Long before concrete cities and digital maps, before written languages and national borders, Central Europe lay frozen under an unrelenting sheet of ice. From roughly 27,000 to 19,000 years ago, glaciers spread across vast stretches of the continent, transforming fertile valleys into lifeless tundra. Life in regions like the Swabian Jura—now part of southern Germany—seemed impossible. For decades, archaeologists believed that when the ice finally loosened its grip, it took thousands of years for humans to dare return.

But a new study from the University of Tübingen is challenging that long-held assumption. Deep in the limestone bones of the Lone Valley, two ancient sites—Vogelherd Cave and Langmahdhalde—have begun to tell a different story, one carved not just into stone, but into the very idea of what it means to endure.

The research, led by Benjamin Schürch, Dr. Gillian Wong, Dr. Elisa Luzi, and Professor Nicholas Conard, reveals that humans returned to this frozen landscape some 3,000 years earlier than previously thought. Far from being driven solely by climate change or shifting glaciers, these early pioneers seemed to possess a quiet resilience—and a desire to reclaim their place in a land that had once pushed them to the brink of extinction.

Rediscovering a Vanished World

It was long assumed that the Swabian Jura remained untouched by human hands until about 16,500 years ago, when the Ice Age began to loosen its hold and plant life slowly crept back across the landscape. That timeline, however, may have underestimated both the environment’s capacity to recover and humanity’s willingness to return.

Using state-of-the-art radiocarbon dating and decades of painstaking excavation, the Tübingen team has traced human activity in the region back to around 19,500 years ago—right at the edge of the glacial maximum. This means that modern humans ventured back into the icy heart of Europe much earlier than anyone imagined.

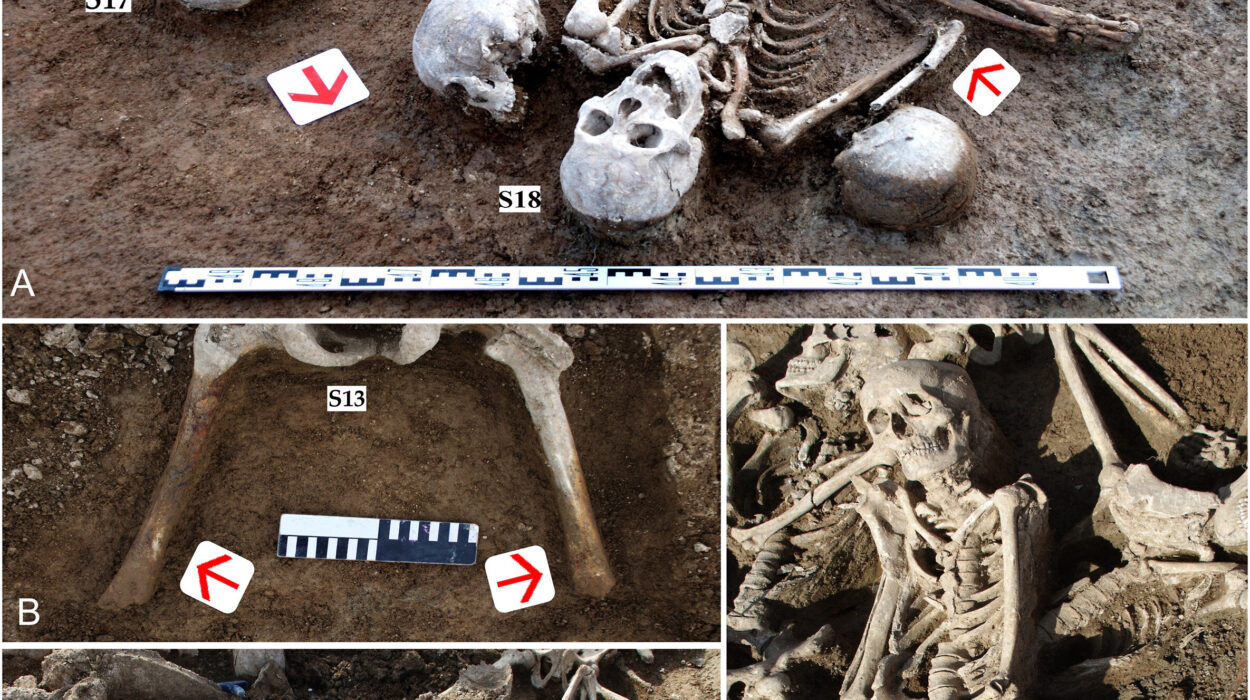

Inside Vogelherd Cave, archaeologists found traces of worked animal bones—tools carved by human hands. Just two kilometers away, the Langmahdhalde rock shelter offered another treasure trove: antler spearheads, stone tools, and microscopic fragments of ancient animal remains that told of a landscape still clawing its way out of the deep freeze. Together, the two sites offer a window not just into prehistoric migration, but into human adaptation itself.

A Cave That Remembered

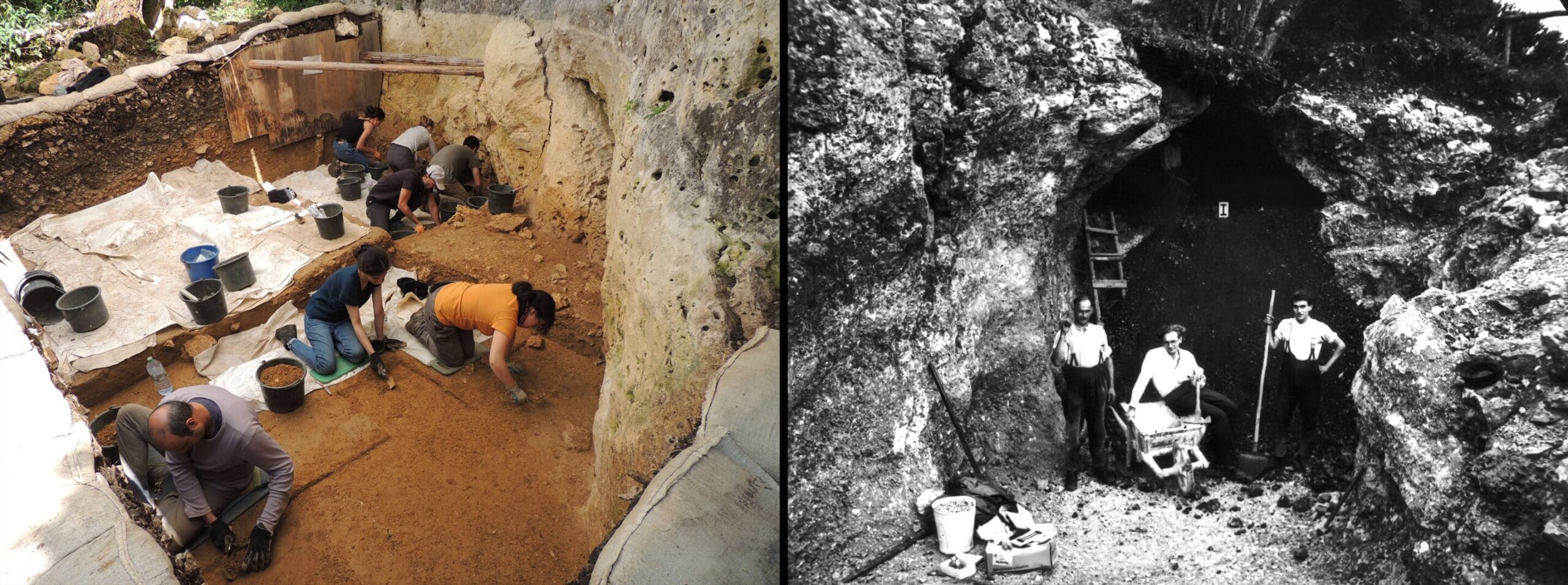

The Vogelherd Cave is no stranger to archaeological fame. First excavated in 1931 by Gustav Riek, it gained worldwide attention for its delicate animal figurines dating back over 40,000 years. These carvings—rendered in mammoth ivory—belong to the Aurignacian culture, one of the earliest expressions of symbolic thought in Europe.

But beneath those celebrated layers, deeper in the sediment, something else waited—forgotten and unglamorous, but no less profound. Traces of the Magdalenian culture, a later Ice Age society known for its practical stone and bone tools, had gone overlooked. These were not works of art, but tools of survival—chisels for scraping hides, antler points for hunting reindeer and horse.

Now, with fresh excavations and modern methods, researchers have identified Magdalenian material at strikingly early dates. Among the bones and stone flakes, they’ve found a timeline that pushes the human presence in the region back to nearly the height of the Ice Age itself.

The story the cave now tells is one of return and resilience. Humans were not just waiting for the warmth to come back—they were navigating a changing, uncertain world, trying to reestablish life at the margins of the habitable Earth.

Langmahdhalde: A Precision Time Capsule

While Vogelherd offered rich finds, its early excavations lacked detailed documentation. For the Tübingen team, the nearby Langmahdhalde rock shelter became the ideal companion site. Excavated between 2016 and 2024 under the careful supervision of Professor Conard, every layer at Langmahdhalde was recorded with modern precision. There, organic remains found in direct contact with Magdalenian stone tools provided crucial dating evidence.

Using carbon-14 analysis, a method that relies on the predictable decay of radioactive carbon isotopes, researchers established that humans had occupied Langmahdhalde between 17,900 and 17,000 years ago—only a few centuries after the earliest Magdalenian traces in Vogelherd. This proximity in both geography and time allowed scientists to cross-reference cultural materials from both sites, strengthening the argument for early recolonization.

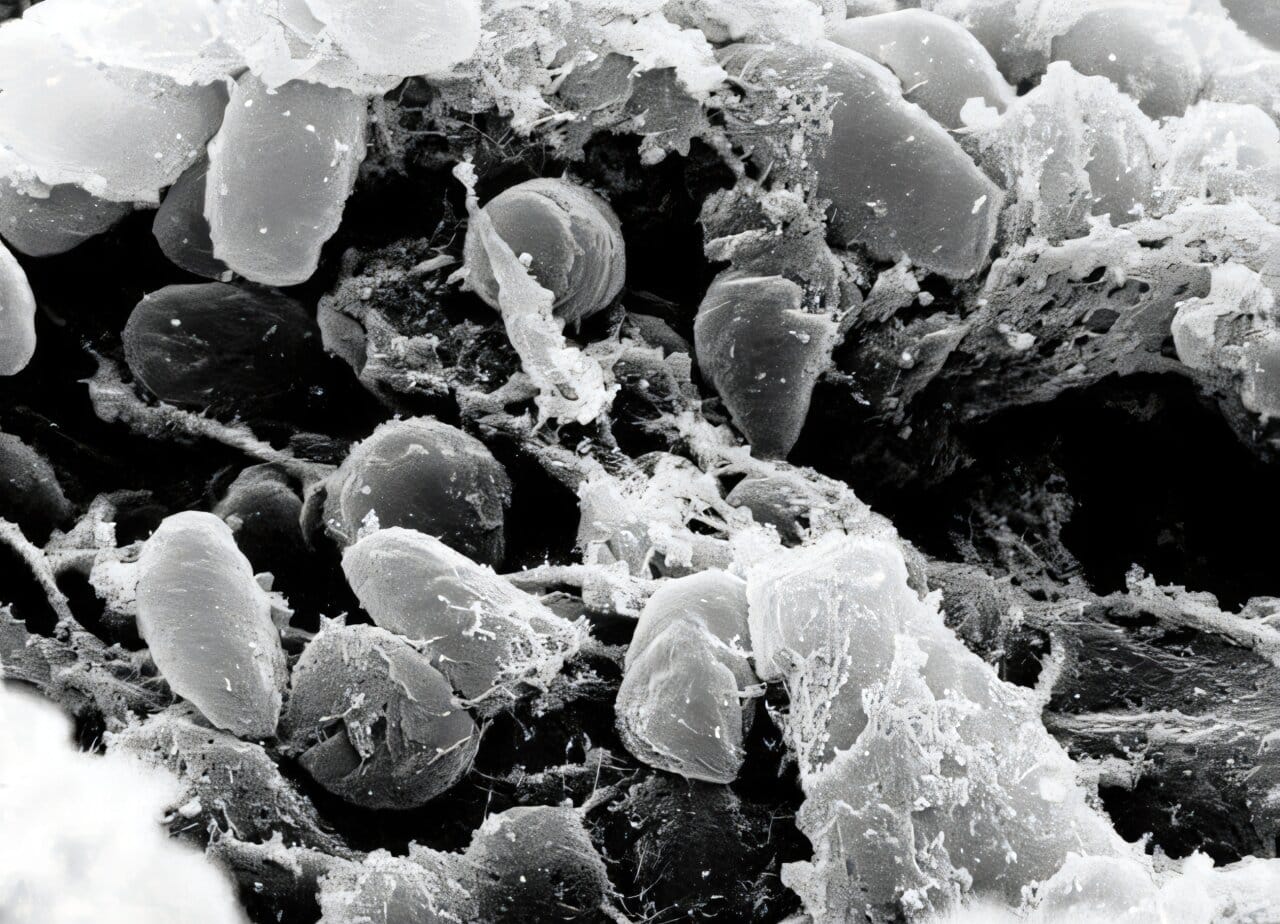

Microfauna—tiny animal bones left behind by predators and natural processes—helped reconstruct the climate of the time. These fragments told of a world in flux: not quite frozen, but far from warm. Conditions were harsh, but life—animal and human—was adapting.

Returning Before It Was Safe

Why would people come back so early, when the world was still cold, resources scarce, and survival uncertain?

One possibility is that the region never fully lost its human presence. Even during glacial peaks, temporary shelters and seasonal hunting camps may have dotted the landscape. These were not cities or villages, but waypoints in a nomadic life—evidence of people who knew how to follow the animals, find shelter in the rocks, and survive on the edge of desolation.

Dr. Gillian Wong, one of the study’s co-authors, believes the answer lies in both culture and climate. “Although modern humans had repopulated the Swabian Jura in isolated cases at the end of the Ice Age,” she explains, “they only settled permanently in the region again around 16,500 years ago.” This suggests that early returns were tentative, experimental—pioneers testing the land, trying to see if home was still possible.

These early forays were not yet a migration in full force. They were the first sparks of repopulation, flickering against the cold.

What Tools Can Tell Us

Beyond their dates and locations, the tools found at Vogelherd and Langmahdhalde tell us something intimate about the people who used them. Spear points carved from antler speak to a sophisticated knowledge of materials. Stone scrapers used to prepare hides reveal domestic tasks and the rhythms of daily life. These were not mindless wanderers—they were craftspeople, hunters, and thinkers.

The Magdalenian culture, to which these tools belong, spanned much of Western Europe during the later stages of the Ice Age. Known for its specialized hunting technology and impressive bone craftsmanship, the Magdalenian way of life represented a leap forward in how humans related to their environment.

By tying these tools to specific radiocarbon dates, the researchers weren’t just building a timeline—they were reconstructing a way of life. One that combined memory, adaptation, and hope in equal measure.

The Broader Human Story

This study, now published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, doesn’t just rewrite a regional chapter of European prehistory—it speaks to the broader human story. It reveals that our ancestors were not passive observers of climate. They were agents of resilience, pressing forward into the cold with fire in their hands and stories in their minds.

It also highlights the importance of continued excavation and re-analysis. Sites once thought to be fully explored—like Vogelherd—can still surprise us when we return with fresh questions and better tools. The past, like the Earth itself, often reveals its secrets in layers.

As Professor Conard and his team continue their work, each flake of stone and fragment of bone becomes part of a larger, living mosaic: not just of when humans returned to central Europe, but how they never truly left.

In the end, these ancient explorers weren’t just survivors of the Ice Age—they were the ancestors of every story that followed.

Reference: Benjamin Schürch et al, Evidence for an earlier Magdalenian presence in the Lone Valley of southwest Germany, Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2024.104632