In the windswept desert of Middle Egypt, amid the silent ruins of the once-vibrant city of Amarna, archaeologists have uncovered a small object that carries with it a surprising voice from the past. It is not gold, nor a jeweled treasure, nor a statue of a forgotten god, but something far more modest: a perforated cow toe bone. Yet, when held to the lips, this humble artifact sings—a piercing whistle that may once have echoed across the desert more than three thousand years ago.

This remarkable discovery was made by Michelle Langley, Anna Stevens, and Christopher Stimpson as part of the Amarna Project, under the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research at the University of Cambridge. Their study, published in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, suggests that this small bone whistle offers a rare glimpse into the soundscape of everyday life in ancient Egypt—an aspect of history often overshadowed by the monumental and the divine.

The City of Akhenaten

To understand the significance of this find, we must step back into the reign of Pharaoh Akhenaten, one of ancient Egypt’s most enigmatic rulers. Around 1347 BC, Akhenaten broke with centuries of tradition, abandoning the old gods in favor of Aten, the sun disk. In a bold and controversial move, he founded a new city dedicated to Aten—Akhetaten, now known as Amarna.

For a brief generation, this desert city thrived, home to royal palaces, grand temples, and vibrant communities of artisans, priests, and laborers. But when Akhenaten died around 1332 BC, the city was abandoned, its sun-worshipping experiment swiftly erased by successors who restored the old gods. What remained was a ghost city, preserved in fragments of stone and clay, awaiting rediscovery by archaeologists millennia later.

Since the 1970s, excavations at Amarna have peeled back layers of this forgotten world. Unlike many sites in Egypt that emphasize kings and temples, Amarna is exceptional because it preserves the lives of ordinary people—workers, guards, and families whose stories rarely survive in the archaeological record. It was in this context that the bone whistle emerged.

The Stone Village and Its Hidden Artifact

The whistle was found in the Stone Village, a small, isolated settlement near Amarna. Along with the nearby Workmen’s Village, it likely housed the stonecutters and laborers who carved the tombs of the royal cemetery. Unlike the grand avenues of the city proper, these settlements were enclosed and heavily guarded, with roadways and checkpoints that controlled movement in and out.

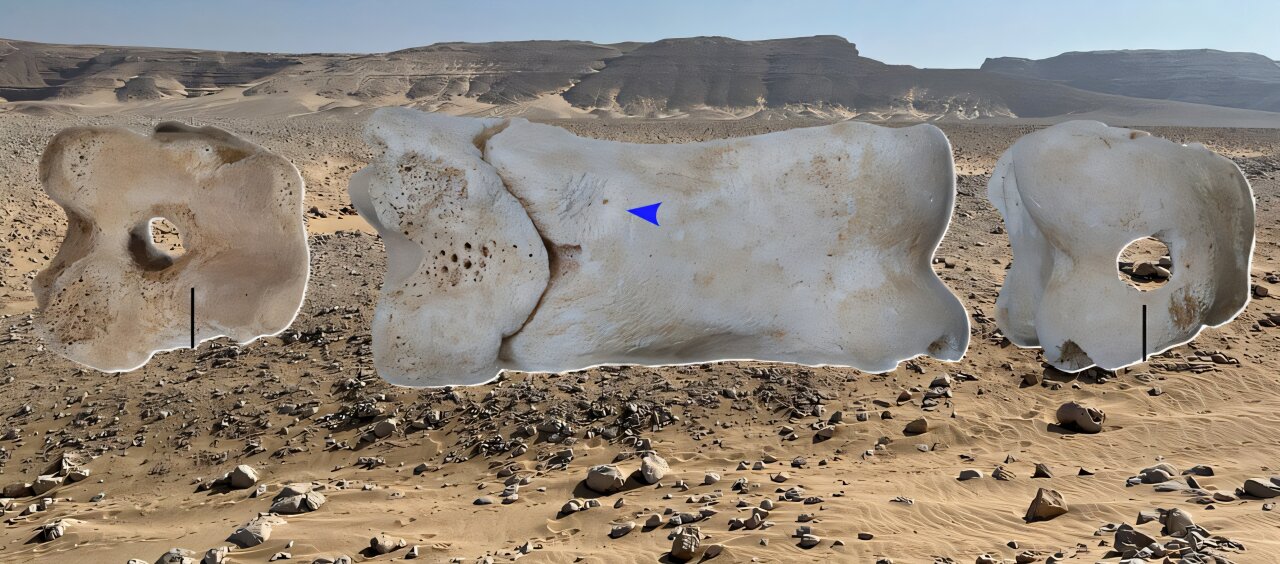

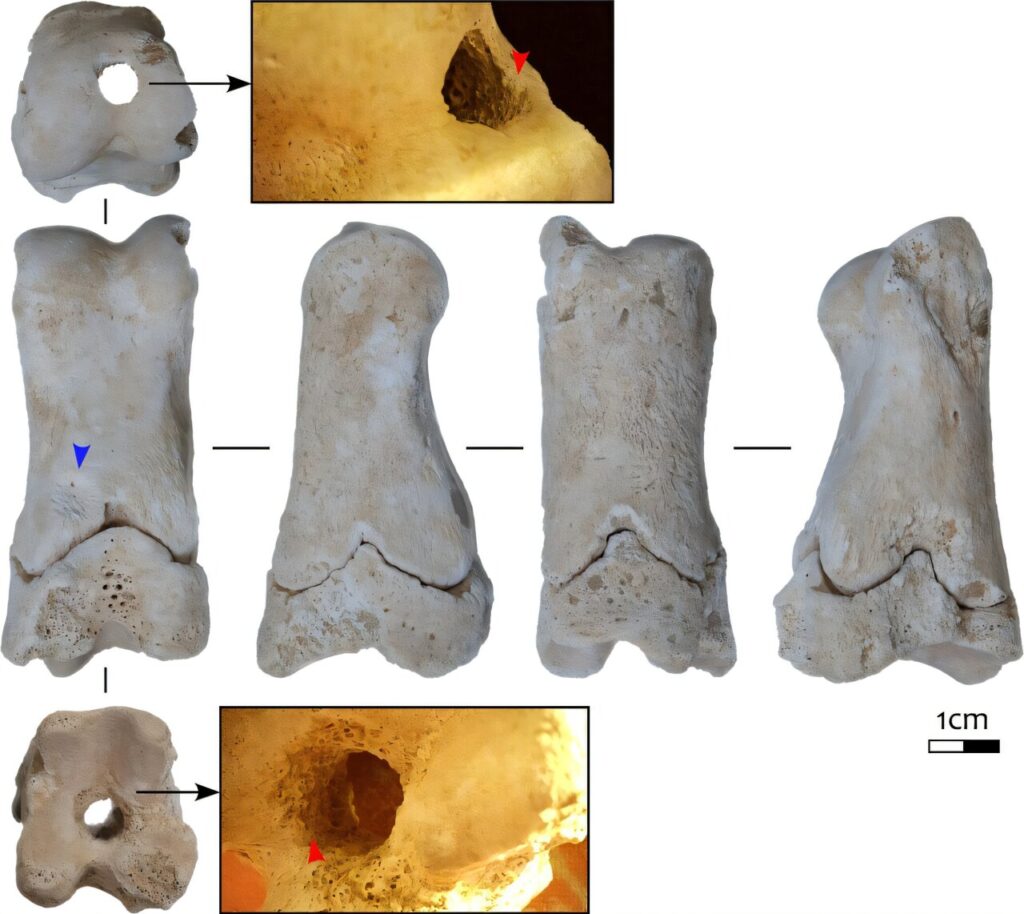

One such checkpoint included two structures: Structure II, likely a guard post, and Structure I, which may have served as storage or sleeping quarters for guards. From this unassuming Structure I came a single artifact: the cow phalanx bone, carefully perforated.

At first glance, it puzzled the researchers. Ungulate phalanges had often been used in antiquity for ornaments, game pieces, handles, or figurines. But this bone did not match the usual wear or modifications seen in those contexts. It seemed to serve another purpose altogether.

Giving Voice to the Silent Bone

To test their ideas, the researchers recreated the artifact using modern cattle phalanges. To their surprise, when blown into, the bone produced a loud, clear whistle, capable of carrying sound across open space. This suggested that the Amarna bone was not decorative or symbolic but functional.

Placed within the guarded setting of the Stone Village, the whistle begins to tell a story. Perhaps it was used by guards to signal one another across checkpoints. Perhaps it served as a warning device, a call to attention, or even a way to regulate movement in and out of the settlement.

Although direct evidence for such uses is scarce, the experiment revealed that ancient Egyptians may have relied on practical, everyday sound-making tools alongside the more elaborate musical instruments we see in temple art and museum collections.

The Hidden Soundscapes of Ancient Egypt

One of the most intriguing aspects of this discovery lies in what it reveals about sound in the ancient world. As Langley notes, the study of “soundscapes” in ancient Egypt is still in its infancy. Tomb paintings, ostraca, and temple engravings often depict musicians with harps, flutes, and sistrums, and archaeologists have uncovered a number of such instruments. Yet whistles, simple as they are, remain absent from the artistic and archaeological record.

This absence raises fascinating questions. Were whistles too ordinary to be immortalized in art? Were they so commonplace that no one thought to depict them? Or were they tools reserved for practical functions—signals, commands, or warnings—rather than for music or ritual?

The Amarna whistle hints at a layer of Egyptian life we rarely glimpse: the everyday soundscape of workers, guards, and villagers, whose tools of communication were not adorned in gold but carved from bone.

The Fragility of Everyday Life

Discovering such an object is a triumph not only of archaeology but of preservation. Sites like Amarna are vulnerable to time and the elements. Open-air settlements are often less well preserved than tombs, with termites, erosion, and weather reducing fragile organic materials to dust. Bone, in particular, is easily destroyed in Egypt’s harsh climate.

This makes the survival of the Amarna whistle all the more remarkable. It is a reminder that the history we inherit is skewed toward the durable and the spectacular—the golden masks, the towering obelisks, the stone temples that withstand centuries. Meanwhile, the simpler tools of daily life, though once essential, vanish more easily from the record.

As Langley explains, archaeology has long focused on the elite, dazzled by their monumental legacies. Yet it is the everyday tools—undecorated, utilitarian, and modest—that may tell us more about how most people lived. The Amarna Project, by uncovering entire communities, bridges this gap, offering a window into the ordinary alongside the extraordinary.

Echoes of an Ordinary Past

The bone whistle of Amarna may seem insignificant compared to the treasures of Tutankhamun or the colossi of Ramses. But in its smallness lies its power. It is an artifact that reminds us that history is not only the story of kings and gods but also of workers, guards, and villagers whose lives left quieter traces.

Perhaps a guard once raised this whistle to his lips, summoning a fellow worker from across the desert wind. Perhaps its sharp sound echoed through the narrow passages of the Stone Village, a signal of duty, warning, or routine. Whatever its use, the whistle carried the voice of someone who lived, worked, and died in Amarna—a voice we can now faintly hear again after three millennia of silence.

Toward a Fuller Picture of Ancient Egypt

Langley and her colleagues hope that this discovery is only the beginning. Other bone artifacts from Amarna, long overlooked in museum collections, may yet reveal more about the tools and practices of ordinary Egyptians. Each one has the potential to reshape our understanding of a culture too often defined only by its most dazzling achievements.

The whistle is a reminder that archaeology is not just about the spectacular but about the subtle. It asks us to listen more closely to the fragments of history, to pay attention to the overlooked and the ordinary. Because in those whispers, we find not only objects but people—their lives, their routines, their ingenuity, and their humanity.

The Whistle That Still Speaks

In the end, the Amarna bone whistle is not simply an artifact. It is a sound preserved in silence, a link between the present and the distant past. It tells us that the ancient Egyptians were not only builders of temples and worshippers of gods but also people who signaled, called, and communicated in the rhythms of everyday life.

Three thousand years after it was last used, this simple bone carries with it a profound truth: history is not only written in monuments of stone but also in the breath of a whistle, carried on the desert wind.

More information: Michelle C. Langley et al, First Identification of Bone Whistle‐Use in Dynastic Egypt, International Journal of Osteoarchaeology (2025). DOI: 10.1002/oa.70026