When we think of ancient civilizations, images of towering pyramids in Egypt or monumental ziggurats in Mesopotamia often come first. Yet, buried beneath layers of earth in what is now Pakistan and northwest India lies a civilization that spoke not in colossal monuments but in the quiet brilliance of its cities. The Indus Valley Civilization, flourishing around 2600–1900 BCE, remains one of humanity’s most extraordinary experiments in urban living. Its story is not carved into temples or inscribed with proclamations of kingship. Instead, it is written into the streets, drains, bricks, and layouts of cities that were astonishingly advanced for their time.

To explore the urban planning of the Indus Valley is to step into a world where practicality met vision, where collective well-being outweighed ostentation, and where a people long forgotten still whisper their ingenuity through brick-lined avenues. In the heart of Mohenjo-daro and Harappa, we find cities that were centuries ahead of their time, embodying principles that modern planners still struggle to master today.

The Cradle of a Forgotten Civilization

The Indus Valley Civilization, also known as the Harappan Civilization, flourished along the fertile plains of the Indus River and its tributaries. With a population estimated at over five million at its peak, it was one of the world’s three great cradles of civilization, alongside Mesopotamia and Egypt. Yet, unlike its contemporaries, the Indus people left behind no grand palaces, no kingly tombs, no boastful inscriptions declaring conquests. What they did leave was something subtler, yet perhaps more profound: cities that reflect an extraordinary collective vision.

These cities were not accidental clusters of houses but meticulously planned urban centers. They reveal a society deeply invested in order, cleanliness, efficiency, and fairness. The ruins suggest a culture that valued its people enough to create environments where sanitation, safety, and equality were priorities—a radical notion for 4,000 years ago.

Grids Before Their Time

One of the most striking features of Indus Valley cities is their grid-based layout. Long before Hippodamus of Miletus earned fame as the “father of urban planning” in ancient Greece, Harappan planners were already designing their settlements with streets intersecting at right angles.

Mohenjo-daro, one of the largest cities of the civilization, showcases this geometry with a clarity that feels almost modern. Main streets ran north-south, intersected by east-west roads, creating rectangular city blocks. This pattern was no accident. It speaks to careful surveying, centralized authority, and a sophisticated understanding of spatial organization.

The grid was not only aesthetic—it was functional. The uniformity of streets allowed for efficient movement of people and goods. It ensured fairness, as plots of land were distributed with remarkable equality. Unlike many ancient civilizations, where elites claimed grand estates while the poor huddled in chaos, the Indus Valley’s cities reveal a degree of balance in housing. Whether rich or modest, dwellings adhered to similar designs and were interwoven into the same planned neighborhoods.

Bricks That Built a Civilization

At the foundation of this urban brilliance lay the humble brick. Indus builders used standardized baked bricks, typically in a ratio of 1:2:4 (height, width, length). This uniformity was revolutionary. It meant that every builder, every mason, every project used materials that fit seamlessly together.

Standardized bricks reflect more than technical knowledge—they suggest centralized governance, shared norms, and large-scale cooperation. They also ensured durability. Many structures, from walls to wells, have withstood thousands of years, bearing witness to the resilience of Harappan engineering.

In comparison, other civilizations often used sun-dried mud bricks that eroded over time. The Indus choice of fired bricks reveals foresight: they invested labor in permanence, creating cities meant not just for the present but for generations to come.

Water, Sanitation, and the Miracle of Drains

Perhaps the most astonishing aspect of Indus Valley urban planning lies in its water management and sanitation systems. While much of the world lived without organized sewage until the modern era, Harappan cities had drains, baths, and water systems that would not reappear on such a scale until Roman times.

Each house, regardless of size, was connected to a sophisticated drainage system. Wastewater from kitchens and baths flowed into covered street drains, which were regularly cleaned. Manholes and inspection holes were strategically placed along these drains—an idea so advanced that it mirrors features of today’s sewage infrastructure.

Public wells dotted the cities, ensuring access to clean water. Private wells within homes were also common, suggesting a concern for both community and household needs. The presence of large reservoirs and water tanks, like the famed Great Bath of Mohenjo-daro, underscores the significance of water in civic and perhaps even ritual life.

This emphasis on cleanliness was extraordinary. It indicates not only technical skill but also a cultural mindset that valued hygiene, health, and dignity. In a world where diseases often spread unchecked through contaminated water, the Harappans had devised a system to mitigate such risks, securing healthier lives for their people.

The Great Bath: A Monument of Community

Among the most iconic structures of the Indus Valley is the Great Bath at Mohenjo-daro. Measuring about 12 meters long and 7 meters wide, with carefully sealed brickwork to prevent leakage, it remains one of the oldest public water tanks ever discovered.

The purpose of the Great Bath is debated. Some scholars believe it was used for ritual purification, while others see it as a civic amenity. Regardless, its design reflects a society that valued collective spaces. Unlike the towering temples of Mesopotamia or the pyramids of Egypt built to glorify rulers, the Great Bath was a place for people—a communal site that brought citizens together.

Its construction required not just technical mastery but also shared values. It was not the project of a single king but the embodiment of a society that placed importance on collective well-being and perhaps spiritual equality.

Storage, Trade, and the Pulse of Economy

Urban planning in the Indus Valley was not only about housing and sanitation—it also supported a vibrant economy. Large granaries have been unearthed at Harappa and Mohenjo-daro, suggesting centralized storage of surplus grain. These facilities were positioned near riverbanks and citadels, indicating careful planning in food distribution and flood protection.

The civilization thrived on trade, both internal and long-distance. Indus seals, inscribed with undeciphered symbols and often adorned with animal motifs, have been found as far as Mesopotamia, pointing to commercial connections across vast distances. The layout of cities facilitated this exchange. Wide streets, uniform weights and measures, and storage facilities all hint at a highly organized system of commerce.

Urban planning was thus intertwined with economic planning. The cities were not static—they pulsed with the rhythms of trade, agriculture, and craft production, sustained by the infrastructure designed by visionaries whose names we will never know.

Social Harmony Written in Streets

What is perhaps most moving about Indus Valley urban planning is the sense of social ethos it conveys. Unlike many ancient civilizations, there is little evidence of sharp divides between palaces for rulers and hovels for the poor. Instead, the cities reveal a degree of egalitarianism.

While variations in house size existed, even smaller dwellings were equipped with access to wells and drains. The absence of ostentatious royal tombs or grandiose temples suggests that wealth and power were not flaunted in stone. Instead, resources appear to have been channeled into collective benefits—water systems, sanitation, granaries, and public baths.

This does not mean the Indus Valley Civilization was without hierarchy or authority. But the urban design reflects priorities that emphasized community welfare over individual glory. In this sense, their cities still resonate as models of civic-mindedness.

Challenges of Floods and Climate

The Indus Valley Civilization’s urban brilliance did not exist in isolation from nature. The cities were often built along rivers, which brought both fertility and danger. Seasonal floods shaped the rhythms of life, and urban planners adapted with raised citadels, elevated platforms, and careful site selection.

Yet, despite their ingenuity, climate change and shifting river patterns may have contributed to the civilization’s decline. Archaeological evidence suggests that around 1900 BCE, monsoon patterns weakened, rivers dried up or shifted course, and agricultural productivity faltered. Urban centers gradually dwindled as people moved eastward toward the Ganges plains.

Here lies a poignant reminder: even the most sophisticated urban systems remain vulnerable to the forces of nature. The Indus planners were visionaries, but they could not fully conquer the unpredictability of the environment.

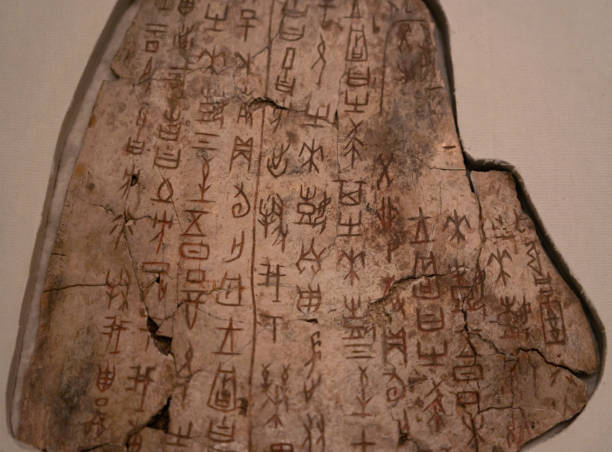

A Civilization Without a Voice

One of the enduring mysteries of the Indus Valley is its script. Inscribed on seals, pottery, and tablets, these symbols remain undeciphered despite decades of research. Without written records, we can only speculate about the political organization, religious beliefs, or personal stories of the Harappans.

This silence makes their urban planning all the more powerful. In the absence of kings’ names or epic tales, their legacy is their cities. Streets, bricks, and drains become their narrative, whispering of a people who chose to invest in community, equality, and foresight.

Lessons for the Modern World

The urban planning of the Indus Valley is not just an archaeological curiosity—it offers profound lessons for today. In an age when cities grapple with pollution, overcrowding, and inequity, the Harappan model stands as a beacon.

Their emphasis on sanitation underscores the importance of public health infrastructure. Their use of standardized building materials highlights the value of regulation and efficiency. Their grid layouts reflect the need for organization, while their egalitarian designs remind us that cities should serve all, not just the privileged few.

Perhaps most importantly, their story warns us of fragility. Climate change and environmental shifts played a role in their decline, just as they threaten modern urban centers. The Indus people teach us that sustainable planning must account for nature’s power, for no city is immune to the forces of the Earth.

Conclusion: The Quiet Brilliance of the Indus Valley

The Indus Valley Civilization may not dazzle with towering monuments or heroic inscriptions, but its greatness lies in something deeper: a vision of urban life that prioritized order, hygiene, equity, and community. Their cities were not built to glorify rulers but to serve people. Their bricks, drains, and grids remain silent testaments to a collective genius that was centuries ahead of its time.

Today, as our world becomes increasingly urbanized, the Harappans still have much to teach us. They remind us that true greatness in a civilization is not measured by the height of its monuments but by the livability of its cities, the dignity of its people, and the foresight of its planners.

In the dust of Mohenjo-daro and Harappa, we glimpse a civilization that, though lost, continues to guide us. Its whispers echo across millennia: that to build wisely is to build for all, and that the future of cities lies not in domination but in harmony.