In a quiet, forgotten crypt beneath Milan—a space once filled with whispered prayers and the shuffle of mourning feet—two bodies lay in silence for centuries. Their flesh had long since surrendered to time, but their brains remained eerily preserved. And within those ancient, shriveled tissues, modern science has discovered a secret that challenges what we thought we knew about the history of drugs in Europe.

In a groundbreaking study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, a team of biomedical and pharmacological experts from the University of Milan, in collaboration with the Foundation IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico di Milano, has revealed something extraordinary: traces of active coca plant compounds in the brains of two individuals buried in the 17th century.

Long before the synthetic refinement of cocaine in the 19th century or its controversial rise to prominence in modern times, it appears that at least some Europeans were already using coca in its raw, natural form. Not as a medicine. Not as a prescribed remedy. But seemingly, as a recreational escape.

Echoes from the Andes

To understand how remarkable this discovery is, we need to travel across both space and time.

For thousands of years, Indigenous peoples in western South America chewed the leaves of the coca plant—Erythroxylum coca—to fight fatigue, hunger, and altitude sickness. To them, coca was a sacred gift from the earth, a plant deeply entwined with ritual, survival, and spirituality. It was not a drug in the modern sense but a symbol of harmony with the natural world.

European colonizers, fascinated by the coca leaf’s energizing properties, began exporting samples back home. But processing it into cocaine hydrochloride, the potent white powder we associate with the modern drug, didn’t happen until the 1800s.

So how, then, did two poor Milanese citizens come to have coca compounds in their brains more than 200 years earlier?

Unearthing a Mystery

The answers lay buried beneath the Ca’ Granda hospital, one of Milan’s oldest medical institutions. Its crypt was a resting place for patients who died in the nearby hospital—a mix of the city’s poor, ill, and abandoned. Over the centuries, the crypt became a repository of bones, secrets, and overlooked history.

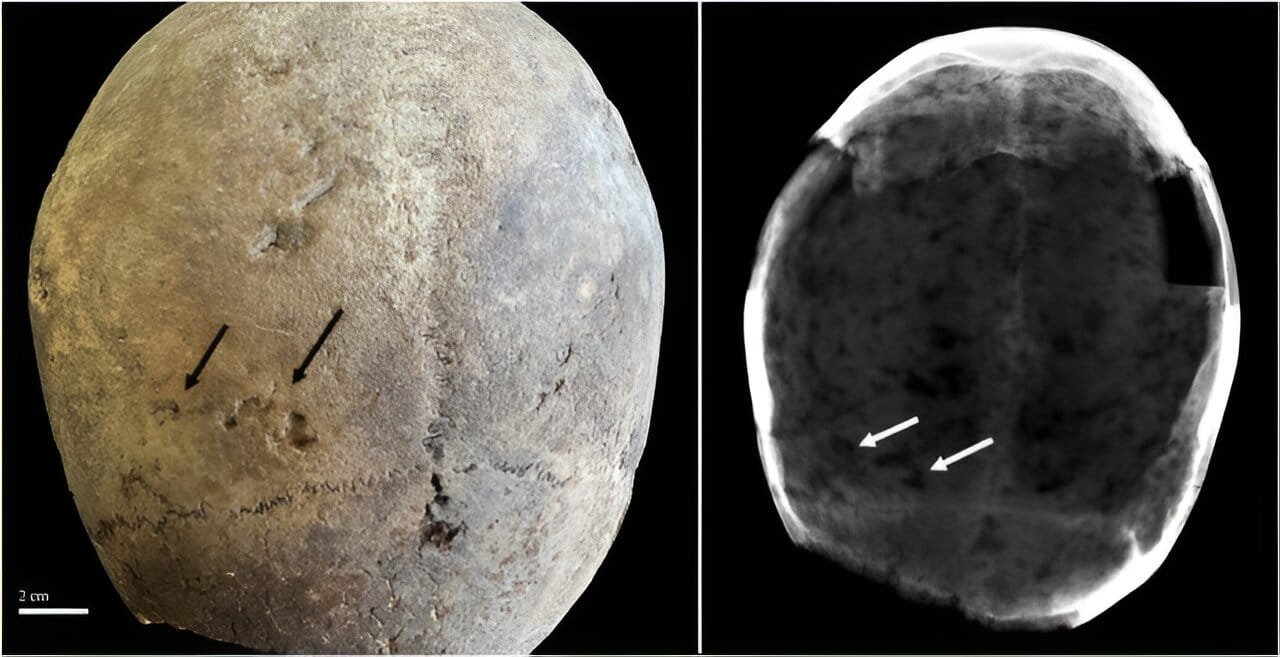

But unlike most skeletal remains, two individuals were found naturally mummified, their internal organs astonishingly intact. The research team took samples from the preserved brain tissue—a rare opportunity in archaeological science—and analyzed them using cutting-edge chemical detection methods.

The results were astonishing: both individuals had retained active metabolites of the coca plant. These weren’t just ancient herbal traces. They were biological fingerprints, proving that the two people had chewed coca leaves before their deaths.

More curiously, there was no mention of coca or cocaine in the hospital’s historical medical records. No evidence it had been prescribed or used as a treatment. These people hadn’t been given coca as medicine.

They’d sought it out on their own.

Not Rich, Not Famous—Just High

One of the more humbling aspects of this discovery is the social status of the two individuals. They weren’t nobles, physicians, or wealthy traders. Their burial conditions suggested they were poor—perhaps even destitute.

That detail changes everything.

It suggests that coca leaves were neither rare nor expensive. These weren’t luxury goods trickling down from elite apothecaries. They were, at least in this corner of 17th-century Milan, available to everyday people. That raises remarkable possibilities: Was there a small, underground market for coca? Was it brought over in trade routes by sailors or merchants? Had it quietly integrated into the lower classes as a casual stimulant, much like tobacco or alcohol?

There are no definitive answers—yet. But the very existence of this evidence demands we rethink the tidy timelines we’ve drawn about the history of drug use in Europe.

A Cultural Blind Spot

Historians have long viewed the 17th century as a time of alchemy, religious fervor, plague, and scientific awakening. It was an era where superstition and medicine clashed daily, where coffee was just arriving in European ports, and tobacco had begun its slow seduction of the continent. But until now, cocaine—or its ancestral leaf—had no place in this story.

This new discovery challenges that omission. It introduces a new, gritty subplot to the narrative: that Europe’s romance with psychoactive substances began earlier and more secretly than we thought. And it suggests that the desire to alter consciousness—to escape, to energize, to feel different—is not just a modern affliction, but a deeply human one, stretching back through the centuries.

The Brain as a Time Capsule

What’s perhaps most poetic about this discovery is where the evidence was found: in the brain. For a long time, archaeologists have relied on bones and teeth to study the past. But brain tissue, rarely preserved, is like finding a time capsule that still whispers.

The coca metabolites weren’t found in stomach contents or hair—which degrade quickly. They were inside the neural tissue itself, where the mind once lived. That means the chemical traces weren’t incidental. They were metabolized, processed, and internalized.

This was not passive exposure. It was a conscious act of consumption.

It is haunting to imagine those individuals—perhaps exhausted from labor, stressed by illness, or simply seeking a moment of escape—placing coca leaves in their mouths, letting the bitter alkaloids soak into their gums, and feeling the subtle shift in energy and perception.

Their reasons may be lost to history, but their choice is recorded in chemistry.

Why It Matters Today

At first glance, this may seem like a curiosity—an academic footnote. But its implications ripple far beyond the crypt.

Modern debates about drug use often frame substances like cocaine as recent problems born from industrialization or globalization. We think of them as products of chemistry labs and criminal empires. But this study reminds us that the roots of drug use are older and more personal.

People have always sought ways to soothe pain, fight fatigue, enhance mood, or simply feel something different. Whether through coca leaves in 1600s Milan, opium in ancient China, or energy drinks today, the underlying drive remains the same.

Understanding that drive, in historical context, may help us build more humane, informed policies in the present. Addiction isn’t just a failure of will. It’s a pattern embedded in human behavior. A whisper passed down through generations.

A Door to New Questions

This study opens more doors than it closes.

Were these individuals part of a larger group using coca? Was the trade of coca leaves more widespread than previously known? Could more evidence lie waiting in other crypts, catacombs, or forgotten graves? Could letters, diaries, or merchant records hint at an invisible culture of recreational coca use in early modern Europe?

The researchers have illuminated just one darkened corridor of history. Others remain untouched. But with every such discovery, our image of the past becomes less sanitized, more nuanced—and more human.

Final Thoughts from the Crypt

Two nameless individuals, long gone, have now told us something profound. In their brains, preserved by time and chance, we’ve found proof of something quietly radical: that the desire to alter one’s mind, to taste the edge of euphoria or push away exhaustion, is not new. It is as old as we are.

They didn’t leave behind diaries or monuments. But they left us molecules. And in them, a message:

The past was not as different as we think. And sometimes, the dead know things we’ve forgotten.

Reference: Gaia Giordano et al, Forensic toxicology backdates the use of coca plant (Erythroxylum spp.) in Europe to the early 1600s, Journal of Archaeological Science (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.jas.2024.106040