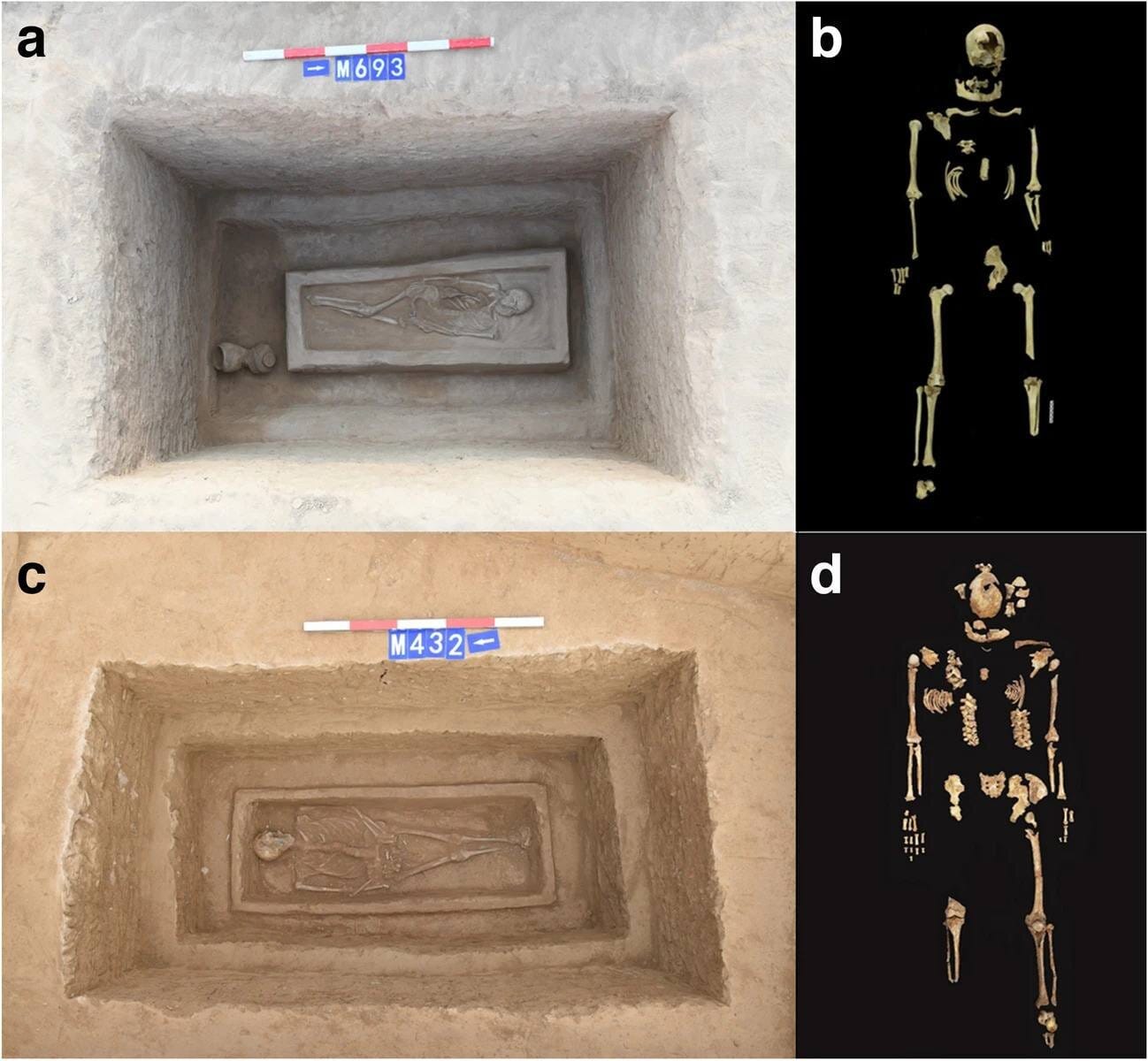

The bones lay silent beneath the earth for over two millennia, yet when they were unearthed, they spoke volumes—of pain, punishment, power, and survival. In the sunbaked soil of Sanmenxia, an ancient city along the Yellow River in northwestern Henan Province, archaeologists found something peculiar: two unrelated skeletons, buried with the dignified trappings of upper-class life, each missing a near-identical portion of a lower leg.

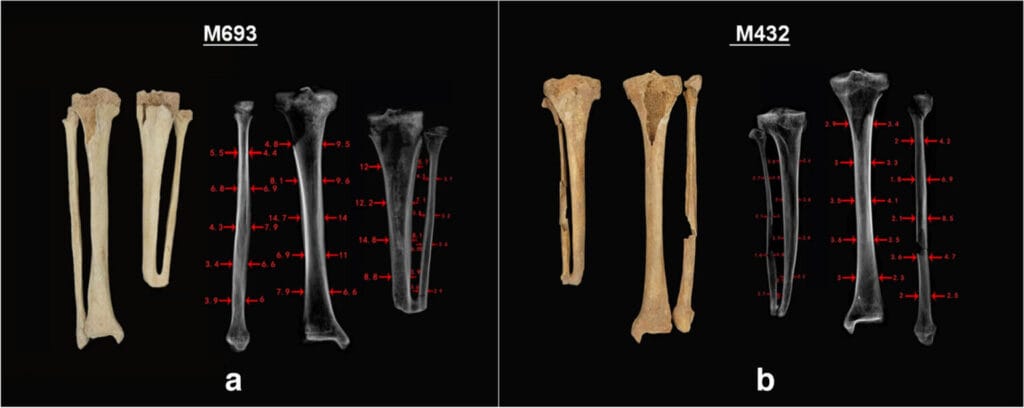

One man lacked approximately one-fifth of his left shin. The other bore the same loss on the right. Down to the centimeter, the amputations were alike. Not the hurried sawing of battlefield trauma or the jagged fractures of an animal attack, but clean, surgical removals—deliberate, purposeful.

What calamity had severed these lives, not at death, but in their living years? It might sound like a scene from a forensic drama, but the clues pointed not toward modern violence, but ancient justice.

Uncovering an Ancient Sentence

The task of decoding this riddle fell to Dr. Qian Wang, a paleoanthropologist and professor at Texas A&M University’s School of Dentistry. His expertise in osteology—the scientific study of bones—enabled him to reconstruct the story hidden in the quiet geometry of these injuries.

Wang’s investigation, conducted in collaboration with scholars in China’s Henan Province and published in Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, centered on a possibility as chilling as it was culturally profound: these two men had been punished under a legal system that used amputation not as medicine, but as justice.

Their injuries bore all the hallmarks of Yue, a form of punitive mutilation practiced during the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (770–256 BCE). More than a simple deterrent, Yue was a calculated act meant to both punish and stigmatize. It was, in many cases, a fate deemed more merciful than execution—but also more visible.

“Based on penal laws of the Zhou Dynasty, Yue, or punitive amputation, was executed in criminal cases including deceiving the monarch, fleeing from duties, stealing, and so on,” Wang explains. “On some occasions, it served as a reduced penalty in lieu of death to reflect leniency.”

These were not crimes judged in haste. The Eastern Zhou legal system was elaborate, a product of a deeply hierarchical and ritual-driven society. Amputation was ranked just below death on the scale of punishment severity, and its impact was not merely physical. It marked a person permanently—socially, morally, and politically.

The Cost of Survival

For the two men in question, the amputations were not instant death sentences. Their bones told another story: of healing, of recovery, of lives that continued. The affected limbs showed signs of advanced bone fusion—a biological indicator that months or even years had passed after the initial surgery.

Curiously, one of the men, the one missing part of his right leg, showed more evidence of disuse atrophy—thinning and weakening of bones due to lack of weight-bearing activity. This detail suggested he lived longer post-amputation, perhaps walking with a crutch, or carried by servants if his status allowed. The other, missing part of his left leg, also survived, but perhaps not as long.

Both were eventually laid to rest with ceremony and care. They were not cast aside or treated as pariahs. Their burials were consistent with people of rank. Two-layered coffins aligned in the north-south orientation typical of nobility, surrounded by grave goods like pottery and stone tablets, spoke of a social world that, despite its harsh codes, offered pathways to redemption and reintegration.

A Justice System of Flesh and Ritual

The Eastern Zhou Dynasty was a time of philosophical ferment and political complexity. Confucianism was being born in these very centuries, with its emphasis on harmony, duty, and ritual. Yet it was also a time of stark social divisions and brutal enforcement of law.

Unlike modern prisons, ancient China used the body as its courtroom and its billboard. Punishment wasn’t hidden—it was carved onto the flesh. The removal of a foot, a nose, or even genitals was not only a personal injury, but a permanent public label.

In the Zhou legal code, different amputations reflected varying degrees of wrongdoing. The left leg might be removed for crimes such as tax evasion or neglecting official duties. The right leg, as in one of these cases, was associated with more serious violations—perhaps fraud against a royal, or failure in military obligations. For even graver offenses, both feet could be taken. It was a calibrated cruelty, a jurisprudence where morality was weighed out in limbs.

Such punishments were not uncommon. Legends abound with famous figures who endured them, including the strategist Sun Bin, whose mutilation did not prevent his rise to greatness. These stories, passed through generations, reflect a cultural tolerance—perhaps even a reverence—for those who suffered visibly but lived honorably.

Healing with Honor

If the penal system was severe, its integration with medical care was surprisingly advanced. Wang notes that in both cases, the amputations show clean cuts and minimal fragmentation—indications of surgical precision rather than battlefield butchery. There is no evidence of infection or chaotic healing.

This suggests the presence of an organized system of post-punishment care. Though amputations were judicial in nature, they were likely performed by trained professionals—possibly early surgeons with knowledge of anatomy and techniques for minimizing pain and blood loss. Pain relief may have come in the form of herbs or alcoholic tinctures, especially for members of the aristocracy, who would have had access to superior care.

In fact, these two men may have been among the fortunate few. Their high status, inferred from their burial treatment, likely granted them not only better recovery options but also social reintegration. In a society governed by ritual, even disgrace could be managed with dignity.

What Tombs Reveal About Status and Survival

To understand who these men were in life, Wang and his colleagues turned to the graves themselves. The Zhou Dynasty’s Way of Rituals prescribed burial practices that mirrored the social hierarchy in excruciating detail. Everything from tomb orientation to the number of coffin layers served as a signal of rank.

In these two cases, both men were buried with double-layered coffins—a privilege reserved for low-level officials or members of the gentry. Commoners typically received single coffins, if any, and were buried facing east-west. The north-south orientation found here was symbolic: the direction of heaven and royalty.

Grave goods provided further clues. Ceramic pots, stone tablets, and other funerary items found with the bodies were typical of elite burials during the Eastern Zhou period. Most compellingly, isotopic analysis of their bones revealed a diet high in protein—more meat, dairy, and legumes than would have been available to the lower classes. Food, in this context, became another testament to privilege.

This convergence of biological, archaeological, and cultural evidence paints a picture of two men who once wielded power, who faced shame, and who managed, against the odds, to retain some measure of their status until death.

From Judgment to Legacy

Punishment by amputation would officially be abolished in 167 BCE, during the reign of Emperor Wendi of the Han Dynasty. The law changed, but not all at once. Evidence of such mutilations continued into later eras, even appearing in the Qing Dynasty thousands of years later. One documented case describes a man whose feet were both sawed off—a grim echo of a much older tradition.

The idioms and legends left behind reflect how deeply this practice penetrated cultural memory. The philosopher Han Feizi once remarked that amputations were so common, it drove down the cost of shoes and raised that of prosthetics. Bian He, the unfortunate courtier who lost both feet after trying to present a genuine jade to a disbelieving king, became a symbol not only of injustice, but of enduring faith in truth.

Through these stories—and through the bones themselves—we glimpse a society where morality, law, and physical integrity were intimately bound.

A Humanity Both Familiar and Alien

What remains most haunting about these two amputated skeletons is not just the pain they endured, but the lives they likely led afterward. In a modern context, such punishment would be seen as barbaric. But in its time, it was part of a deeply moral framework—flawed, perhaps, but coherent within its own logic.

The men survived. They were not discarded. They were buried with care, with status, with the signs of a life lived in full. This suggests something profound: that even within a harsh system, there existed the possibility for recovery, for reconciliation, for honor to be restored.

It is easy to judge ancient practices from the perspective of today, but the real lesson may be more complex. Cultures are not static. They evolve. They remember. They revise. The scar becomes a symbol, and the symbol a story.

Dr. Wang’s work offers not just a glimpse into the mechanics of ancient punishment, but a meditation on justice itself—its brutality, its contradictions, its strange capacity to both destroy and preserve.

In the end, the bones speak not of violence alone, but of resilience. And in that resilience, we find something enduringly human.

Reference: Yawei Zhou et al, Surviving punishment by body reduction in a hierarchical society: A bioarcheological study of two punitive amputation cases in Eastern Zhou Dynasty (771–256 BCE) with references to the penal and medical systems of ancient China, Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences (2024). DOI: 10.1007/s12520-024-01961-2