High in the rugged folds of the Pyrenees, where icy winds sweep through craggy valleys and mist drapes over the peaks like forgotten veils, a broken building lies cradled in the earth. To the untrained eye, it’s just a pile of stones, a ruin too old to mourn. But beneath this charred skeleton lies a moment, frozen in destruction. A moment when peace turned to terror, when a way of life was shattered by fire.

The place is Tossal de Baltarga, a hilltop settlement once home to the Cerretani—a people who thrived in these mountain valleys during the Iron Age. It was a community with no need for walls. Its perch gave it strength. From here, the locals watched over river crossings and trade routes, threading through the mountains like lifelines.

But the fires that consumed Tossal de Baltarga were not kindled by accident. They were not born of cooking flames or hearthside embers. They were fierce, total, and coldly deliberate.

And they may have come in the wake of war—specifically, the Second Punic War, when Hannibal, the great Carthaginian general, crossed the Pyrenees with his war elephants and troops, leaving more than just footprints in his path.

A Gold Earring in the Ashes

Dr. Oriol Olesti Vila of the Autonomous University of Barcelona leads the team that uncovered the tragedy buried beneath centuries of soil and silence. Their work at Building G, part of the larger Tossal de Baltarga site, revealed a devastating scene: two floors, collapsed into a blackened heap. Wood, once beams and rafters, burned so hot it turned to dust. The lives that once animated this structure were gone, but their stories lingered in the ruins.

Among the ashes, nestled in a small ceramic vessel, lay a delicate gold earring—still gleaming faintly, untouched by the inferno. It was not merely jewelry. It was a whisper of fear. A keepsake hidden in haste. The kind of thing you bury when you think you might not return. When you hope to come back but know, deep down, you probably won’t.

Not far from the earring lay a pickaxe of iron, a tool of labor and survival. These weren’t riches; they were fragments of a life suddenly disrupted. The survival of these items, spared by chance or by fire’s curious selectiveness, gave voice to a vanished household.

When the Sky Fell Indoors

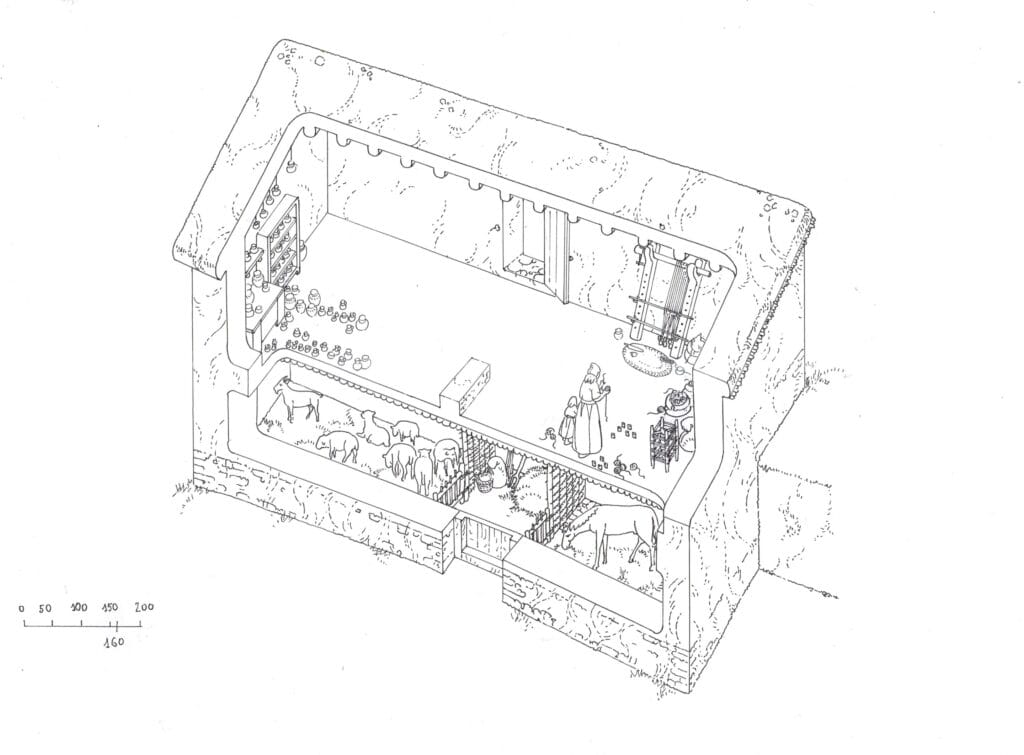

The house, like many others at the site, had been built with care. Its two floors served both human and animal needs. The upper story had been a hive of domestic activity—evidence of cooking, textile work, and food storage was scattered among the debris. Loom weights and spindle whorls hinted at a culture that spun its own wool, likely sheared from goats and sheep housed on the lower level. Archaeologists found grains—barley and oats—stored and prepared for meals. The clay pots bore the traces of hearty stews, with hints of pork and milk.

This was not a poor family scraping by in isolation. This was a household with structure, rhythm, and access to resources. A family that cooked, wove, raised animals, and likely bartered with neighbors across the valleys.

But then the world tilted.

Fire roared through the settlement. The heat grew so intense that the building’s top floor collapsed onto the one below, sealing in a moment of pure chaos. Wood blackened and twisted. Ceilings fell. And beneath it all, six animals—four sheep, one goat, and a horse—died trapped in their stalls.

They weren’t just left behind. They were enclosed—likely locked in, the door barred by someone expecting to come back.

Echoes of an Invasion

Why did the Cerretani not return? Why was nothing salvaged? The evidence points not to accident, but to sudden violence.

“The destruction was intentional,” said Dr. Olesti Vila. “The fire wasn’t confined to Building G. It consumed the entire site. This was organized, human-inflicted devastation. And it aligns eerily with the historical timeline of Hannibal’s crossing of the Pyrenees during the Second Punic War.”

Around 218 BCE, Hannibal Barca launched one of the most ambitious military campaigns in ancient history. Marching his forces from Iberia toward Italy, he chose to traverse the mountains that stood like a fortress between empires. Roman historians wrote of Hannibal’s conflicts with mountain tribes as he forced his way through. Some of those tribes, Olesti Vila believes, could have included the Cerretani.

Tossal de Baltarga, lacking defensive walls, may have seemed vulnerable. Yet its strategic position over key travel routes made it impossible to ignore. If Hannibal’s men—or perhaps even a hostile tribe in his wake—needed to make a statement, a purge of this settlement would have served as both punishment and warning.

In one of the site’s other buildings, a burned dog’s remains were found. Faithful, perhaps, even unto death.

The Traces Beneath the Ground

Much of what we know about the people of Tossal de Baltarga comes from the things they left behind—unintentionally preserved by the very fire that destroyed them. Burned wood, fallen architecture, cooking tools, and food residues—together, they weave a rich tapestry of daily life on the edge of empire.

The textile production area tells us that these were not only herders, but skilled artisans. The presence of milk residues and pork stews suggests a varied diet, made possible by both livestock and trade. Isotope analysis of some sheep bones even suggests that certain animals had grazed far from the settlement, in lowland pastures—hinting at ties to other communities and economic networks.

“These were not isolated people,” Olesti Vila said. “They were connected—economically, culturally, and politically. The mountain did not cut them off; it positioned them.”

But it may have also exposed them. Their lack of walls, their open interaction with the valleys below, and their location along a major route made them easy targets during times of conflict.

What the Fire Couldn’t Burn

Perhaps most haunting is what the fire did not take: the memory.

Even though no human remains were found in Building G, the story isn’t one of total erasure. Some people must have escaped. In later periods, Tossal de Baltarga was reoccupied—this time by Roman forces. And the reoccupation was strategic. The Romans built defenses where none had existed before, including a watchtower that stood like an eye over the valley.

Someone remembered. Someone carried the tale of what happened on that terrible day—when doors were locked, treasures were buried, and animals were left to perish. Someone passed down the knowledge that this site needed protection if it was to live again.

A Landscape Scarred, A People Remembered

Today, Tossal de Baltarga sits in quiet ruins. The wind hums where laughter once rose, and the stone foundations are all that remain of bustling homes. But thanks to science, archaeology, and the labor of those who listen to the earth, the site has spoken once more.

It tells a story not just of death, but of life—of weaving and cooking, of trade and connection, of gold earrings hidden in fear, and of a horse that stood faithfully until the end. It tells of how global wars ripple into the lives of people far from the battlefields. Of how empire and ambition can scorch even the quietest mountain valleys.

And it reminds us, in ash and silence, that even the smallest ruins carry voices worth hearing.

Reference: The exploitation of mountain natural resources during the Iron Age in the Eastern Pyrenees: the case study of production unit G at Tossal de Baltarga (Bellver de Cerdanya, Lleida, Spain), Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology (2024). DOI: 10.3389/fearc.2024.1347394