Long before the mighty cities of the Maya rose in the jungles of Central America, and centuries before the Aztecs built their grand empire in the Valley of Mexico, there existed a civilization shrouded in both mystery and marvel. They were the Olmecs—the first great civilization of the Americas. Emerging in the tropical lowlands of present-day southern Mexico, particularly in the states of Veracruz and Tabasco, the Olmecs flourished between roughly 1500 BCE and 400 BCE.

The Olmecs were not a minor society tucked away in obscurity; they were innovators, visionaries, and cultural architects. They created colossal works of art, established religious traditions that echoed through later civilizations, and laid the very foundation of Mesoamerican culture. Their legacy resonates even today, woven into the DNA of later societies, and preserved in the giant stone heads that gaze silently across the centuries.

But who were the Olmecs, and how did they manage to rise to such prominence in the ancient world? The answer lies not only in their achievements but in the story of how they transformed a challenging environment into the cradle of civilization.

The Heartland of the Olmecs

The Olmec civilization was born in the fertile but difficult terrain of Mexico’s Gulf Coast. This region is dominated by swamps, rivers, tropical forests, and humid climate. At first glance, it might not appear to be the ideal place for the rise of civilization. Yet the Olmecs turned this landscape into their advantage.

The rivers—including the Coatzacoalcos, Papaloapan, and Tonalá—were lifelines, providing fertile soil for agriculture, water for drinking and irrigation, and routes for transportation and trade. The lush environment teemed with resources: fish, game, clay, and stone. From this abundance, the Olmecs built not just villages but thriving centers of power.

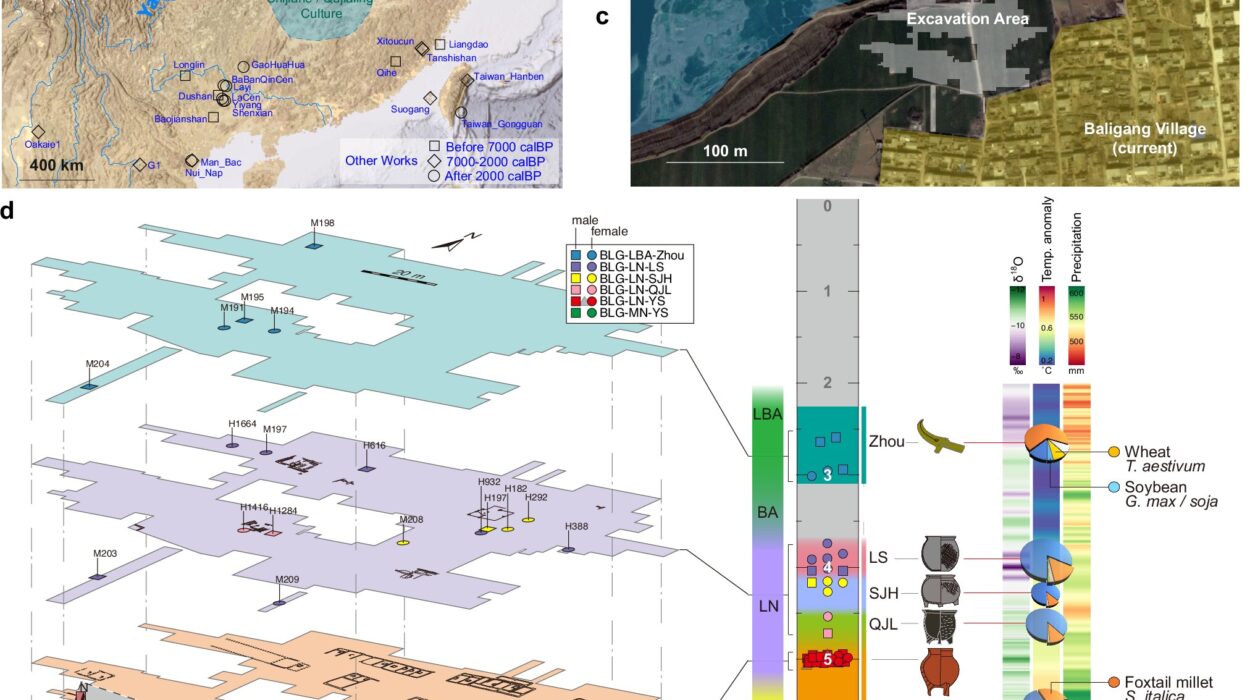

Archaeologists often refer to the Olmec “heartland,” which stretches across Veracruz and Tabasco. Within this zone lay the great ceremonial centers of San Lorenzo, La Venta, Laguna de los Cerros, and Tres Zapotes. These were not cities in the modern sense but monumental hubs of politics, religion, and trade—places where people gathered for rituals, where rulers commanded authority, and where artisans created works that still inspire awe today.

Agriculture and the Rise of Complexity

The foundation of the Olmec civilization rested on their mastery of agriculture. They cultivated maize, beans, squash, and cacao, staples that nourished their people and allowed populations to grow. With reliable food surpluses, the Olmecs could support artisans, priests, and rulers, as well as undertake massive construction projects.

Yet agriculture in the Gulf Coast was not without its challenges. The humid lowlands were prone to flooding, and maintaining stable fields required ingenuity. The Olmecs developed methods to manage water and to exploit the fertile alluvial soils. Their relationship with their environment was not simply one of survival but of transformation—reshaping the land to support civilization.

It is no coincidence that maize, a crop central to Olmec agriculture, became sacred throughout Mesoamerican history. For the Olmecs, as for the Maya and Aztecs who followed, maize was more than food; it was life itself, bound up with myths of creation and sustenance.

The Mystery of Olmec Society

Despite their achievements, the Olmecs left behind no written records that we can fully decipher. What we know about their society comes from archaeology, artifacts, and the echoes of their influence on later cultures. This has led to debates and speculation, but some aspects of their social and political structures can be discerned.

The Olmecs were almost certainly ruled by a powerful elite, perhaps divine kings who combined political authority with religious leadership. The monumental architecture of their centers, the scale of their sculptures, and the distribution of prestige goods all point to a society organized around hierarchy and central authority.

Priests and shamans likely held immense influence, mediating between the human world and the realm of gods and spirits. The Olmecs developed a cosmology that revolved around sacred mountains, fertility, and powerful deities. Jaguars, serpents, and supernatural hybrids appear repeatedly in their art, symbols of transformation, power, and the connection between the natural and spiritual worlds.

Beneath the elite, farmers, artisans, and laborers formed the backbone of Olmec society. Their collective efforts sustained the great centers, crafted the stunning artifacts, and carved the massive monuments that define the civilization.

Colossal Heads: Faces of Power

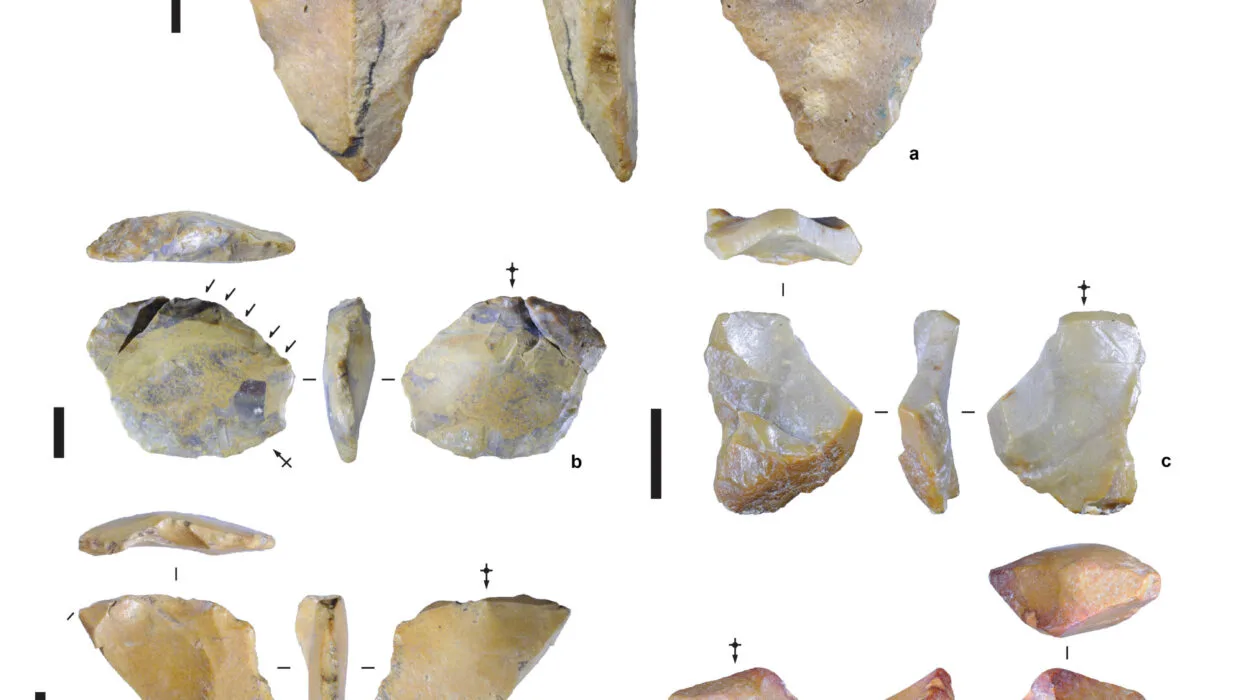

Perhaps the most iconic legacy of the Olmecs is their colossal stone heads. Ranging in height from about 5 to over 11 feet and weighing up to 40 tons, these monumental sculptures are extraordinary not only for their size but for their realism. Each head is distinct, with unique facial features, headdresses, and expressions, suggesting that they represent individual rulers rather than generic deities.

The sheer effort involved in creating these heads is staggering. The basalt used to carve them came from quarries located miles away, often in the Tuxtla Mountains. Transporting such massive stones without wheels or beasts of burden required immense labor and ingenuity, likely involving rafts, rollers, and coordinated human effort.

These heads are more than works of art—they are statements of power. Their presence in ceremonial centers reinforced the authority of rulers, immortalizing their image in stone. They also reveal the Olmecs’ advanced skills in sculpture, engineering, and organization.

Even today, standing before an Olmec colossal head inspires awe. They are silent, stoic reminders of a people who could command both nature and human labor to project their vision of leadership.

Art and Symbolism

Olmec art is as enigmatic as it is beautiful. From intricately carved jade figurines to massive stone monuments, their works reflect deep symbolism and complex spiritual beliefs.

One of the most common motifs is the “were-jaguar”—a human-jaguar hybrid figure with downturned mouth and almond-shaped eyes. Scholars debate its meaning: was it a deity, a symbol of shamanic transformation, or an emblem of power? Whatever its interpretation, it reveals the central role of animals, particularly the jaguar, in Olmec cosmology.

The Olmecs were masters of jade, a precious green stone that symbolized fertility, life, and the sacred. Small jade figurines, masks, and ornaments have been found in burial sites and ritual caches, demonstrating the stone’s role in religious and political life.

Their art was not merely decorative but symbolic, serving as a language of belief, identity, and authority. Through these artifacts, we glimpse a society where spirituality permeated every aspect of existence.

Religion and the Sacred World

The Olmec worldview was shaped by the interplay of natural forces, fertility, and the divine. Mountains, rivers, caves, and animals held sacred significance, and rituals sought to maintain balance between human beings and the spiritual cosmos.

Olmec deities were not simple gods but complex beings often represented in hybrid forms—part human, part animal. Among the most prominent were the jaguar god, associated with fertility and rain; the serpent, linked to water and renewal; and the bird, symbolizing the sky and heavens.

Ritual practices likely included offerings, bloodletting, and perhaps even human sacrifice, although evidence remains debated. Ceremonial centers, with their plazas, altars, and pyramids, functioned as sacred landscapes where the human and divine worlds converged.

The Olmecs also pioneered rituals that would echo through Mesoamerican history, such as the sacred ballgame. Although the exact rules remain unclear, the game had profound religious and political significance, symbolizing cosmic battles and cycles of life and death.

Centers of Power: San Lorenzo and La Venta

Two sites stand out as the greatest achievements of the Olmec world: San Lorenzo and La Venta.

San Lorenzo, flourishing between 1200 and 900 BCE, was the earliest Olmec center of power. Built on an artificially leveled plateau, it featured monumental architecture, drainage systems, and numerous colossal heads. San Lorenzo was a seat of political and religious authority, projecting the power of its rulers across the region.

When San Lorenzo declined, La Venta rose to prominence around 900 BCE. La Venta became a ceremonial capital, featuring one of the earliest known Mesoamerican pyramids, as well as altars, tombs, and sacred offerings. The site reveals the Olmecs’ mastery of urban planning and their ability to mobilize labor for monumental projects.

La Venta also illustrates the Olmecs’ spiritual devotion. Buried beneath its structures are caches of jade figurines arranged in ritual patterns, offerings of serpentine blocks, and mosaics that hint at complex ceremonial practices.

Together, San Lorenzo and La Venta embody the grandeur of the Olmecs, demonstrating their capacity for architectural innovation, political authority, and religious expression.

Trade and Cultural Exchange

The Olmecs were not an isolated people. They were active participants in long-distance trade networks that stretched across Mesoamerica.

From the Gulf Coast, they traded precious jade and obsidian, as well as ceramics and crafted ornaments. In return, they received resources not locally available, such as volcanic stone, quetzal feathers, and exotic shells. These exchanges not only enriched Olmec society but also spread their cultural influence far beyond their heartland.

Olmec motifs, styles, and practices have been found at distant sites, from the Valley of Mexico to Central America. This suggests that the Olmecs were not just local leaders but cultural pioneers whose ideas traveled widely, shaping the development of other civilizations.

Writing and Knowledge

One of the most debated aspects of Olmec culture is whether they developed a writing system. The discovery of artifacts such as the Cascajal Block—an inscribed tablet dated to around 900 BCE—suggests that the Olmecs may have experimented with symbols that could represent words or ideas.

If true, this would make the Olmecs among the earliest inventors of writing in the Americas. However, the evidence remains limited and contested. Whether these symbols were a fully developed script or proto-writing remains uncertain.

What is clearer is that the Olmecs possessed advanced knowledge of astronomy, mathematics, and timekeeping. Their alignment of ceremonial centers with celestial events suggests that they tracked the movements of the sun and stars, linking human ritual to cosmic cycles.

Decline and Legacy

By around 400 BCE, the great centers of the Olmecs had declined. San Lorenzo and La Venta were abandoned, and the civilization that had dominated the Gulf Coast for over a millennium faded into history. The reasons for their decline remain uncertain—environmental changes, shifting rivers, internal conflict, or external pressures may have played a role.

Yet the Olmecs did not vanish without leaving their mark. Their influence can be seen in the civilizations that followed: the Maya, Zapotec, Teotihuacanos, and Aztecs all inherited aspects of Olmec culture. The ballgame, pyramid building, ritual practices, and religious symbolism all trace their roots to the Olmec world.

In this sense, the Olmecs were not merely an early civilization but a foundational one—the “mother culture” of Mesoamerica. Even if they did not directly pass down every tradition, their innovations set the stage for centuries of cultural development.

Rediscovery of the Olmecs

For centuries after their decline, the Olmecs were forgotten. Their cities lay buried beneath jungle and earth, their colossal heads hidden from human eyes. It was not until the 19th and 20th centuries that archaeologists began to uncover the remnants of this remarkable civilization.

The discovery of the colossal heads astonished scholars and challenged assumptions about the development of civilization in the Americas. Over time, excavations revealed the extent of Olmec achievements, and today they are recognized as the first great civilization of the New World.

Yet mysteries remain. Who exactly ruled the Olmecs? What language did they speak? How did they view their gods, their cosmos, and their place in the world? Each new discovery brings us closer, but the Olmecs continue to guard many of their secrets.

Conclusion: The First Great Chapter of Mesoamerican Civilization

The Olmecs were pioneers. In the swamps and forests of the Gulf Coast, they built monumental centers, created enduring art, developed complex rituals, and laid the foundations of Mesoamerican culture. Their colossal heads, jade figurines, and ceremonial centers remind us of a people who transformed their environment into a stage for civilization.

Though they disappeared over two millennia ago, their influence endured, shaping the cultures that followed. The Maya, the Aztecs, and countless others carried forward their legacy, weaving it into the tapestry of Mesoamerican history.

To speak of the Olmecs is to speak of beginnings—the first great civilization of the Americas, whose vision and creativity opened the path for those who came after. They were America’s first great storytellers, architects, and dreamers, and through their monuments and symbols, their voice still whispers across the millennia: a reminder that even the earliest chapters of history hold lessons about human ingenuity, resilience, and the enduring quest to connect the human with the divine.