In the soft crook of the Tamiš River in northeastern Serbia, a quiet piece of earth has whispered a 7,000-year-old secret. Beneath layers of soil, season, and silence, a vast Neolithic settlement has come to light—its outline revealed not through excavation but through magnetism and mathematics. Here, just outside the modern village of Jarkovac in Vojvodina, ancient lives once played out in a network of ditches, homes, rituals, and quiet revolutions.

This was no ordinary discovery. In a region where traces of the Late Neolithic are rare and fragmentary, the sheer size of this site—spanning 11 to 13 hectares—has stunned archaeologists. “This discovery is of outstanding importance,” says Professor Dr. Martin Furholt of Kiel University, who leads the ROOTS Cluster of Excellence team. “Hardly any larger Late Neolithic settlements are known in the Serbian Banat region.”

To understand the significance of what has been found here, one must first appreciate what the Neolithic really was. It was a moment when humans, scattered for millennia in small, mobile bands, began to anchor themselves to the land. They built homes of wood and clay, they grew wheat and millet, they kept pigs and cattle. They also began to think about property, about division, about inheritance. This is where the foundations of inequality were first stirred in the sediment of civilization.

The Earth Reveals Its Geometry

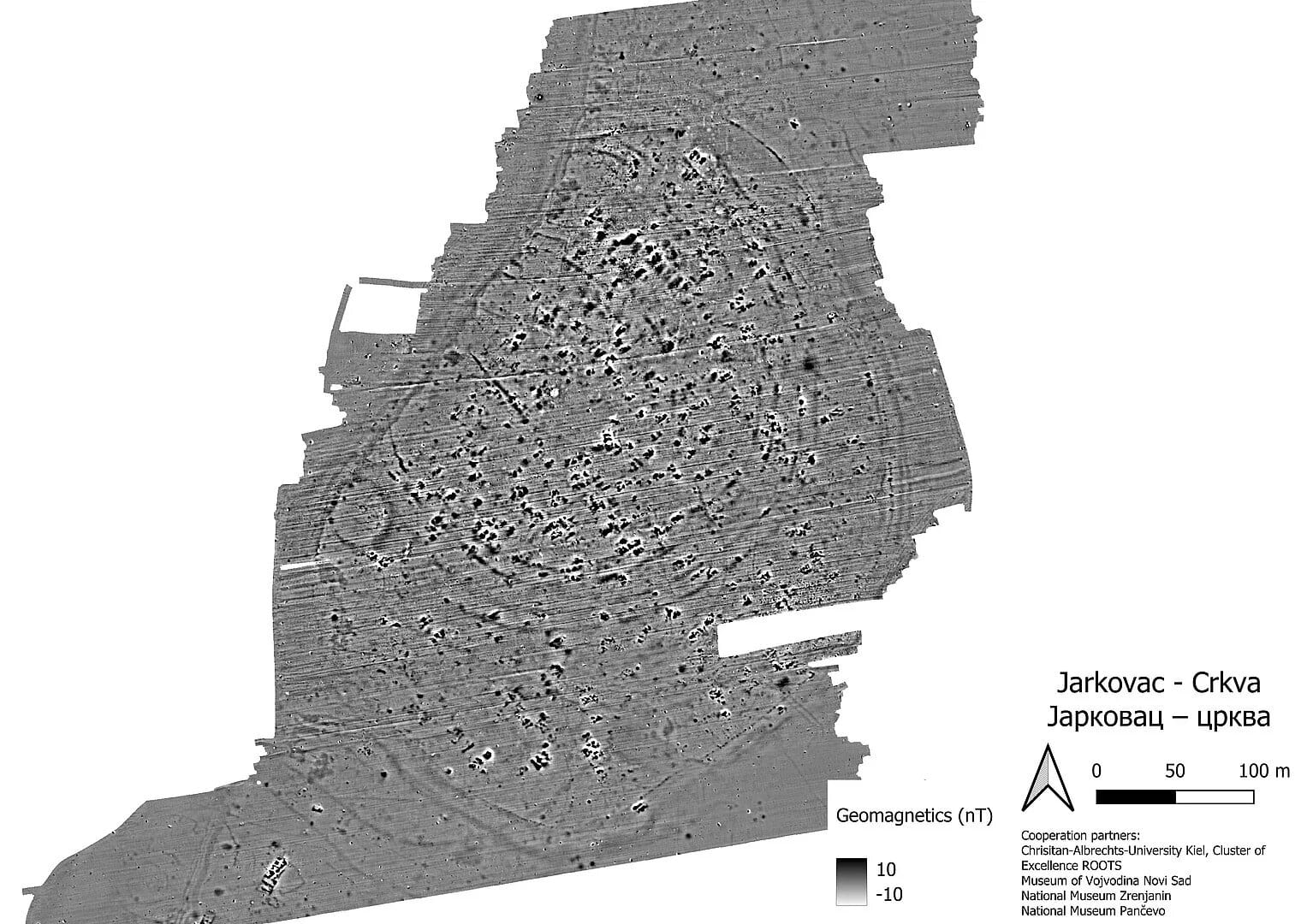

Unlike the drama of digging up golden relics or standing stones, this Neolithic city came into view through the quiet pulse of geophysics. In March, using magnetometers and other survey tools, the German-Serbian research team traced the faint but unmistakable imprint of humanity on the land. Long before modern mapping apps, these Neolithic people had organized themselves with striking complexity: their settlement encircled by four to six concentric ditches—neither chaotic nor incidental, but deliberate and planned.

“A settlement of this size is spectacular,” says Fynn Wilkes, a ROOTS doctoral student and co-leader of the survey. “The geophysical data gives us a clear idea of the structure of the site 7,000 years ago.”

To the trained eye, these ditches tell a story far richer than defense alone. They hint at social boundaries—who was inside, who stayed out. They could signify spiritual enclosures, ceremonial perimeters, or the architecture of early inequality. In a world without stone walls or government, ditches could draw lines not just through earth, but through society.

The Vinča-Banat Mosaic

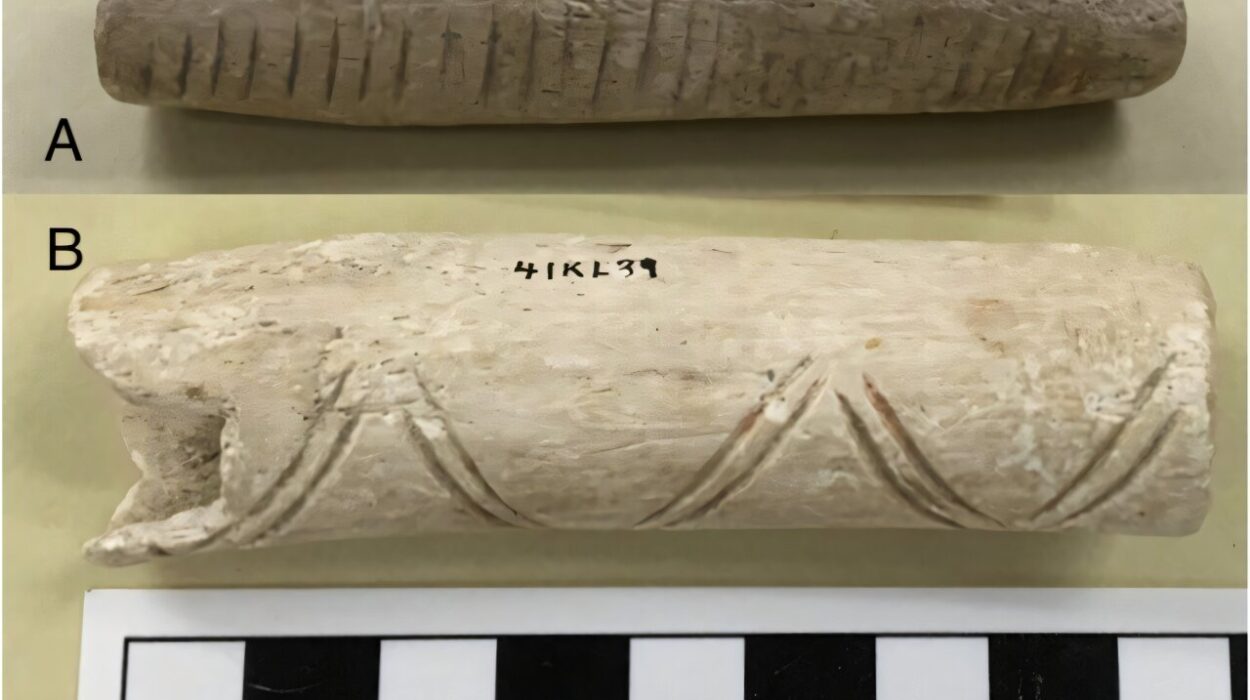

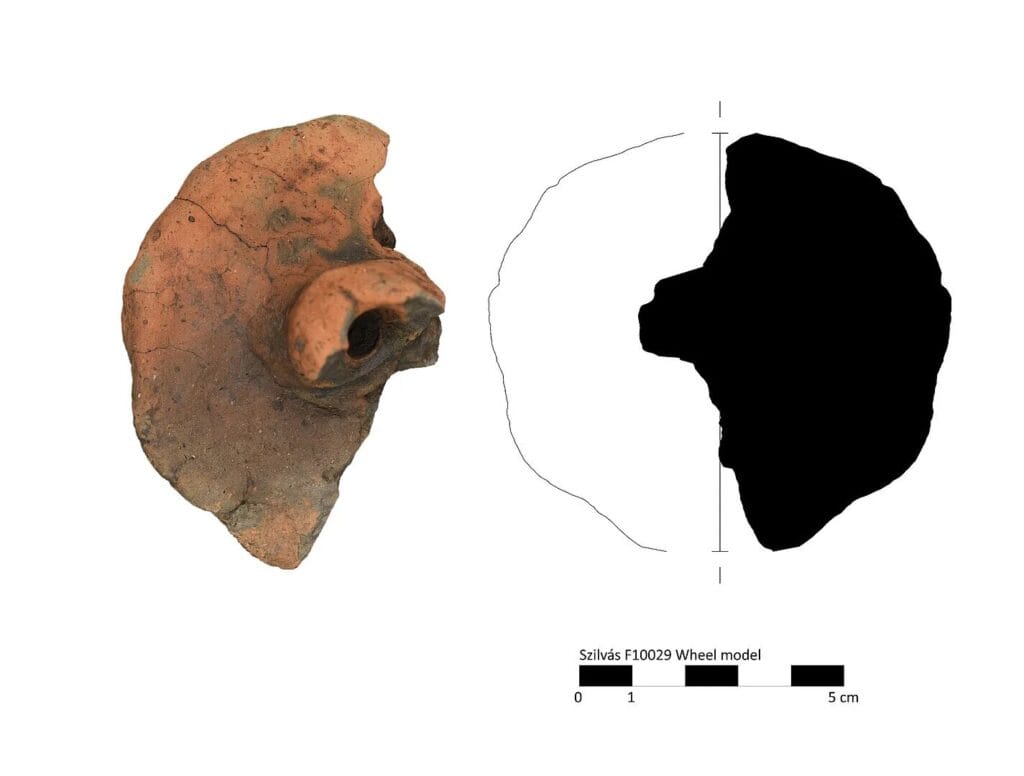

The settlement belongs predominantly to the Vinča culture, a civilization that flourished across the Balkans between 5400 and 4400 BCE. Known for its beautifully decorated ceramics and early signs of symbolic writing, the Vinča left behind a cultural fingerprint that has both intrigued and baffled archaeologists.

But this site doesn’t stand alone in Vinča purity. Alongside its signature motifs are strong influences from the lesser-known Banat culture. “This is also remarkable,” Wilkes notes, “as only a few settlements with material from the Banat culture are known from what is now Serbia.”

Here in the sediments of Jarkovac, two cultural currents seem to flow together—suggesting exchange, migration, perhaps even social blending. These overlapping traditions offer a tantalizing view into how ideas, technologies, and identities moved through prehistoric Europe.

In every sherd of ceramic and flake of obsidian, in every trench and ditch, the past whispers that the Neolithic was not a quiet age—it was dynamic, layered, and deeply human.

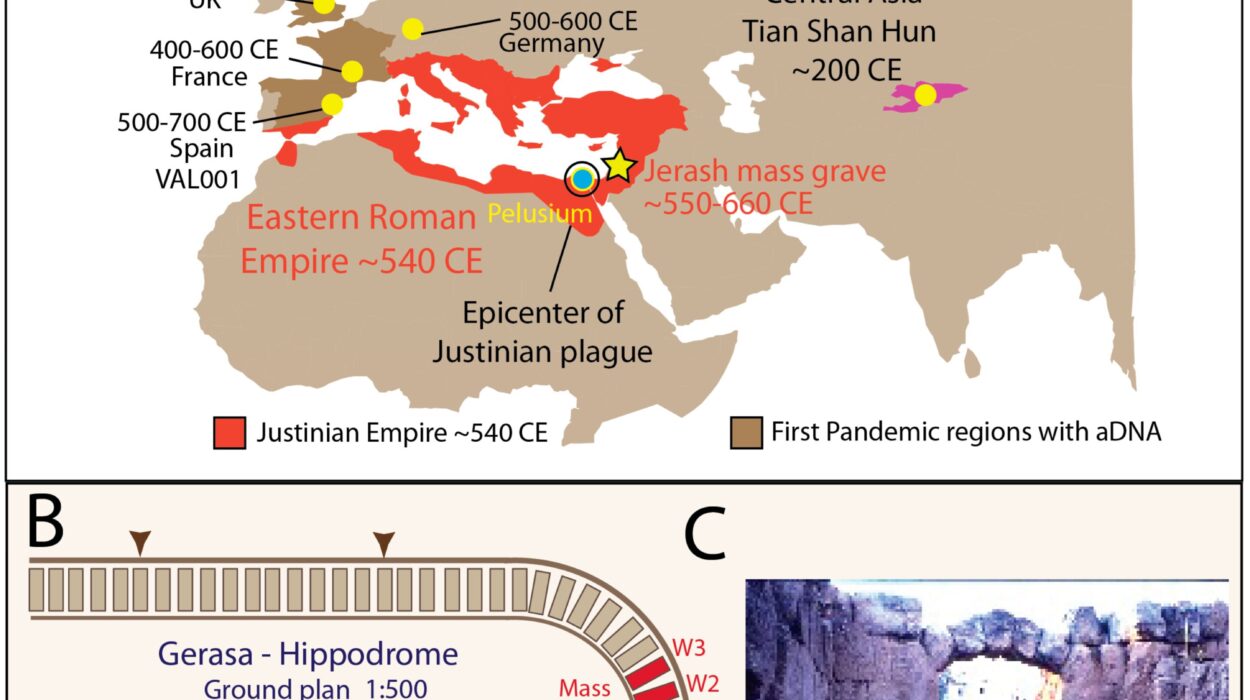

Hungary’s Circular Mysteries: Rewriting the Timeline

While the Serbian plains revealed a Neolithic metropolis, the team extended their gaze westward into Hungary. There, in collaboration with researchers from the Janus Pannonius Museum in Pécs, they set out to re-examine mysterious circular features known as “rondels.” Long assumed to be part of the Late Neolithic Lengyel culture (roughly 5000–4500 BCE), these giant circular ditches may have served as gathering places, observatories, or ritual centers. Their purpose remains debated, but their presence suggests highly organized, ceremonial societies.

Using the same geophysical tools that unveiled the Serbian site, the team peeled back the layers of time around these rondels—only to find something unexpected.

“In some cases,” says Kata Furholt, co-team leader and researcher at Kiel University, “sites previously categorized as Late Neolithic turned out to be much younger.” What had once been assigned to the era of early farmers now appears to belong to the Vučedol culture of the Late Copper Age and Early Bronze Age (roughly 3000–2400 BCE).

This revelation forces archaeologists to rethink what these rondels really were—and more importantly, when and why they were built. As the ground yields its secrets, the narrative of early European societies grows more complex and less linear. Cultures did not simply evolve along a clean timeline. They overlapped, competed, borrowed, and disappeared. The past, like the earth itself, is uneven.

Inequality Beneath the Fields

Beyond the impressive size of the Serbian settlement or the enigmatic rondels in Hungary, this research is part of a much larger and more human question: How did inequality begin?

The ROOTS Cluster of Excellence is investigating precisely that. Through their “Inequality of Wealth and Knowledge” project, they are tracing the earliest roots of how humans divided labor, hoarded resources, and transmitted knowledge unevenly.

“Southeast Europe is a very important region to answer how knowledge and technologies spread in early human history,” explains Professor Furholt. “This is where new technologies such as metalworking first appeared in Europe.”

Indeed, the seeds of what would later become stratified societies—monarchs and peasants, literate and illiterate, rich and poor—were already germinating in these early settlements. Access to tools, control over storage, mastery of farming techniques—these became sources of power long before the sword or crown.

The newly identified site in Jarkovac may offer a pristine laboratory to explore those beginnings. Its size alone implies coordinated labor. Its structured layout suggests roles and possibly leadership. And its combination of cultural influences hints at information flow—who knew what, and who got to use that knowledge.

A World Once Lived, Now Underfoot

It’s easy to forget, in the comfort of modern life, how much human experience lies beneath our feet. Every field, every roadside, every unremarkable plot of earth might contain echoes of voices, intentions, and ideas long buried. In the quiet hours of the Serbian plain, 7,000 years ago, children may have laughed, artisans molded clay, and elders looked to the horizon wondering what lay beyond.

Now, thanks to the persistent curiosity of science and the humility to listen to what the soil has to say, we are beginning to glimpse the patterns of their lives.

This is not just about ruins. It’s about us. It’s about where we came from—and how the decisions made by people with no writing, no metal, and no monuments still shaped the inequality and knowledge systems we live within today.

The story of the Neolithic isn’t finished. It’s being rewritten with every signal that pulses from the earth, every shard that’s dusted off, every hypothesis that collapses under new data. In the newly discovered city near Jarkovac, the past has spoken.

And we, finally, are listening.