In a quiet lab at the University of Exeter, six ancient tools—silent for nearly two thousand years—are whispering their secrets once again. They were never meant to be artifacts. These were working instruments, crafted by skilled Roman hands, used to heal the broken, relieve suffering, and conduct surgeries long before modern medicine had a name. Now, through the lens of cutting-edge scanning technology, they are telling us how much those Roman medics knew—and how artfully they practiced their trade.

Buried for centuries near the Walbrook River in London, the instruments were discovered over 125 years ago. Today, they are held by the Devon and Exeter Medical Heritage Trust (DEMHT). But it wasn’t until recently, when the University of Exeter’s SHArD 3D Lab turned its microCT scanner toward them, that their story began to sharpen into view—layer by layer, atom by atom.

What emerged from those scans is not just a clearer picture of bronze and iron. It’s a rediscovery of ancient minds—how they healed, how they thought, and how they built tools of both beauty and precision.

Instruments for Healing in a Brutal World

It’s easy to think of the Roman Empire as brutal and unrelenting—a war machine that paved roads with conquest and history with blood. But beneath the sandals of soldiers and the columns of emperors, another story was unfolding: a deeply sophisticated system of medical knowledge. From battlefield wounds to intestinal ailments, Roman physicians developed tools and techniques that were not only practical, but in many cases, astonishingly advanced.

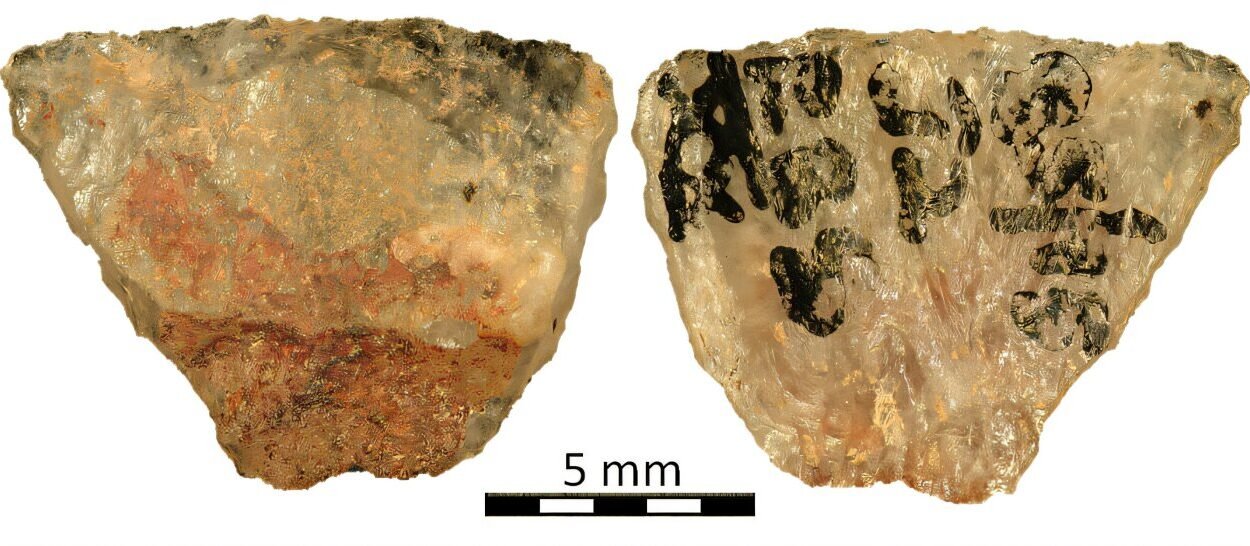

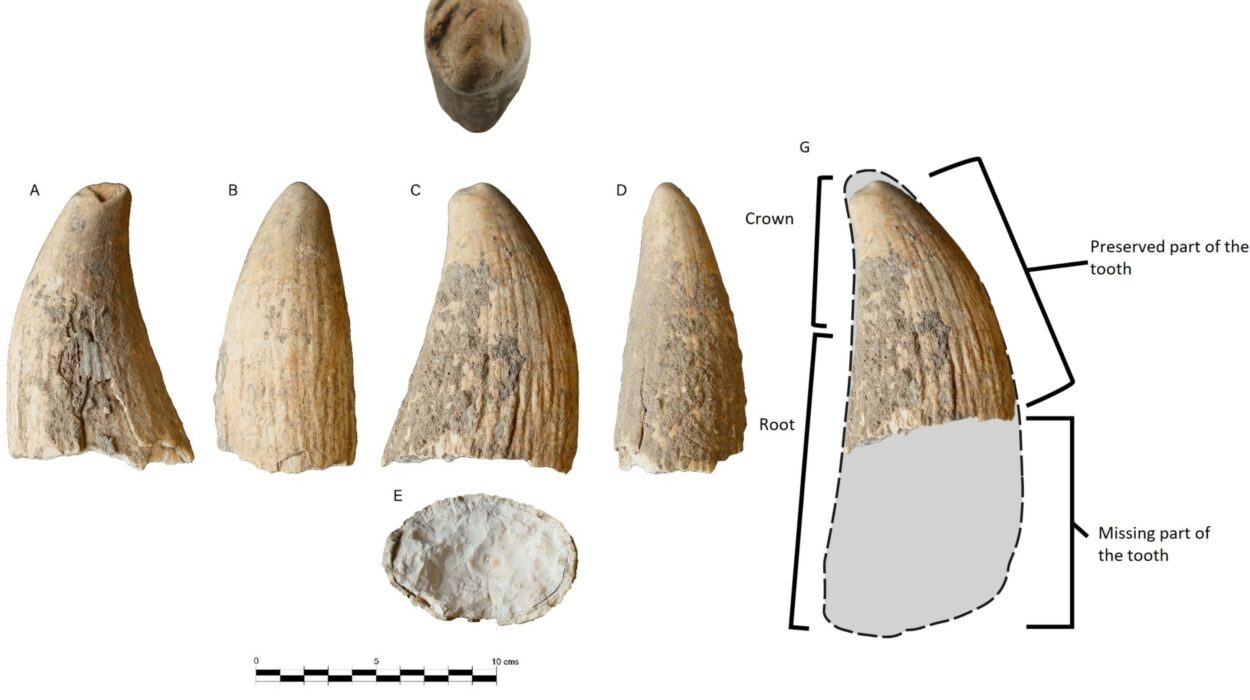

The instruments scanned by the Exeter team include a bronze scalpel handle, probes, a mixing spoon, and slender, tapered needles. Each piece is a marvel of design. With the scanner capable of revealing detail down to 0.05 millimeters, researchers could see things the human eye never could. Internal sockets where blades were inserted. Decorative scrollwork that wasn’t just aesthetic flair—it was functional, too.

Professor Rebecca Flemming, Leventis Professor of Ancient Greek Scientific and Technological Thought, describes the craftsmanship with reverence. The scalpel’s socket, she notes, was carefully designed to accept interchangeable iron blades. Over time, these blades could be replaced, while the elegant bronze handle—now the only surviving part—was reused. This wasn’t crude medicine. It was modular. Thoughtful. Sustainable.

What may look like tiny curls and scrolls on the handle are in fact intelligent design choices—crafted to allow better grip, easier blade replacement, and perhaps even to prevent slippage in a surgeon’s bloodied hands. These are the fingerprints of a civilization that saw medicine not only as science, but as art.

The Mind Behind the Metal

What exactly did Roman surgeons do with these tools? Professor Flemming, who has spent years decoding ancient medical texts from the Greek and Roman worlds, provides a window into their use. The scalpel, unsurprisingly, was employed for operations—sometimes minor, sometimes life-saving. One Roman medical writer described cutting open abscesses or removing growths under the skin. Bloodletting, widely practiced, was often done with blades like these. Not crude slashes, but precise incisions aimed at balancing the humors—the four bodily fluids Roman doctors believed controlled health.

The probes found with the scalpel had many purposes. They were used to explore wounds, navigate fistulae, and even assess bone fractures. But not all their uses were dramatic. Some were likely employed in more mundane acts of care, like clearing wax from ears or delivering medicinal ointments.

The spoon, too, wasn’t a dining utensil—it was likely a pharmacological companion, used to mix herbs, powders, and oils into pastes and salves. The needles could have stitched bandages or wounds, perhaps even skin itself. And behind each of these tasks stood a trained practitioner, familiar with the human body, its flaws, and its potential for healing.

These weren’t the acts of sorcery or guesswork. They were rooted in centuries of observation, documentation, and innovation. The Roman world absorbed and expanded on Greek medical traditions, and their empire allowed such knowledge to spread from the shores of Britannia to the sands of Syria. The result was a kind of medical standardization—an empire not just of roads and legions, but of scalpels and poultices.

Technology as Time Machine

Until now, many of these tools sat quietly behind glass or in museum storage, admired but unexamined. But the SHArD 3D Lab is changing that narrative. By using micro-computed tomography (microCT)—a scanning technology akin to medical CT scans but with microscopic resolution—researchers can look inside ancient objects without damaging them. The results are transformative.

With X-ray imaging, the team could peer through corroded layers and reconstruct what the tools originally looked like. They could identify manufacturing techniques, internal cavities, and even metal impurities that offer clues about how and where the tools were made. And perhaps most exciting of all, they can now 3D print exact replicas.

This means the tools can be held again—not the originals, but perfect recreations. Students, researchers, and museum visitors can feel what Roman surgeons felt. They can explore the weight, the balance, the shape—bringing the past into their hands, no longer a distant curiosity, but something real.

Dr. Carly Ameen, Director of the SHArD 3D Lab, emphasizes how this kind of interdisciplinary research—where archaeology meets engineering, and classics meets technology—can completely reshape how we study history. No longer are scholars limited to what they can see on a surface. They can now dive into the very atoms of an object, and come out with stories.

A Conversation Between Centuries

What emerges from this work is not just a clearer understanding of tools, but a clearer understanding of the people who used them. They were thoughtful, skilled, and practical. They worked in a world without anesthesia or antibiotics, but with a rich intellectual heritage that prized learning and healing. And they left behind more than bones and ruins—they left instruments of care.

Professor Flemming sees this project not just as an academic exercise, but as a powerful example of collaboration. The partnership between Exeter researchers and the DEMHT brings scholarship and public heritage into direct conversation. The tools are no longer passive relics—they are active participants in education and cultural memory.

And the implications go further. By better understanding how medical knowledge was transmitted through the Roman Empire—how tools and techniques traveled, evolved, and endured—we can gain insight into how science itself spreads. It reminds us that innovation isn’t always new. Sometimes, it’s ancient. Waiting. Sleeping in the soil, until the right light—and the right questions—wake it up.

What the Tools Still Teach Us

Standing in the lab, holding a 3D-printed scalpel once used nearly two millennia ago, one might feel a strange sense of connection. The surgeon who once held the original may have spoken Latin. He may have worked by lamplight. He may have faced pressure, failure, and heartbreak. But his goal—like the goal of today’s doctors—was the same: to heal.

That connection across centuries is what makes this research so powerful. The tools aren’t just archaeological finds. They are evidence of care. Of knowledge passed down. Of problems solved with creativity, precision, and grace.

In a world that often celebrates technological progress as something purely modern, it is humbling to see that much of what we now consider advanced had its beginnings long ago. And thanks to 3D scanning, those beginnings are no longer buried.

They are back, alive with purpose. And ready to teach again.