Imagine Europe tens of thousands of years ago—a land cloaked in vast forests, where herds of elephants and bison thundered across open plains and giant deer grazed beneath towering oaks. Rivers flowed untamed, and glaciers loomed in the north, their icy breath shaping the winds that swept through valleys alive with life. In this wilderness, small bands of humans—first Neanderthals, then Mesolithic hunter-gatherers—moved through the landscape armed with nothing more than fire, spears, and an extraordinary will to survive.

For centuries, we imagined these early humans as passive inhabitants of a pristine wilderness, existing in harmony with an untouched natural world. But new research challenges this romantic vision. A recent study published in PLOS One reveals that even before the dawn of agriculture, humans were already powerful ecological forces—reshaping Europe’s forests, altering the balance between species, and leaving a lasting imprint on the continent’s ecosystems.

Rewriting the Story of Prehistoric Europe

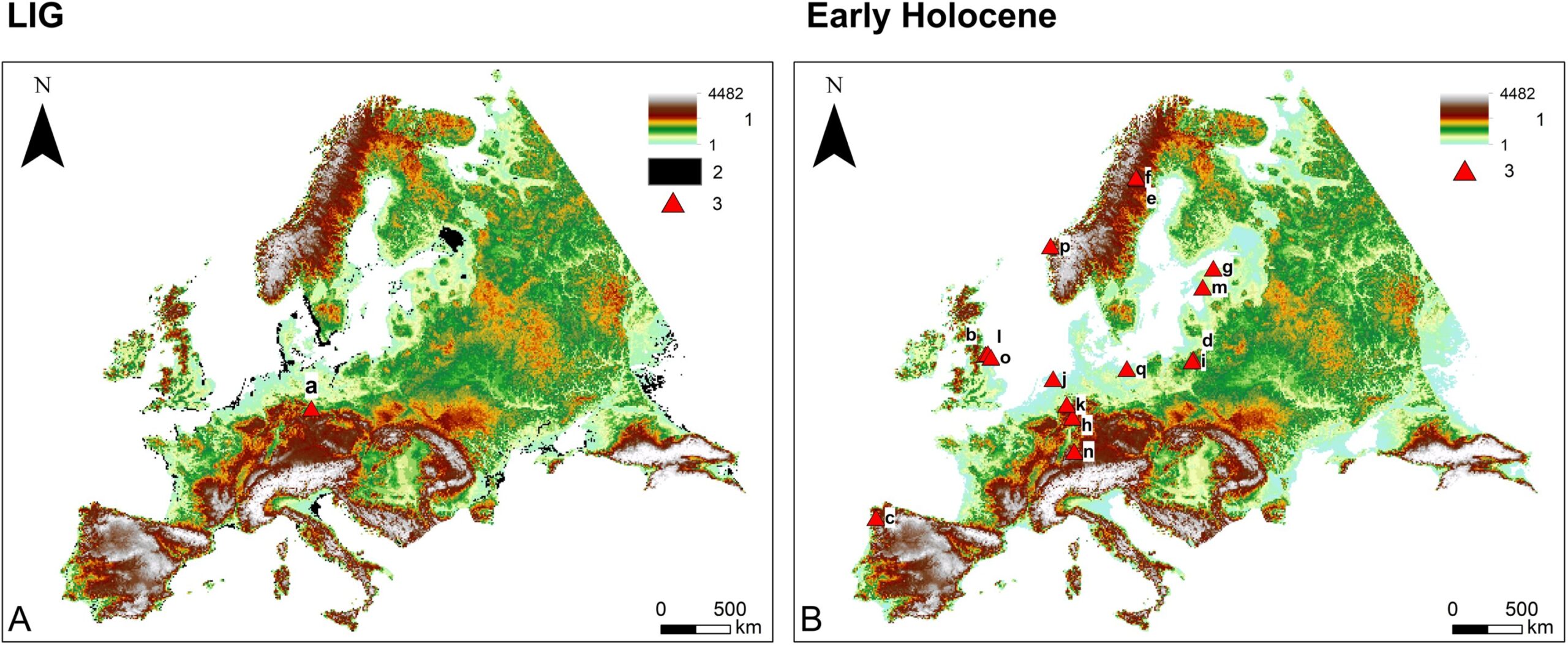

An international team of scientists led by researchers from Aarhus University in Denmark set out to explore how climate, wildlife, fire, and humans shaped Europe’s vegetation during two ancient warm periods. Using advanced computer simulations combined with extensive pollen data, they reconstructed how landscapes might have looked—and how they changed—over thousands of years.

Their conclusion was startling: neither climate shifts nor natural fires nor the presence of large herbivores alone could explain the changes seen in ancient vegetation. When human activity was added to the equation, however, the models suddenly fit. Humans—both Neanderthals and later Homo sapiens—had been influencing Europe’s landscapes far earlier and more profoundly than previously assumed.

“The study paints a new picture of the past,” said Jens-Christian Svenning, professor of biology at Aarhus University and one of the lead researchers. “It became clear to us that climate change, large herbivores, and natural fires alone could not explain the pollen data results. Factoring humans into the equation—and the effects of human-induced fires and hunting—resulted in a much better match.”

In other words, humans were not just another species in the ecosystem; they were already shaping it.

Neanderthals and the First Human Footprints on Nature

The team examined two key time periods: the Last Interglacial, roughly 125,000 to 116,000 years ago, and the Early Holocene, about 12,000 to 8,000 years ago. The first belonged to the Neanderthals—the robust, intelligent cousins of modern humans. The second belonged to our own ancestors, the Mesolithic hunter-gatherers, who spread across Europe after the last ice age.

During the Last Interglacial, Europe was a paradise for megafauna. Elephants, rhinoceroses, and massive bison roamed freely alongside aurochs, horses, and deer. It was a landscape dominated by life on a grand scale—giant animals maintaining open grasslands by grazing and trampling the soil, keeping forests in check.

Yet even in this lush and untamed era, Neanderthals were not mere bystanders. They hunted large game, including mammoths and elephants weighing up to 13 tons. Their fires, used for warmth, light, and hunting, occasionally burned through forests, opening clearings that would alter vegetation for generations.

Though the Neanderthals were few in number, their actions still left measurable effects. The new study estimates that Neanderthals influenced about 6% of plant type distribution and up to 14% of vegetation openness. It’s a small but significant footprint—a sign that even sparse populations of ancient humans could subtly shift the balance of ecosystems through fire and hunting.

“The Neanderthals did not hold back from hunting and killing even giant elephants,” Svenning explained. “Hunting also had a strong indirect effect. Fewer grazing animals meant more overgrowth and thus more closed vegetation. However, the effect was limited, because the Neanderthals were so few that they did not eliminate the large animals or their ecological role—unlike Homo sapiens in later times.”

Homo Sapiens: The Great Transformers

By the time Homo sapiens entered the European scene around 40,000 years ago, everything began to change. Humans multiplied, refined their tools, and developed new strategies for survival. By the Mesolithic period, roughly 12,000 years ago, they had become expert hunters, skilled in manipulating their surroundings.

According to the simulations, Mesolithic hunter-gatherers could have influenced as much as 47% of Europe’s vegetation distribution. This staggering figure reveals the scale of their impact. Through controlled burning, clearing undergrowth, and hunting large herbivores to near-extinction, these early humans were transforming the landscape long before they planted a single seed or built a permanent village.

The disappearance of large animals played a crucial role. When humans hunted down mammoths, aurochs, and wild horses, they disrupted the natural balance that kept forests open. With fewer grazing giants to maintain meadows and prairies, trees and shrubs began to reclaim the land, changing open grasslands into dense forests.

In essence, humans reshaped Europe by accident. Their fires and hunting altered the very fabric of ecosystems, demonstrating that even in the absence of agriculture, humanity had already become an ecological engineer.

The Myth of the Pristine Wilderness

This revelation forces us to reconsider one of the most enduring myths in human history—the idea that there once existed a “pure,” untouched nature.

For centuries, we have imagined prehistoric Europe as a pristine wilderness that only began to change when agriculture spread across the continent. But the new evidence tells a different story. Even without farming, hunter-gatherers were active co-creators of the environment. They didn’t passively live in nature; they interacted with it, shaped it, and adapted it to their needs.

“The Neanderthals and the Mesolithic hunter-gatherers were active co-creators of Europe’s ecosystems,” said Svenning. “The study is consistent with ethnographic studies of contemporary hunter-gatherers and archaeological finds, but goes a step further by documenting how extensive human influence may have been tens of thousands of years ago—that is, before humans started farming the land.”

The idea that early humans influenced ecosystems resonates with what we know from Indigenous cultures around the world. From Aboriginal Australians using fire to manage landscapes to Native American communities shaping forests and grasslands through selective burning, humans have long been part of nature’s rhythm—not separate from it.

How Science Reconstructed the Past

To uncover these deep-time dynamics, the research team used an extraordinary combination of disciplines: ecology, archaeology, palynology (the study of ancient pollen), and artificial intelligence.

Pollen grains preserved in sediment cores act like time capsules, revealing which plants grew in a region thousands of years ago. By comparing pollen data with simulated vegetation models, scientists can infer what factors—climate, wildlife, or human activity—were driving changes in plant cover.

“This is the first simulation to quantify how Neanderthals and Mesolithic hunter-gatherers may have shaped European landscapes,” explained lead author Anastasia Nikulina. “Our approach has two key strengths: it brings together an unusually large set of new spatial data spanning the whole continent over thousands of years, and it couples the simulation with an optimization algorithm from AI. That lets us run a large number of scenarios and identify the most possible outcomes.”

Through these simulations, they could finally see what earlier researchers had only suspected: humans were already altering landscapes on a continental scale long before the first farmers arrived.

Fire, Hunger, and the Making of a Continent

Fire was humanity’s first great tool—and its first great weapon against nature. Controlled burns helped hunter-gatherers clear forests, flush out game, and encourage the growth of certain plants. In doing so, they unknowingly engineered new ecosystems, replacing dense woodland with mosaics of grasslands and shrubs that supported different species.

At the same time, hunting large animals changed the structure of ecosystems. When elephants or bison disappeared from a region, the vegetation thickened. Grasslands turned to woodland, and sunlight vanished from the forest floor. These changes cascaded through food webs, affecting everything from insects to predators.

The ancient humans who walked those forests could never have imagined how their fires and hunts would echo across millennia. Yet, their actions marked the dawn of a new force in nature—a force that would eventually come to dominate every corner of the Earth: us.

The Legacy of Early Human Influence

What makes this study so compelling is not just its insights into the distant past, but what it says about our present and future. The story of early human influence reminds us that humans have never been separate from the natural world. We have always been participants, shapers, and sometimes destroyers of ecosystems.

Even before cities and farms, our ancestors had begun writing their signature on the planet. The forests that regrew after the ice ages, the animals that survived the megafaunal extinctions, and the landscapes that stretched across ancient Europe were all products of human interaction with nature.

Today, as we face the environmental crises of our own making—deforestation, climate change, and biodiversity loss—understanding this deep history becomes more important than ever. It shows that human impact is not a modern phenomenon; it is part of what makes us human. The difference now is scale.

Looking Beyond Europe

The researchers hope to extend their methods to other regions of the world. North and South America, as well as Australia, present unique opportunities for comparison. These continents were never home to earlier hominins before the arrival of Homo sapiens, meaning researchers can contrast what ecosystems looked like with and without human influence.

“And although the large models paint a broad picture, detailed local studies are absolutely essential to improve our understanding of the way humans shaped the landscape in prehistoric times,” said Svenning.

By combining large-scale simulations with archaeological evidence, scientists can continue to uncover the hidden stories of how humanity reshaped the planet—one fire, one hunt, and one footprint at a time.

The First Ecologists

There is a certain poetry in realizing that the world we know today—the forests, the meadows, the mosaic of landscapes that define Europe—was partly the work of our distant ancestors. They were not conservationists in the modern sense, but they understood the rhythms of the world. They lived in balance with it, even as they changed it.

In their fires flickering against the night sky, we can glimpse the first sparks of human agency—the moment when our species began to act not just within nature, but upon it.

Tens of thousands of years later, that same agency defines our planet. We are no longer small groups of hunter-gatherers altering patches of forest; we are billions of people reshaping entire ecosystems. But the story remains the same: wherever humans go, the Earth changes with us.

More information: Anastasia Nikulina et al, On the ecological impact of prehistoric hunter-gatherers in Europe: Early Holocene (Mesolithic) and Last Interglacial (Neanderthal) foragers compared, PLOS One (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0328218