For more than a century, the question of who first set foot in the Americas — and how they arrived — has hovered like an unresolved preface to human history. Now, a new analysis of ancient stone weapons has pushed that preface backward in time and outward across the Pacific. In doing so, it has placed the First Americans squarely inside the great Paleolithic conversation of the Old World, not at its margins.

Published in Science Advances, the study argues that ancient people did not wait for the great ice sheets to melt before crossing into the continent, nor did they march inland across a dry Arctic land bridge in a single late burst around 13,000 years ago. Instead, they came earlier — perhaps closer to 20,000 years ago — tracing a thin coastal corridor along the Pacific Rim, moving from Northeast Asia into the Americas as skilled hunters armed with an already ancient technology.

“This marks a paradigm shift,” said Loren Davis of Oregon State University, one of the study’s lead authors. “For the first time, we can say the First Americans belonged to a broader Paleolithic world — one that connects North America to Northeast Asia.”

Not Isolated Pioneers, but Linked Participants

For decades, archaeological debate turned on a geographic hinge: Did the first migrants cross by land over Beringia after the ice retreated, or did they skirt the Pacific in boats and small camps much earlier? The new comparison of stone tools tips the scale toward the sea.

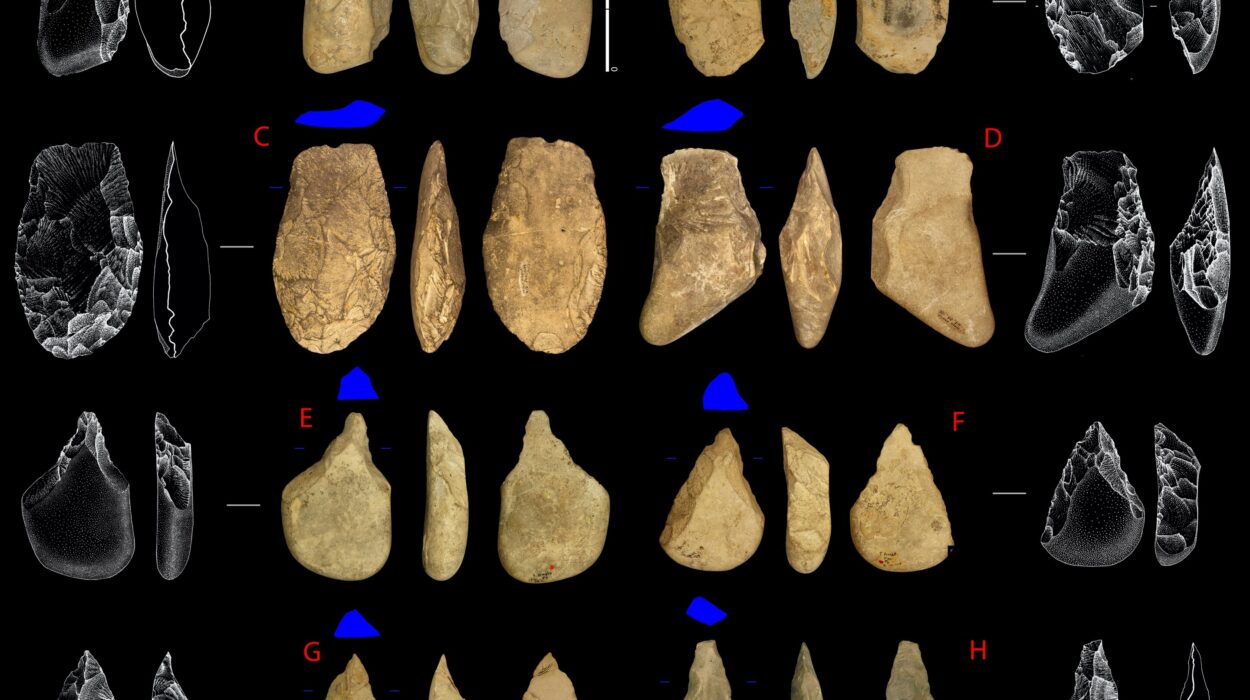

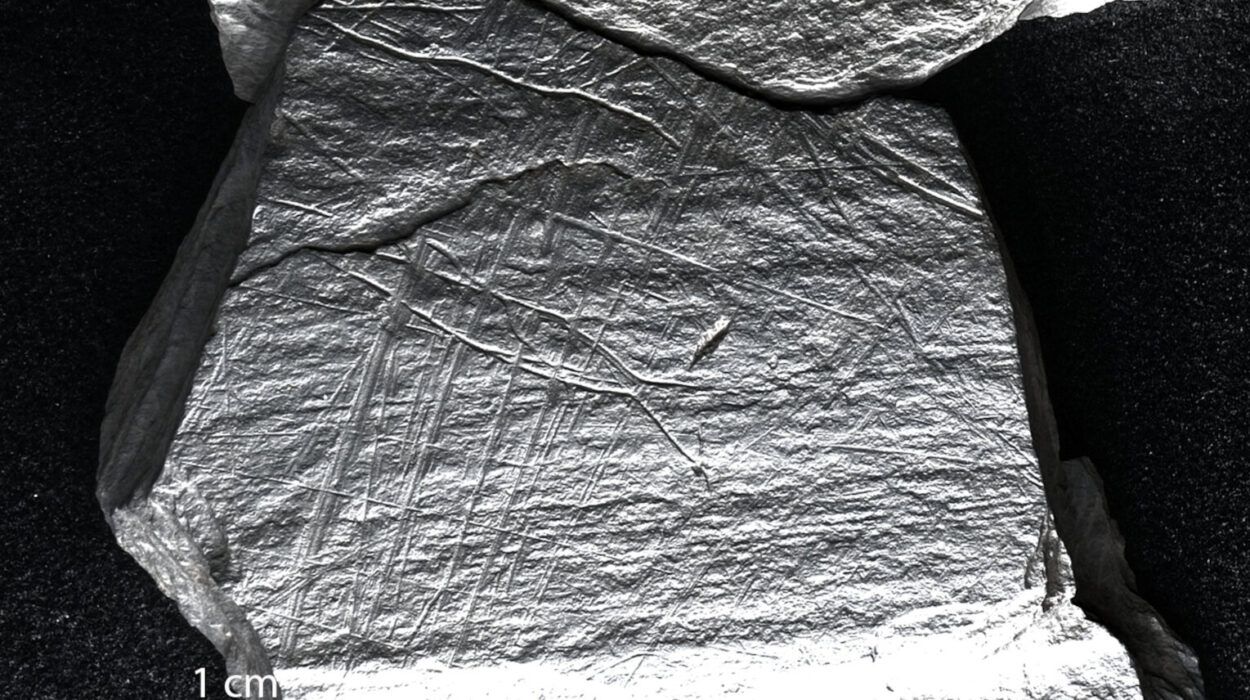

What Davis and his colleagues found was not only coincidence in shape or function, but a sequence — a technological lineage. The same class of double-flaked projectile points, known as bifaces, that appear in early American sites between 20,000 and 13,500 years ago already existed in Hokkaido, Japan’s northernmost island, at the earlier end of that window. The points are not crude improvisations but engineered weapons: thin, sharp, durable spear tips designed for puncturing game in cold lands where hunting meant survival.

To find such a system appear fully formed on American soil implies that it was carried, not reinvented. It implies memory. It implies connection.

“This study puts the First Americans back into the global story of the Paleolithic,” Davis said. “Not as outliers — but as participants in a shared technological legacy.”

A Pacific Highway of Ice and Sea

The coastal route theory envisions bands of hunter-seafarers advancing slowly down the Pacific Rim, moving along shorelines now drowned by post-ice-age seas, pausing on kelp-rich coasts, eating shellfish, marine mammals, and migrating birds. They would not have needed to wait for continental ice to retreat inland because the edge of the world — the place where glacier meets ocean — was already open. That corridor existed even at the height of glaciation.

The new stone-tool evidence gives this vision teeth. If early Americans had come only across the central Beringian interior, their earliest traces should cluster in Alaska and the Yukon. Instead, the strongest sites with the characteristic points appear far to the south and east — in Texas, Idaho, Pennsylvania and Virginia. Even fragmentary sites in Oregon, Wisconsin, and Florida echo the same pattern.

The path, in other words, does not point from the Arctic inward, but from the Pacific downward.

More Than Migration — Inheritance

The technological system Davis’ team tracked was not a single artifact style but a whole method: a dual architecture of core-and-blade production paired with biface manufacture. Together they formed the cognitive and technical scaffold from which later American hunting traditions evolved. It is a fingerprint — one that matches not only regions of North America but late Paleolithic Asia.

Genetic studies have already linked Indigenous peoples of the Americas to East Asian and Northern Eurasian roots. The stones now supply the behavioral bridge between those genomes: not only who people were, but what they knew and carried.

“We can now explain not only that the First Americans came from Northeast Asia, but also how they traveled, what they carried, and what ideas they brought with them,” Davis said. “It is a powerful reminder that migration, innovation, and cultural sharing have always been part of what it means to be human.”

A Hidden Record Beneath the Waves

Much of the clearest supporting evidence for this coastal migration may lie out of reach — on sea floors. When the ice sheets melted and global seas rose, the once-walkable shoreline of the Pacific Rim disappeared under water. Camps, middens, boat landings, butcher sites — all the historical fingerprints of the journey — may now sit dozens of meters below the tides. That loss does not diminish the logic of the route; it explains why the interior record, not the coastal, is what remains for archaeologists to examine.

In that sense, the new study is not a final word but a lighthouse. It does not close a debate but reframes where we should expect the next pages of evidence to lie — offshore, global, and linked.

Returning the Americas to the Human Map

For a long time, the settlement of the Americas was treated like an afterthought, a late and isolated detour on the long road of human evolution that unfolded elsewhere. The new analysis does the opposite: it draws a visible line between east and east — from the ice-rimed archipelagos of the North Pacific to the first campfires of the American continent.

It tells us that the people who crossed were not blank slates on uncharted land, but inheritors of a toolkit and a tradition already shared across half the world. The first chapter of American human history is not a lonely prologue carved in snow — it is another verse in the global Paleolithic narrative, written not in ink but in stone.

The stones, once silent, have begun to speak again. What they say is simple and transformative: the First Americans did not stand apart from humanity’s great dispersal. They belonged to it.

More information: David B. Madsen et al, Characterizing the American Upper Paleolithic, Science Advances (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.ady9545