For centuries, the Shroud of Turin has captivated the hearts and minds of believers, skeptics, scientists, and artists alike. Kept in the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist in Turin, Italy, this linen cloth bears the faint image of what appears to be a crucified man. Many believe it to be the burial shroud of Jesus of Nazareth, a holy relic touched by the divine. Others argue it is a masterful medieval forgery—one of the most elaborate works of religious art ever created.

Now, a new scientific study has added a modern twist to this ancient enigma. Using open-source digital tools and 3D modeling, researchers have tested how a real human body—or a low-relief artistic sculpture—would leave an imprint on cloth. Their conclusion? The image on the Shroud of Turin might not be the natural contact image of a body at all, but something more deliberate. Something artistic.

The Clash of Carbon and Controversy

The mystery of the Shroud is not just spiritual—it’s a scientific battleground. In 1989, a highly publicized radiocarbon dating study dated the Shroud’s fibers to between 1260 and 1390 AD. For many, this was the nail in the coffin for its authenticity, aligning its origin with a known period of relic-making fervor during the Middle Ages.

But that conclusion didn’t sit well with everyone. In 2005, chemist Raymond Rogers challenged the validity of the sample used in the carbon dating. He suggested that the fibers tested were taken from a portion of the cloth that had been repaired in the 16th century—meaning the rest of the Shroud might be much older.

The plot thickened again in 2022 when a new test using Wide Angle X-ray Scattering (WAXS)—a technique sensitive to structural changes in materials—dated a single thread from the Shroud to the first century AD. If accurate, that would place it much closer to the time of Jesus. But this method is not widely accepted yet, and the results have been met with both excitement and skepticism.

Amid all the dating drama, one key question has remained largely unanswered: How was the image actually made?

Blood, Body, or Brushstrokes?

While science has offered competing dates for the Shroud, another fundamental issue is the anatomy of the image itself. A forensic study published a few years ago noted inconsistencies in the blood patterns visible on the Shroud. If a man had truly been laid flat on the cloth after crucifixion, the patterns of blood and body shape should follow predictable flow and imprint paths. But they didn’t.

The researchers went so far as to say that the bloodstains were “totally unrealistic,” implying that the blood may have been applied after the fact—not left behind by a real body, but painted or transferred artistically. That hypothesis continues to split the scholarly community.

But what if we stopped asking when the image was made and instead asked how it was formed? Enter the world of digital modeling.

A New Era of Historical Investigation

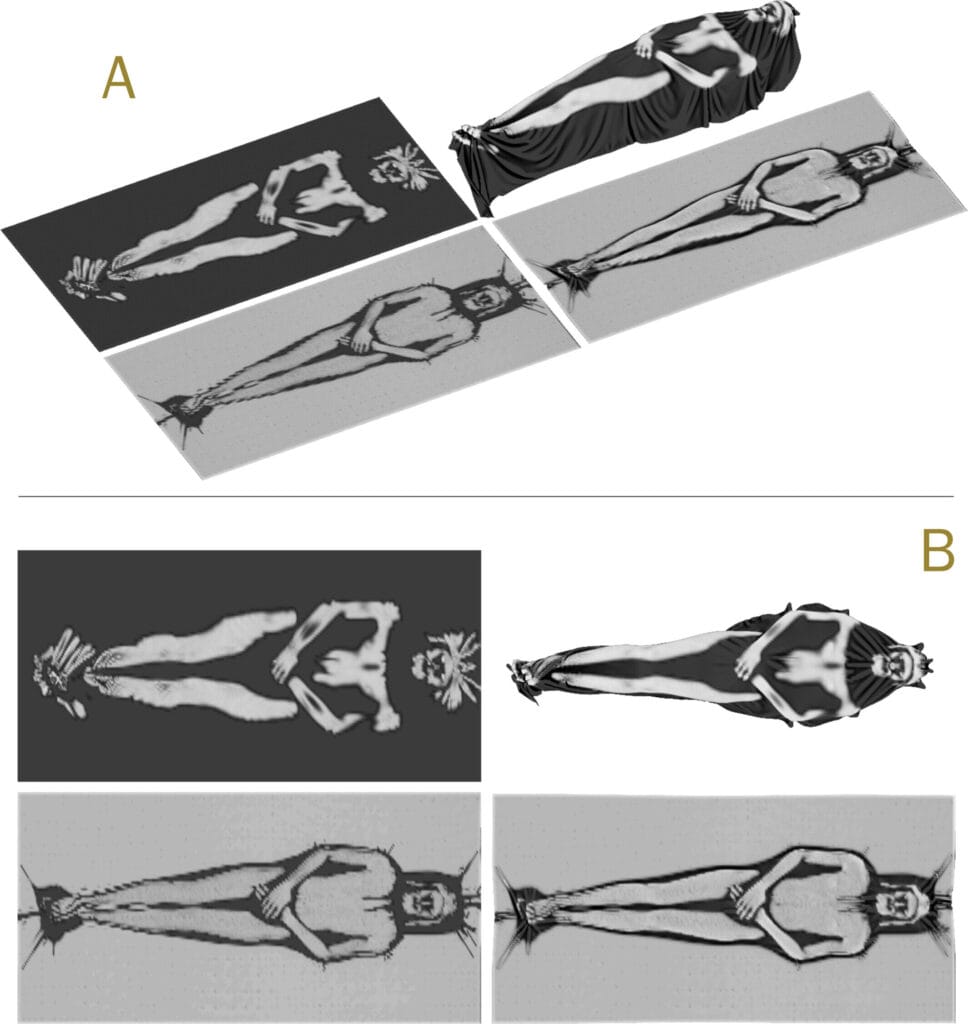

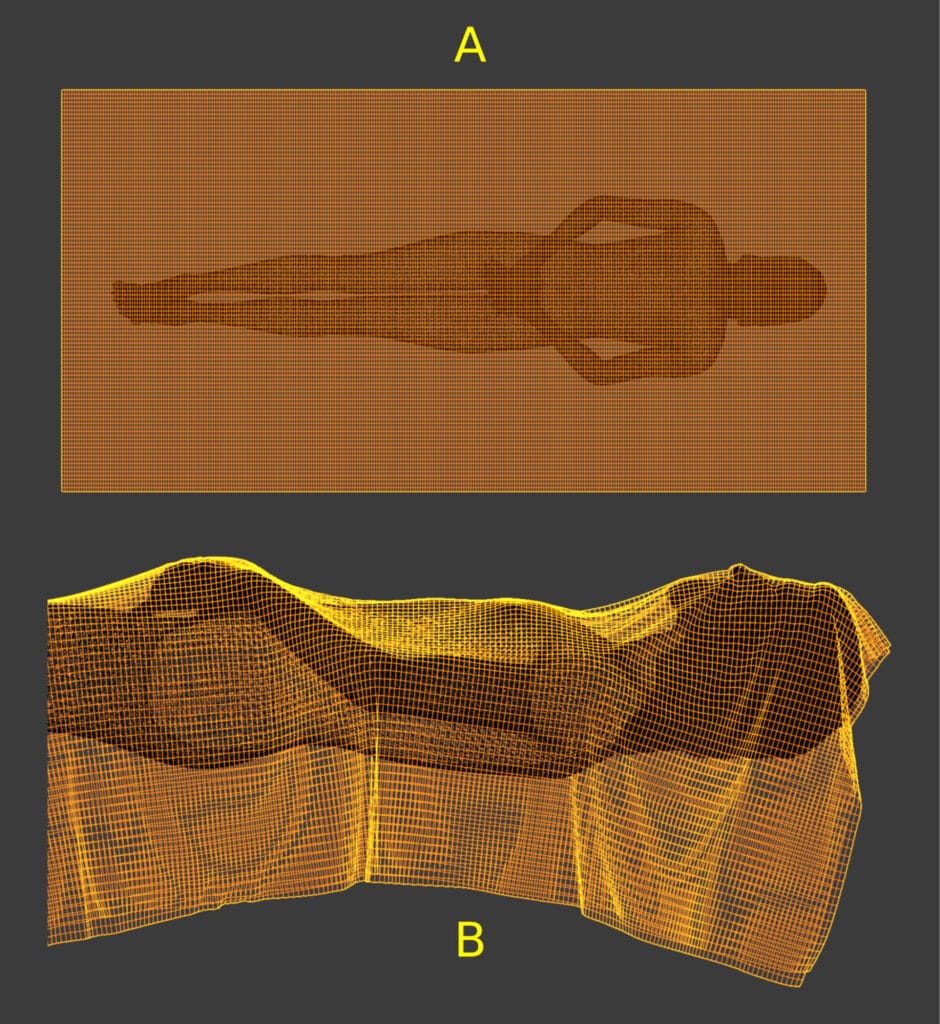

In a recent study published in Archaeometry, researcher Cicero Moraes employed software tools like MakeHuman, Blender, and CloudCompare—commonly used in animation and 3D graphics—to digitally simulate what kind of image results when cloth is laid over a human body versus a low-relief sculpture.

The principle is simple but revealing: When a 2D sheet like cloth wraps around a 3D object, the resulting image appears stretched or distorted—especially along curved surfaces like shoulders or faces. This is known as the Agamemnon Mask effect, named after a Bronze Age funerary mask that appears unnaturally wide and flat, likely due to the way it was removed or created.

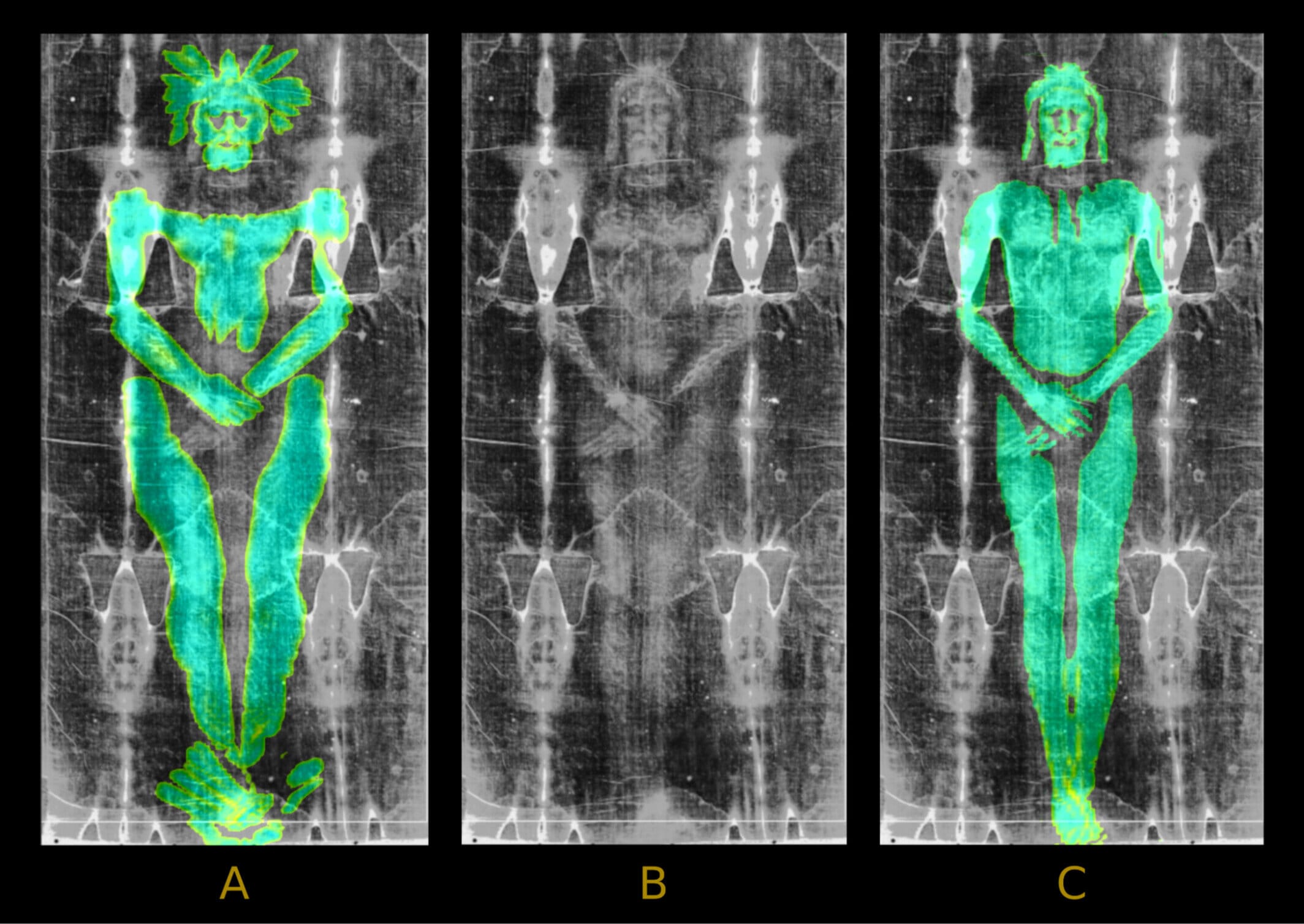

Moraes’ team found that when a virtual cloth was laid over a 3D human figure and then digitally “flattened” into a 2D image, the resulting imprint was wider and more distorted than what we see on the actual Shroud. However, when the same cloth was modeled over a low-relief sculpture—think of a very shallow, flattened statue—the resulting imprint closely matched the proportions and visual characteristics of the Shroud’s image.

In other words, the Shroud’s image behaves more like an artistic relief than a real body imprint.

The Case for a Medieval Masterpiece

This new insight doesn’t date the Shroud definitively, but it does lend strong support to one theory: that the image may have been created as an intentional artistic rendering, rather than as a passive imprint from a wrapped body.

Low-relief art was common during the medieval period, especially in religious contexts. Artists had the skill—and the motive—to create a compelling and deeply spiritual image using techniques designed to mimic divine intervention. The Shroud’s ghostly image, visible only in certain lighting or from a distance, could have been designed precisely to inspire awe and reverence.

In his paper, Moraes wrote, “The contact pattern generated by the low-relief model is more compatible with the Shroud’s image, showing less anatomical distortion and greater fidelity to the observed contours, while the projection of a 3D body results in a significantly distorted image.”

That conclusion challenges a core assumption: that the Shroud’s image was the result of a human body. Instead, it might have been carefully crafted to look like the product of a miraculous event.

Science Meets Spirituality—Again

To be clear, this new study doesn’t claim to prove or disprove the Shroud’s authenticity. It doesn’t say whether it wrapped Jesus or not. But it does ask us to look closer—literally and figuratively—at how we interpret what we see.

Whether it’s radiocarbon dating, X-ray scattering, forensic blood analysis, or 3D modeling, science continues to interrogate the Shroud’s mysteries. And each time, we come closer not necessarily to consensus, but to deeper questions. Why was the Shroud created? For whom? With what tools and intent?

Moraes invites others to join the inquiry: “This work not only offers another perspective on the origin of the Shroud of Turin’s image but also highlights the potential of digital technologies to address or unravel historical mysteries, intertwining science, art, and technology in a collaborative and reflective search for answers.”

A Cloth, A Question, A Conversation

In the end, the Shroud of Turin is more than a relic. It’s a canvas of human curiosity. To believers, it may be a sacred echo of the divine. To historians, it’s a testament to medieval devotion or deception. To scientists, it’s a puzzle at the intersection of matter and myth.

And in every pixel of the digital reconstructions, in every line of carbon data, in every thread of linen tested under microscopes, the Shroud asks us to look again—not just at the cloth, but at ourselves.

Perhaps the real mystery isn’t whether the image is divine or deceptive. Perhaps the mystery is why it continues to captivate us after so many centuries.

Because whether created by miracle or man, the Shroud of Turin is undeniably powerful. And the search for truth—like the image itself—is both haunting and enduring.

More information: Cicero Moraes, Image Formation on the Holy Shroud—A Digital 3D Approach, Archaeometry (2025). DOI: 10.1111/arcm.70030