs. As the sun sets, shadows cast by the pyramid create the illusion of a serpent slithering down the staircase, merging with the carved serpent heads at the base. This spectacle symbolized the descent of Kukulcán, the feathered serpent god, blessing the city and its people.

The pyramid is not only a religious symbol but also a testament to the Mayans’ mastery of mathematics, astronomy, and architecture. It reminds us that for the Maya, science and spirituality were inseparable—both paths toward understanding their place in the universe.

The Great Ball Court: Arena of the Gods

To the northwest of El Castillo lies the Great Ball Court, the largest and most magnificent of its kind in Mesoamerica. Measuring 168 meters long and 70 meters wide, with towering walls and ornately carved panels, this court was the stage for the sacred ballgame known as pok-ta-pok.

The game was more than a sport; it was a ritual that symbolized cosmic struggles—light versus darkness, life versus death. Players used their hips to strike a heavy rubber ball through stone rings mounted high on the walls. The stakes were monumental. Some evidence suggests that the game’s outcome determined matters of war, politics, or even sacrifice.

Carvings on the ball court’s walls depict decapitation, hinting that losing players—or sometimes the winners—were offered to the gods. To modern minds, this may seem brutal, but for the Maya, sacrifice was the ultimate gift, a way to ensure cosmic balance and sustain the cycle of life.

The echoes of the ballgame still linger in the court’s acoustics. A clap of the hands reverberates across the stone walls, amplifying the sound in a way that feels otherworldly. It is as if the voices of the past still play within those walls, forever bound to the sacred drama that unfolded there.

The Temple of the Warriors and the Thousand Columns

Another striking feature of Chichen Itza is the Temple of the Warriors, a massive stepped pyramid flanked by rows of carved columns. These columns, often referred to as the “Thousand Columns,” once supported a vast roofed hall where warriors may have gathered for rituals, feasts, or council.

At the temple’s summit sits a Chacmool statue, a reclining figure holding a bowl upon its stomach. Chacmools were associated with offerings, possibly of food, incense, or human hearts. The temple and its surrounding colonnades reflect not only military might but also the blending of Toltec and Mayan cultures. The warrior imagery, with its feathered serpents and jaguar motifs, speaks to a society where religion, warfare, and power were deeply intertwined.

The Sacred Cenote: Portal to the Underworld

Perhaps the most haunting site of Chichen Itza is the Sacred Cenote, a vast sinkhole with sheer limestone walls plunging into deep green waters. For the Maya, this cenote was more than a source of water—it was a direct connection to Xibalba, the underworld.

Archaeological explorations of the cenote have uncovered offerings of gold, jade, pottery, and human remains. Spanish accounts suggest that both men and women were sacrificed here, cast into the waters as offerings to the rain god Chaac. Some may have drowned, while others perhaps survived, retrieved later as part of ritual acts.

The cenote reminds us of the duality of life and death in Mayan belief. Water was life-giving, yet the cenote also symbolized death and rebirth, a sacred threshold where the earthly and divine converged.

Astronomy and the Cosmos

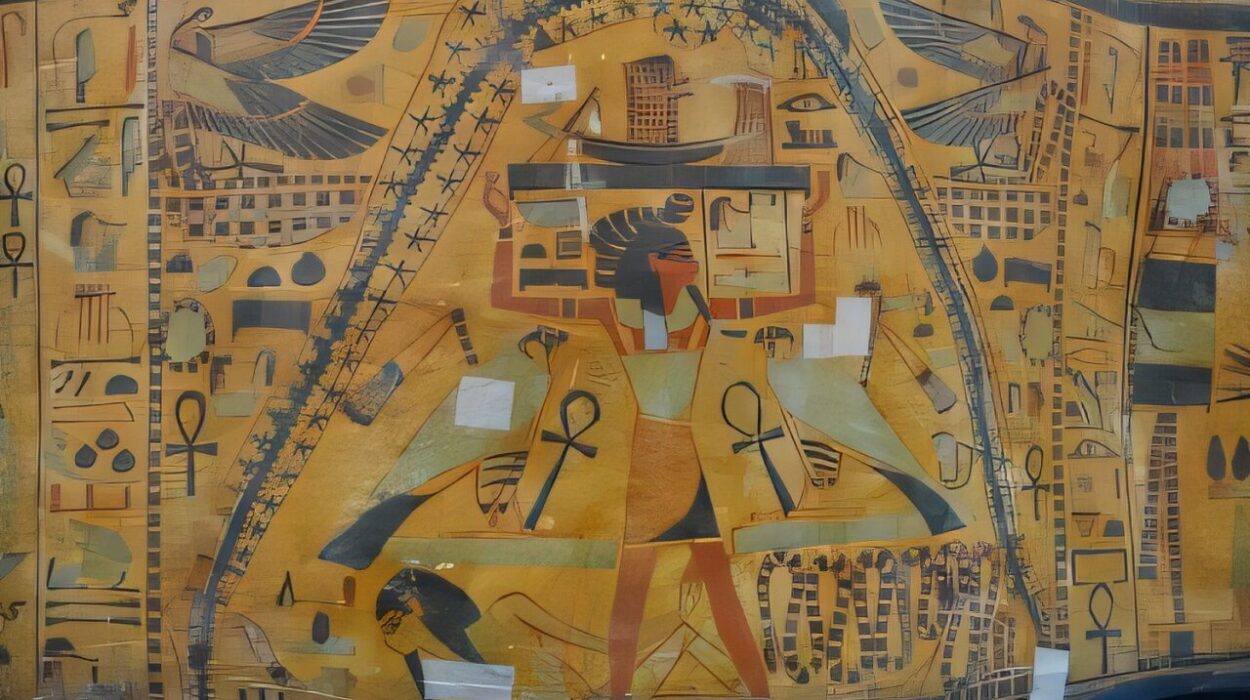

The Maya were extraordinary astronomers, and Chichen Itza bears witness to their cosmic vision. The city’s structures align with celestial events, from the equinox serpent shadow at El Castillo to the circular Caracol observatory, whose windows and platforms track Venus, the moon, and other heavenly bodies.

Venus, in particular, held immense significance for the Maya, often associated with war and prophecy. Alignments within Chichen Itza reveal how closely the Maya observed its cycles, weaving them into their rituals and calendars.

The Caracol, with its spiral staircase and rounded shape, resembles a modern observatory. It reflects the sophistication of a people who charted the skies not only for agricultural purposes but also to understand the rhythms of the universe.

Daily Life in Chichen Itza

While its monumental architecture often takes the spotlight, Chichen Itza was also a living city, home to farmers, artisans, merchants, priests, and rulers. The surrounding areas supported agriculture through advanced techniques, including raised fields and irrigation systems that maximized crop yields in a challenging environment.

Markets bustled with trade, connecting Chichen Itza to distant regions. Goods such as obsidian, jade, cacao, salt, and feathers flowed into the city, enriching its economy and cultural diversity. Artisans carved intricate sculptures, painted murals, and produced textiles, leaving behind a legacy of craftsmanship that still astonishes today.

Religious rituals punctuated daily life, from small household ceremonies to grand festivals. Music, dance, and incense filled the plazas, while priests performed rites to honor the gods and ensure prosperity. Life in Chichen Itza was vibrant, complex, and deeply spiritual.

The Decline of Chichen Itza

Like many great cities, Chichen Itza eventually fell into decline. By the 13th century, its political power waned, and other centers rose to prominence. The reasons for its decline are still debated: internal strife, rebellion, resource depletion, climate change, or a combination of these factors may have contributed.

By the time Spanish conquistadors arrived in the 16th century, Chichen Itza had lost much of its former glory, though it remained a site of pilgrimage and reverence for the Maya. Its ruins, swallowed by the jungle, waited centuries to be rediscovered.

Rediscovery and Modern Legacy

In the 19th century, explorers and archaeologists began to uncover Chichen Itza’s secrets, documenting its ruins and sparking fascination worldwide. Excavations revealed its grandeur, while restorations brought structures like El Castillo back to life.

Today, Chichen Itza is recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of the New Seven Wonders of the World. Millions of visitors walk its plazas each year, drawn by its beauty, mystery, and the allure of the Maya.

Yet Chichen Itza is not only a tourist destination—it is a cultural and spiritual touchstone. For modern Maya communities, it remains a place of heritage and identity, a reminder that their ancestors’ wisdom still echoes across time.

The Timeless Wonder of Chichen Itza

Chichen Itza is more than stone ruins; it is a living story. It tells of a people who gazed at the stars and saw gods, who built temples that captured the dance of light and shadow, who played games with the weight of cosmic significance, and who lived, thrived, and sacrificed in pursuit of balance with the universe.

To stand before El Castillo at sunset, to hear the echoes in the ball court, or to peer into the depths of the Sacred Cenote is to feel the weight of centuries and the brilliance of human imagination. Chichen Itza is not just an ancient city—it is a testament to what humanity can achieve when science, art, and spirituality are woven into a single vision of the world.

It is, and will always be, a city of wonders.