In the quiet storage rooms of the Popol Vuh Museum at Francisco Marroquín University in Guatemala, three small teeth sat unnoticed for years. To most, they would seem like ordinary fragments of a past life, unremarkable relics in a vast skeletal collection. But when researchers examined them more closely, they uncovered a startling secret: these teeth, belonging to Maya children, bore jade inlays—a practice almost exclusively documented among adults of the Pre-Hispanic Maya world.

The finding, recently published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, is as surprising as it is rare. Until now, dental inlays in the Maya world were seen as a hallmark of adulthood, a practice linked to status, beauty, and perhaps even spirituality. Yet here, in the fragile remains of children only eight to ten years old, the same modifications were found.

The discovery forces us to rethink what we know about Maya childhood, social roles, and the deep symbolism of body modification. It also reminds us that even the smallest pieces of evidence—just three loose teeth—can open windows into entire worlds of cultural meaning.

The Maya Tradition of Modified Smiles

For the Pre-Hispanic Maya, the human body was more than flesh and bone. It was a canvas for identity, a reflection of belonging, beauty, and even cosmic connection. Archaeologists have long documented a wide variety of dental modifications among Maya adults, particularly between AD 250 and AD 1550, spanning the Classic and Postclassic periods.

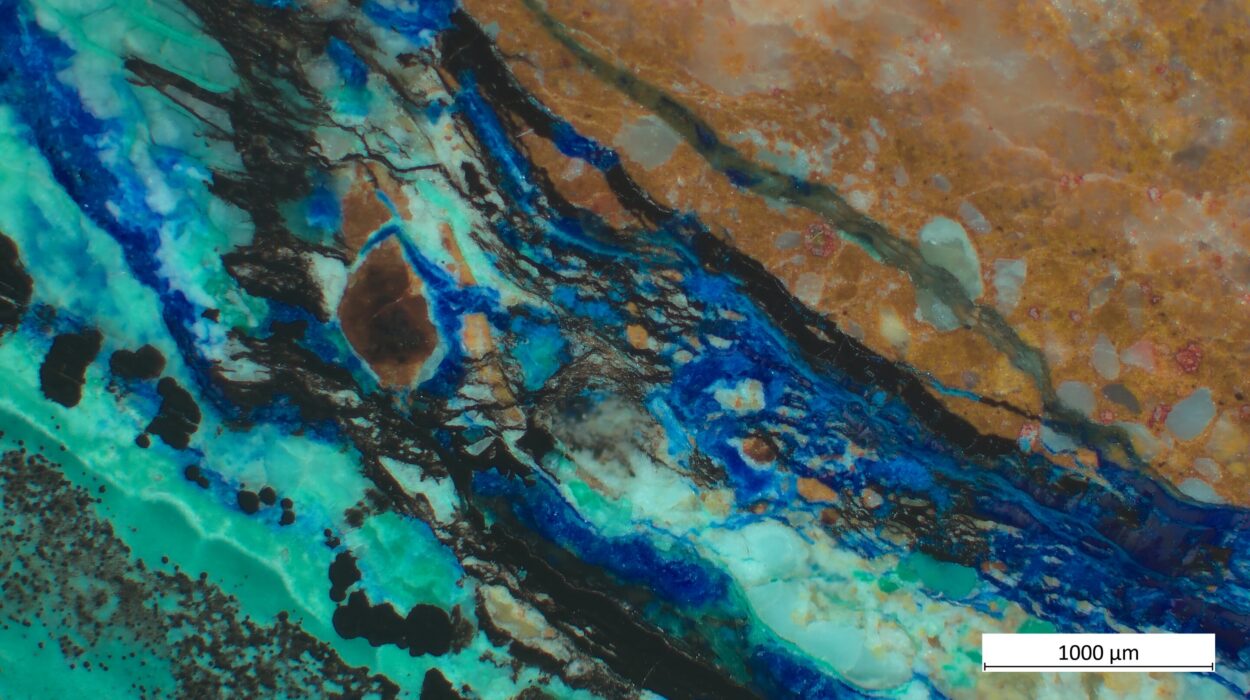

These modifications included filing teeth into distinctive shapes, engraving designs, and—most strikingly—embedding inlays of precious materials such as jade, turquoise, or obsidian. The process was delicate and deliberate: a lithic tool would carve out a small cavity in the enamel, into which a carefully shaped stone was inserted. An organic cement sealed the inlay in place, creating a permanent adornment that literally fused stone and body.

Such modifications were more than decorative. Jade, especially, held sacred meaning. To the Maya, jade symbolized life, fertility, and breath. To wear jade in one’s teeth was not merely to beautify the body but to embody sacred vitality itself.

But until now, these practices were almost exclusively associated with adults. Adolescents rarely showed signs of inlays before the age of 15, and children were never thought to have undergone such procedures in life. The three teeth from the Popol Vuh Museum upend this assumption.

The Children Behind the Teeth

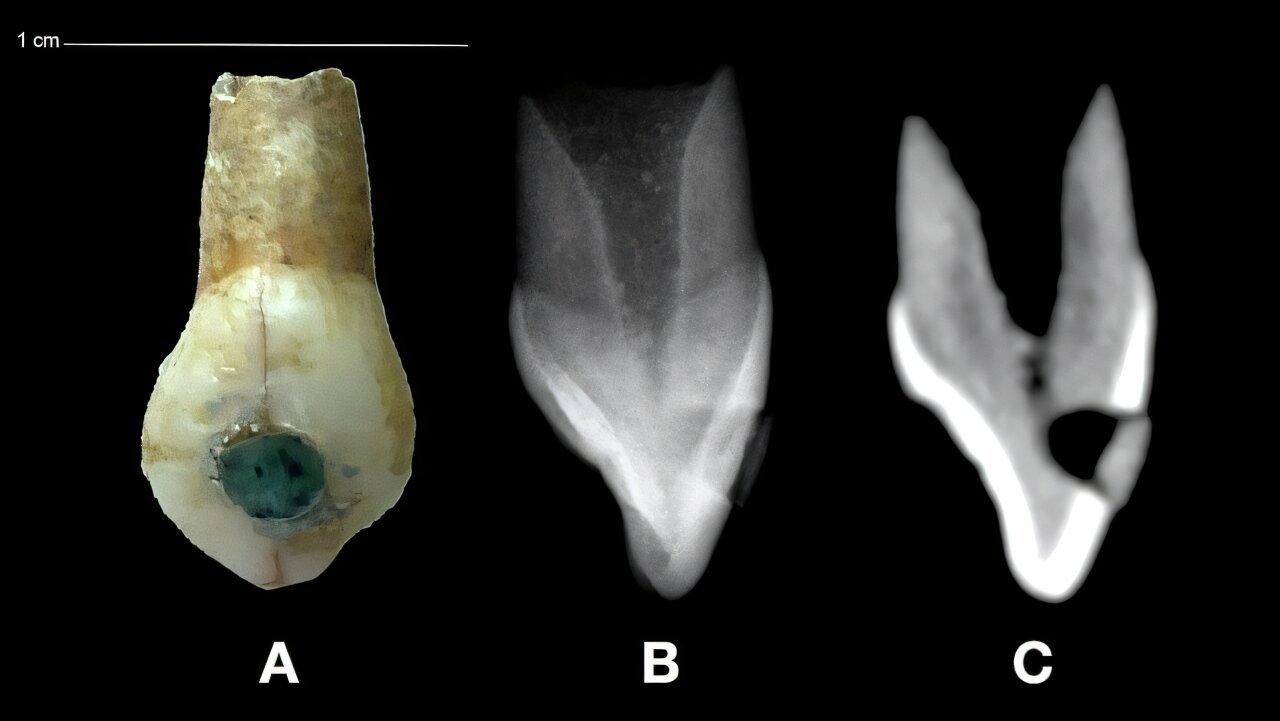

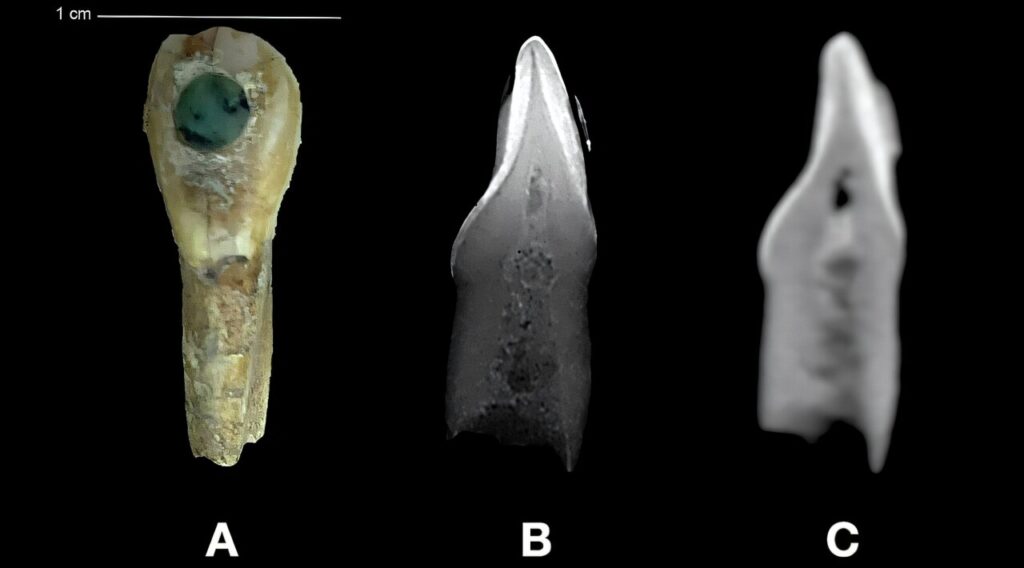

The study, led by Dr. Marco Ramírez-Salomón and colleagues, examined three teeth: a maxillary central left incisor, a mandibular lateral left incisor, and a maxillary right canine. Through microscopic and morphological analysis, the team determined that the teeth once belonged to children between eight and ten years old.

The incisors likely belonged to children around eight or nine years of age, while the canine came from a slightly older child, perhaps nine to ten years old. Importantly, the inlays were not postmortem additions or symbolic modifications after death. The researchers confirmed that the inlays were created during life, while the teeth were still functional parts of the children’s smiles.

This revelation makes the teeth the only known examples of living Maya children with jade dental inlays. Only one other case exists of a modified child’s tooth, a three- to four-year-old from Pusilha in Belize—but that individual received inlays after death, making the Popol Vuh examples unique in their vitality.

The Puzzle of Context

And yet, the teeth present as many questions as answers. “Unfortunately, these teeth… are loose teeth that were donated to the Museum,” explained study co-author Dr. Andrea Cucina. “Archaeologically speaking, they are completely decontextualized.”

That means the researchers do not know where the teeth were excavated, who the children were, or what circumstances surrounded their lives and deaths. There are no associated burial goods, no skeletal remains to provide further biological clues, no geographic markers to narrow down cultural variation.

Without context, the teeth are orphaned pieces of evidence—powerful, yet frustratingly incomplete. Still, careful analysis allows for informed speculation.

Why Children?

Why would Maya children receive a practice typically reserved for adults? Several hypotheses emerge.

One possibility is that the practice was regional rather than universal. Dr. Cucina suggests that the rarity of child inlays across the broader Maya archaeological record may indicate a localized tradition. Perhaps in one community, younger individuals were initiated into cultural practices earlier than elsewhere.

Another hypothesis is that dental inlays served as a marker of social maturity. Around the ages of eight to ten, Maya children often began to take on adult-like responsibilities. Girls would assist with housework, while boys might begin working in the milpas (maize fields). Dental inlays could have functioned as physical symbols of this transition—rites of passage literally etched into their bodies.

There is also the possibility of status and lineage. Jade inlays may have been reserved for elite families, signifying not only beauty but also social standing. If these children were members of elite households, their modified teeth could have reflected inherited prestige, an outward marker of belonging to a powerful lineage.

Whatever the case, the teeth suggest that Maya childhood may have been more fluid and complex than previously assumed. The boundary between child and adult, at least in some communities, could be marked not just by work and ritual but by permanent transformation of the body.

A Glimpse into Craft and Skill

Beyond the cultural implications, the teeth also reveal details about the artisans who performed the procedures. The two incisors show notable differences in craftsmanship.

The mandibular lateral incisor was inlaid with impressive precision. The cavity cut into the enamel was shallow, carefully avoiding the dentin beneath. In contrast, the maxillary central incisor shows a deeper and less cautious incision, cutting into the dentin layer but still sparing the pulp chamber.

These differences may reflect variation in the skill levels of the craftsmen. Alternatively, they may indicate that the teeth belonged to two different children, each attended by a different artisan. This possibility expands the narrative further, suggesting not only cultural significance but also a network of practitioners who specialized in the art of body modification.

The Emotional Weight of Tiny Remains

There is something deeply moving about these teeth. On the surface, they are scientific artifacts, data points in the study of ancient cultural practices. But on a human level, they are fragments of real children—children who lived, laughed, worked, and perhaps endured the pain of having jade stones set into their developing teeth.

It is easy to get lost in the technical details of archaeology: enamel layers, dentin penetration, organic cements. Yet beneath the science lies an intimate story. These were children whose lives intersected with traditions meant to beautify, sanctify, or empower the body. Their smiles once gleamed with the green of jade, connecting them to the sacred landscapes and cosmologies of their people.

And now, centuries later, their tiny teeth are all that remain to speak for them.

Beyond Beauty: What These Teeth Teach Us

Though decontextualized, these rare childhood inlays enrich our understanding of Maya culture in several key ways. They challenge the assumption that dental modification was an exclusively adult practice. They highlight the possibility of localized traditions within the broader Maya world. They raise questions about social maturity, status, and identity in childhood.

Most importantly, they remind us of the Maya’s extraordinary relationship with the body. To the Maya, teeth were not simply tools for eating—they were visible markers of personhood, capable of transformation through art and symbolism.

The three teeth from the Popol Vuh Museum may be small, but their significance is vast. They embody the fusion of biology and culture, of child and cosmos, of life and death.

Conclusion: Echoes from Small Voices

In the end, these three jade-inlaid teeth are more than archaeological curiosities. They are whispers from children who lived centuries ago, voices carried across time by enamel and stone. They remind us that even the youngest among the Maya could carry the weight of tradition, the marks of status, and the beauty of sacred materials in their very bodies.

While we may never know their names, their families, or the precise reasons behind their adorned smiles, we know this: their lives mattered. Their teeth, now studied with microscopes and published in journals, continue to tell stories—stories of identity, transformation, and the enduring human desire to leave a mark on the world.

And perhaps, as we gaze at these jade-filled fragments, we are invited to reflect on our own practices of self-expression and belonging, and the many ways in which even the smallest traces of our bodies can echo across centuries.

More information: Marco Ramírez-Salomón et al, Prehispanic Maya dental inlays in teeth with open apices: Implications for age of cultural practices, Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2025.105353