When the Roman Empire swept into Britain in AD 43, it promised transformation. Roads, baths, cities, governance, commerce, culture. The Romans described their mission as bringing “civilization” to the people of Britannia. Yet somewhere beneath those grand promises, something quieter and far more human was happening. Bodies were changing. Health was shifting. And centuries later, bones buried in English soil still carry the imprint of that upheaval.

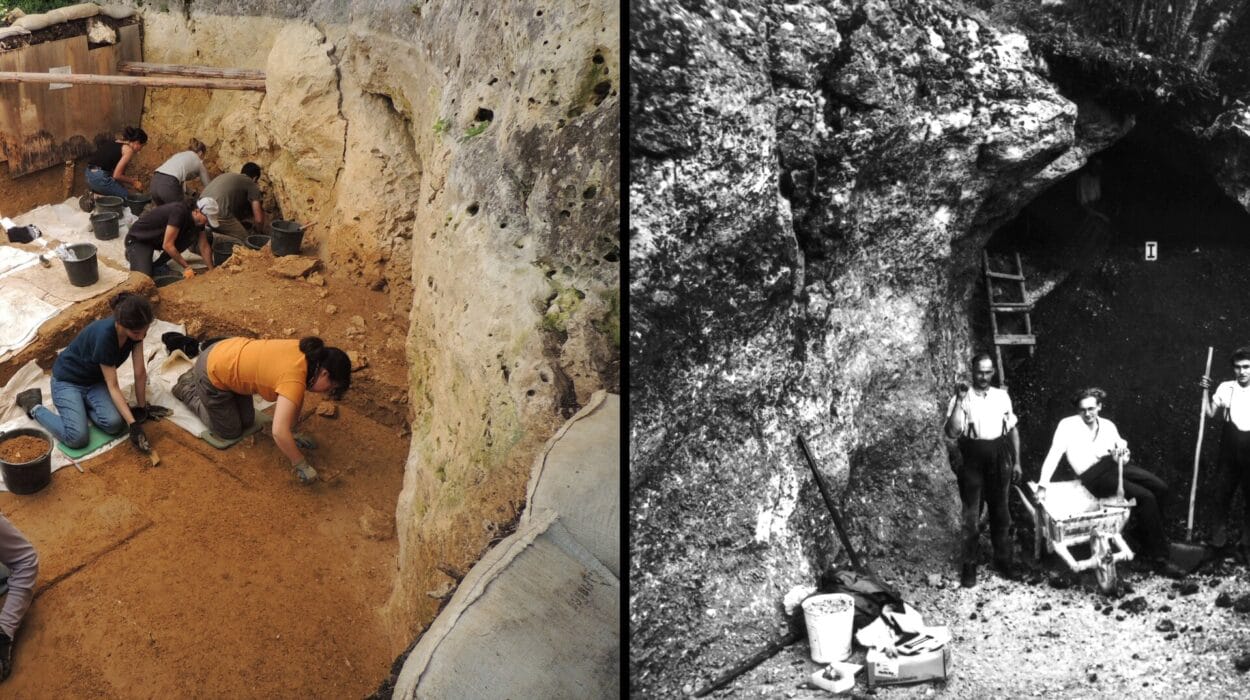

For decades, historians have believed that Roman urbanization damaged public health. But the question of how life compared before Rome’s arrival has been surprisingly difficult to answer. The Iron Age, with its fragmented funerary traditions, left behind few intact bodies to examine. And without those bones, the story of what changed under Roman rule remained incomplete.

A new study led by Rebecca Pitt of the University of Reading turns this mystery on its head. Not by finding more bones, but by listening differently to the ones that remain.

The Challenge of Reading a Broken Past

Iron Age death did not look like Roman death. And that difference is crucial.

“Iron Age funerary rites are very different to the organized cemeteries we often associate with the dead. Instead, their customs largely demonstrate that they believed fragmenting the body was required to release the soul into the afterlife,” Pitt explains. “This complicates analysis of this period as there are comparatively fewer human remains available for study, and examination of the complete skeleton cannot always take place.”

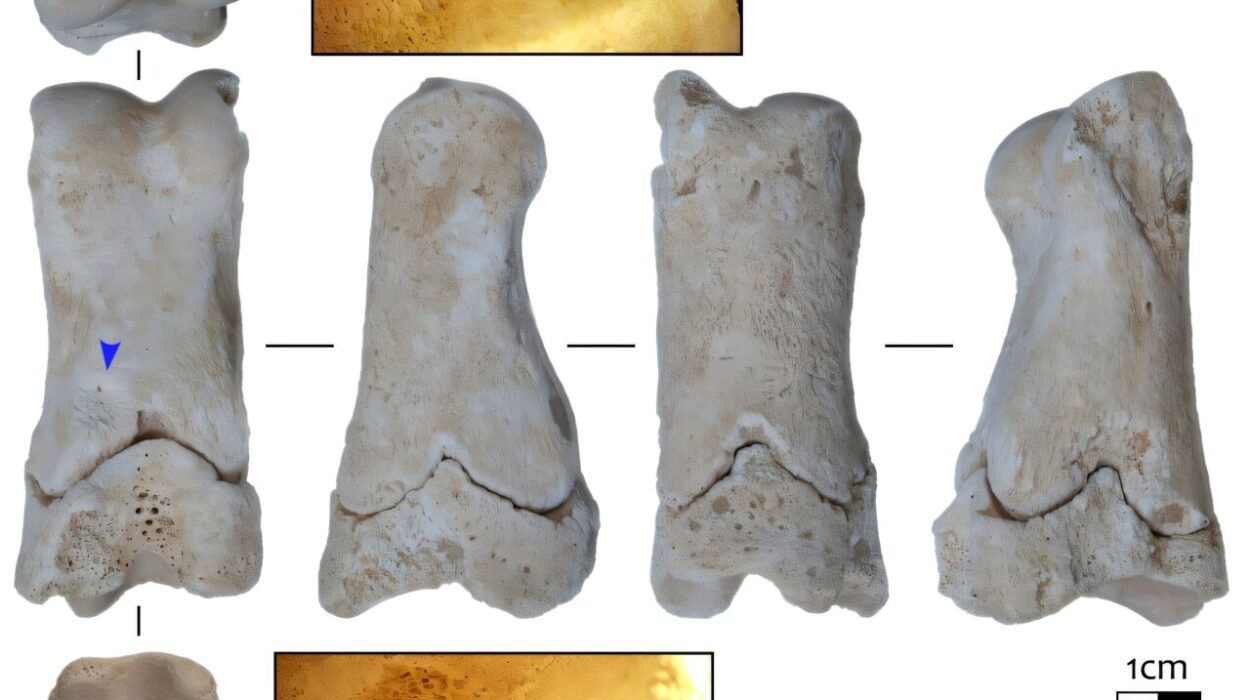

But there was one exception. While adults were often cremated or disassembled, infants were not. Babies below age two were frequently buried intact, offering a rare, unbroken window into Iron Age health. That detail became the cornerstone of Pitt’s investigation.

Instead of comparing adults alone, she turned to a concept known as the DOHaD hypothesis. It suggests that the early experiences of a child, especially under the age of two, reverberate across a lifetime.

“The DOHaD hypothesis suggests that what a child below the age of 2 years experiences will have an impact on their health and development throughout their lifetime,” Pitt explains. “This means that factors which we refer to as ‘stressors,’ essentially disease, malnutrition, or maybe even a traumatic event, can influence an individual’s epigenetic signatures, which in turn can result in health issues later in life and even impact subsequent generations.”

In the bones of infants and in the bones of mothers, Pitt saw a way to trace stress through time.

Tracing Mothers, Infants, and the Weight of a Changing World

“Mothers and infants are underrepresented in historical accounts,” Pitt notes. That absence matters. These two groups often endure the earliest and deepest consequences of environmental and social change. By placing infants and reproductive adults side by side, Pitt set out to map how urbanization reshaped health across generations.

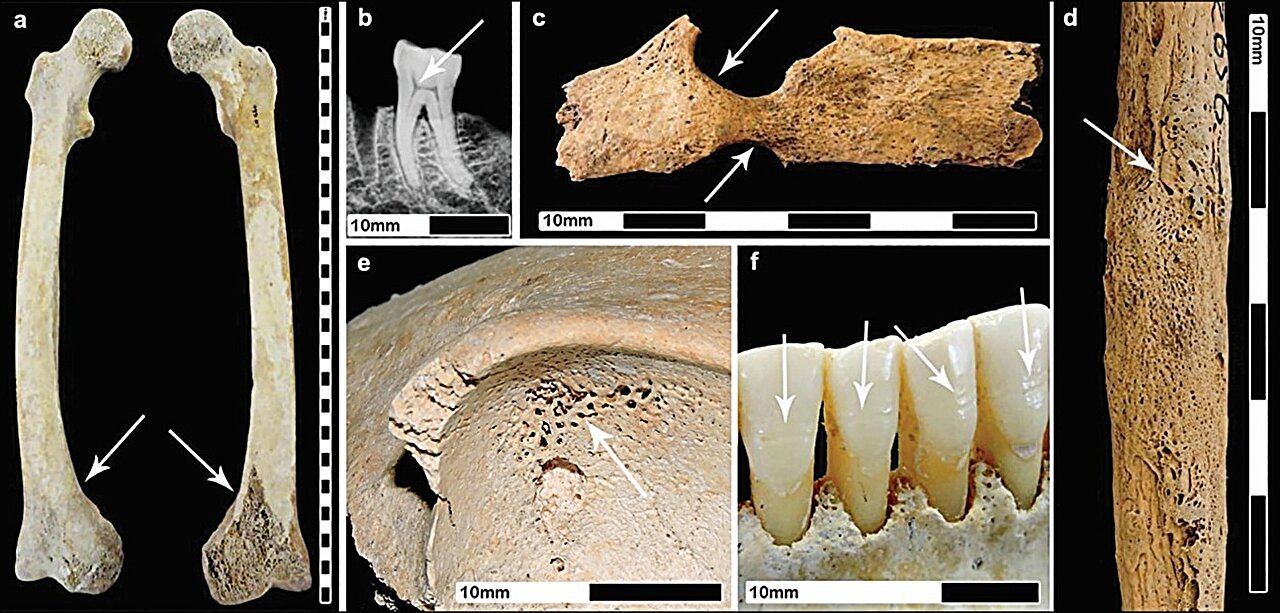

Her study examined 646 individuals, including 372 non-adults and 274 adult females, taken from Iron Age and Romano-British sites across south and central England. Some lived in emerging Roman cities. Others lived in rural settlements shaped by older traditions. Their bones carried clues not only about how they died, but how they had lived.

Pitt identified ages at death and examined health indicators such as skeletal lesions. She then compared these traits statistically across Iron Age populations, rural Roman communities, and urban Roman centers.

Through this comparison, a striking pattern emerged.

The Cities That Promised Civilization but Delivered Decline

Pitt’s results confirmed the long-held suspicion that health declined under Roman rule. But the story was more nuanced than expected.

She found that negative health markers rose sharply in the Roman Period, but only in urban centers such as civitas capitals. These were the places where Romanization was strongest. They were also places where density, class divides, and new infrastructure reshaped daily life.

Urban residents lived in crowded and polluted environments. They endured limited access to resources. They were exposed to lead, an integral part of Roman plumbing and construction. The result was a decline in health that was not just immediate but long-lasting.

By contrast, rural communities lived a different story. Though they showed slightly increased pathogen exposure, their overall health did not statistically differ from Iron Age populations. Their lives, in many ways, continued along older traditions. Their bones did not carry the same burden of stress seen in the cities.

And that quiet continuity raises questions about how deeply Roman authority penetrated into the countryside. Rural Britons may have preserved more of their Iron Age ways than previously believed.

Echoes Across Generations

The power of this research lies not only in what it reveals about the past, but in how it shows stress rippling across time. Urbanization didn’t simply affect one generation. According to Pitt’s interpretation through the DOHaD lens, it shaped the health of children, and potentially the children’s children.

The stressors of a polluted environment, limited access to food, exposure to disease, and the hardships of city life may have left marks at the epigenetic level. Bones alone cannot capture everything, but they can whisper of strain carried from mother to infant in the most formative years.

Pitt describes these long-term effects clearly. “By looking at mother-infant experiences together, we can observe the long-lasting impact urbanization has on the health of individuals, with negative health signatures passed from mothers to their children.”

In this way, the story of Roman Britain becomes not only a political or cultural narrative but a biological one.

Why This Research Matters Today

At the end of her study, Pitt draws a line straight from ancient bones to modern lives.

“I believe this has major connotations to the health of modern communities,” she concludes. “Currently, children are being born into an increasingly polluted world, and a growing number of families are struggling with the cost of living. This can severely impact the development of young children, and result in a major impact on their health and well-being, which will last throughout their lifetime and possibly into future generations.”

It is a sobering reminder. The ancient Romans did not intend to create harm when they built their cities. They pursued infrastructure, order, and expansion. Yet in doing so, they changed the environment in ways that reshaped the bodies of those who lived within it.

Today’s world is shaped by different forces but driven by the same challenge. Pollution is rising. Urban hardship grows. Economic pressures weigh heavily on families. And like the infants of Roman Britain, children today may carry the imprint of stress into their futures.

Pitt’s findings reveal more than a historical shift. They show that the body remembers. Communities remember. Generations remember.

And understanding this legacy may be one of the most important steps in navigating the health challenges we face now, just as surely as the people of Roman Britain faced theirs two thousand years ago.

More information: Rebecca Pitt, Assessing the impact of Roman occupation on England through the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) hypothesis, Antiquity (2025). doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2025.10263