For centuries, the writing of the ancient Maya remained one of the great puzzles of human history. Visitors who wandered through the ruined cities of Central America—amid towering stone pyramids, ball courts, and intricately carved stelae—were confronted with thousands of strange symbols etched into stone, painted on pottery, or inscribed in books of bark paper. These mysterious glyphs seemed to hold the key to understanding one of the most advanced civilizations of the ancient world. Yet for generations, their voices were silent, their meaning hidden, their messages locked away like secrets in an undeciphered code.

To speak of Mayan writing is to enter a tale of discovery, persistence, and the triumph of human curiosity. It is the story of how scholars, artists, linguists, and even outsiders once dismissed the script as decorative or mystical. It is also the story of how, piece by piece, that silence was broken. Today, we can read the words of Mayan kings and scribes, hear the echoes of their prayers and histories, and glimpse their thoughts across more than a thousand years.

The Mayan script is not only a system of communication; it is a window into a vanished world. It tells us how the Maya conceived of time, power, gods, war, and the cosmos. It reveals their dynasties and their struggles, their triumphs and their tragedies. To decode Mayan writing is not simply to solve a linguistic puzzle—it is to restore the voices of a civilization that shaped Mesoamerica for over two millennia.

The Birth of a Unique Writing System

The Maya were not the only people in the ancient Americas to develop writing. The Olmecs, often called the “mother culture” of Mesoamerica, produced some of the earliest glyphs around 900 BCE. Later, the Zapotecs and the Mixtecs crafted their own scripts. But it was the Maya, flourishing between 250 and 900 CE, who created the most elaborate, flexible, and enduring system of writing in the New World.

Mayan writing was both visual art and linguistic genius. Unlike alphabetic systems such as English or Greek, the Mayan script combined logograms (symbols representing words or ideas) with syllabic signs (symbols representing sounds). This made it capable of expressing both meaning and speech in exquisite detail. A single inscription might weave together abstract imagery, phonetic spelling, and wordplay, capturing both the literal and the poetic.

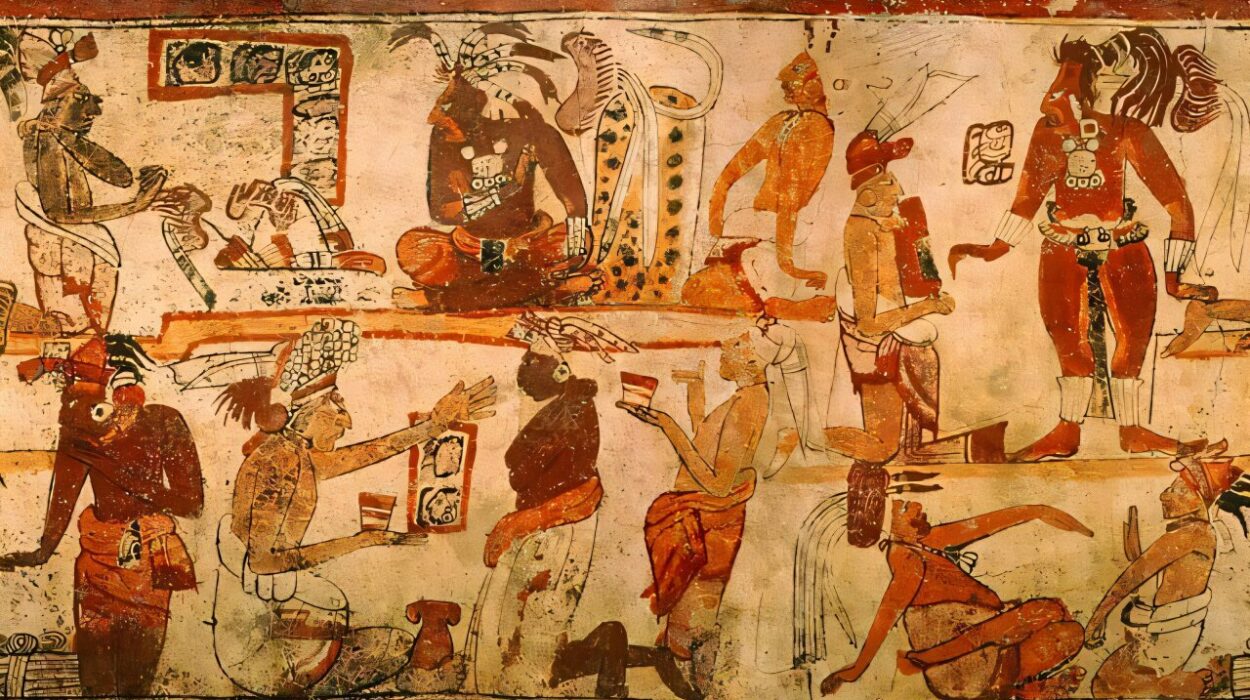

Carved into limestone monuments, painted onto ceramic vessels, and written in codices on bark-paper pages, Mayan writing flourished across the Yucatán Peninsula, Guatemala, Belize, and Honduras. It was a living script, produced by a class of trained scribes who often signed their work, proudly identifying themselves as “painters” and “writers.” For the Maya, writing was not just a practical tool but a sacred act, linking humanity to the divine.

The Structure of the Script

At first glance, Mayan glyphs look like intricate, almost whimsical drawings—faces, animals, hands, abstract forms, all flowing together like a mosaic. But beneath the artistry lies a sophisticated system. Scholars today recognize over 800 distinct glyphs, though not all were used at the same time or place.

The script combines two main elements:

- Logograms represent whole words, often with iconic images. For example, a jaguar head might represent the word balam (“jaguar”).

- Syllabic signs represent syllables, such as ka, ku, or ma, allowing scribes to spell words phonetically.

By blending these, the Maya could write with both efficiency and precision. A scribe might use a single logogram for “jaguar” or spell it out syllabically as ba-la-ma. Sometimes they combined both, using the syllables as phonetic “hints” to clarify the reading of a logogram. This flexibility made Mayan writing uniquely expressive.

Text was usually arranged in paired columns, read left to right and top to bottom in a zigzag pattern. This elegant layout gave Mayan inscriptions their characteristic block-like appearance, each cluster of glyphs forming a self-contained “glyph block.”

The Role of Writing in Maya Civilization

For the Maya, writing was not a tool of the masses but a privilege of the elite. Literacy was concentrated among scribes, priests, and rulers, who used the script to preserve history, perform rituals, and legitimize power. Writing was carved into stelae that celebrated kings, painted onto murals that depicted cosmic narratives, and written into codices that tracked the movement of the stars.

The Maya were obsessed with time, and their writing reflects this passion. They developed complex calendar systems, recording dates with astonishing precision. Some inscriptions document events that occurred centuries before they were written, connecting rulers with mythological pasts that stretched back to the creation of the world.

Yet Mayan writing was not limited to the grand stage of kings and gods. Painted ceramics reveal lively scenes of feasting, dancing, and even humor, often accompanied by captions identifying individuals or narrating the action. In these moments, Mayan writing brings us close to the human side of a civilization—its wit, its artistry, its everyday life.

The Silence After the Conquest

The arrival of the Spanish conquistadors in the 16th century was catastrophic for Mayan culture. Cities were abandoned, populations decimated by warfare and disease, and the written tradition nearly erased. Spanish missionaries, particularly Bishop Diego de Landa, viewed Mayan books as works of paganism and ordered their destruction.

Only four codices survived this cultural holocaust—the Dresden, Madrid, Paris, and Grolier codices—each a fragile testament to what was lost. These rare books contain astronomical tables, rituals, and calendars, offering a glimpse of Mayan intellectual achievements. But the vast majority of Mayan writing vanished in flames, taking with it libraries of knowledge accumulated over centuries.

For the next several hundred years, the meaning of Mayan glyphs remained locked away. Scholars speculated endlessly about the script, but progress was slow. Some thought it was purely symbolic, representing ideas rather than speech. Others dismissed it as decorative art without linguistic content. The Maya themselves, many of whom still spoke Mayan languages, were left disconnected from their ancestral texts, their own history obscured.

The Long Struggle to Decipher

The modern story of decoding Mayan writing is a drama filled with false starts, rivalries, and breakthroughs. In the 19th century, explorers like John Lloyd Stephens and Frederick Catherwood brought back detailed drawings of Mayan ruins, igniting interest in the mysterious glyphs. But their meaning remained elusive.

It was Bishop Diego de Landa, ironically, who left behind the first crucial clue. In the 1560s, he attempted to document the Mayan language and created what he thought was an “alphabet.” Though flawed, his notes preserved fragments of phonetic values that would later prove invaluable.

The real breakthrough came in the 20th century. Scholars such as Tatiana Proskouriakoff demonstrated that inscriptions were not merely mythological but historical, recording the lives of real rulers. Later, the Russian linguist Yuri Knorozov argued that the script was phonetic and used Landa’s “alphabet” as a key to cracking the syllables. His ideas, initially controversial, eventually transformed the field.

By the late 20th century, epigraphers like Linda Schele, David Stuart, and others built on these foundations, piecing together more and more of the language. Today, we can read much of the script with confidence. Entire dynasties, once silent, now speak again through their inscriptions.

The Voices of the Maya Restored

Thanks to these efforts, Mayan texts have been brought back to life. We now know the names of kings and queens, their battles, their alliances, and their rituals. We can trace the rise and fall of city-states like Tikal, Copán, Palenque, and Calakmul. We can even read poems, prayers, and mythological narratives that reveal how the Maya viewed their gods and their place in the cosmos.

One of the most extraordinary aspects of Mayan writing is its ability to blend the earthly and the cosmic. An inscription might record a king’s accession to the throne while simultaneously linking it to a celestial event or a creation myth. Time for the Maya was not linear but cyclical, and their writing reflects this intricate worldview.

On pottery, we find texts that label food vessels, identify their owners, or narrate mythological tales. On murals, we see dialogue captions that give voice to painted figures. On monuments, we witness political propaganda carefully crafted to legitimize dynasties. Together, these writings form a mosaic of Mayan civilization, intimate and grand at once.

The Mayan Script Today

The story of Mayan writing does not end with its decipherment. It continues today in the hands of modern Maya communities and scholars who are reclaiming their written heritage. Efforts are underway to teach Mayan glyphs in schools, revive the art of writing, and connect contemporary Maya speakers with the ancient script of their ancestors.

For many, this is more than scholarship—it is cultural renewal. After centuries of colonial erasure, the ability to read Mayan inscriptions is a powerful act of identity and resilience. What was once silent is now spoken again, not only in academic circles but in the communities whose ancestors created it.

Why Mayan Writing Matters

Decoding Mayan writing has done more than solve an intellectual puzzle—it has reshaped our understanding of the ancient world. The Maya were once imagined as peaceful astronomers or mystical dreamers, their ruins shrouded in mystery. But their writings reveal a far more complex reality: city-states locked in rivalries, rulers engaged in diplomacy and warfare, a society both brilliant and turbulent.

At the same time, Mayan writing has given us rare access to the human voice of antiquity. To read a king boast of his victories, or a scribe proudly sign his name, or a calendar predict the turning of the heavens, is to encounter the past in its own words. Few things are as powerful as hearing history speak for itself.

Conclusion: The Living Script of the Maya

Mayan writing is one of humanity’s greatest achievements, a script that captures the depth of a civilization and the creativity of the human mind. Its story is one of survival against overwhelming odds: burned by conquest, silenced for centuries, and nearly forgotten, yet reborn through scholarship and resilience.

Today, as we walk through the ancient plazas of Tikal or gaze at the stelae of Copán, we no longer see silent stones. We see pages of a history book, voices carved in stone and painted in color, waiting to be read. The Maya, once thought lost to time, speak again in their own words.

And perhaps this is the true power of Mayan writing—that it reminds us the past is never entirely gone. It waits patiently, inscribed in symbols, until someone cares enough to listen. In decoding Mayan script, we have not only uncovered history—we have reawakened a civilization.