In the soft, starlit hush of a desert night, when the sky seems like a vast ocean overhead, one can almost imagine a goddess stretching her limbs across the heavens, her skin dusted with stars, her breath a cosmic whisper. To the ancient Egyptians, this was not a flight of fancy—it was cosmology. And in the figure of Nut (pronounced “Noot”), the sky-goddess, they gave form to the dome above, turning myth into meaning, and the universe into sacred narrative.

Now, more than 3,000 years later, this celestial tradition has found an unlikely observer: an astrophysicist from the University of Portsmouth. Associate Professor Dr. Or Graur, a modern-day seeker of cosmic truths, has unearthed what may be a rare, visual depiction of the Milky Way in ancient Egyptian art—a shimmering link between science and myth, astronomy and Egyptology.

The Scholar Who Looked Up

Dr. Graur’s journey into the mythological cosmos began not in a lab or observatory, but in a museum with his daughters. As he tells it, it was the wide-eyed curiosity of his children that first drew his attention to the enigmatic image of a star-speckled woman arched across a sarcophagus. “They kept asking to hear stories about her,” he recalls. And so, the image of Nut—naked, arched over the earth god Geb, stars twinkling across her body—became a doorway into a forgotten relationship between the heavens and humanity.

With a background in astrophysics and a growing fascination with mythology, Dr. Graur began an in-depth study that would straddle two disciplines: the modern science of galaxies and the ancient wisdom embedded in Egyptian religion. It was a bold endeavor—decoding religious iconography through the lens of astrophysics.

In his latest paper, published in the Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, Dr. Graur presents an interpretation that could reshape how we understand the way ancient Egyptians saw the night sky—and perhaps even how they imagined the Milky Way itself.

Nut: The Night Empress of the Cosmos

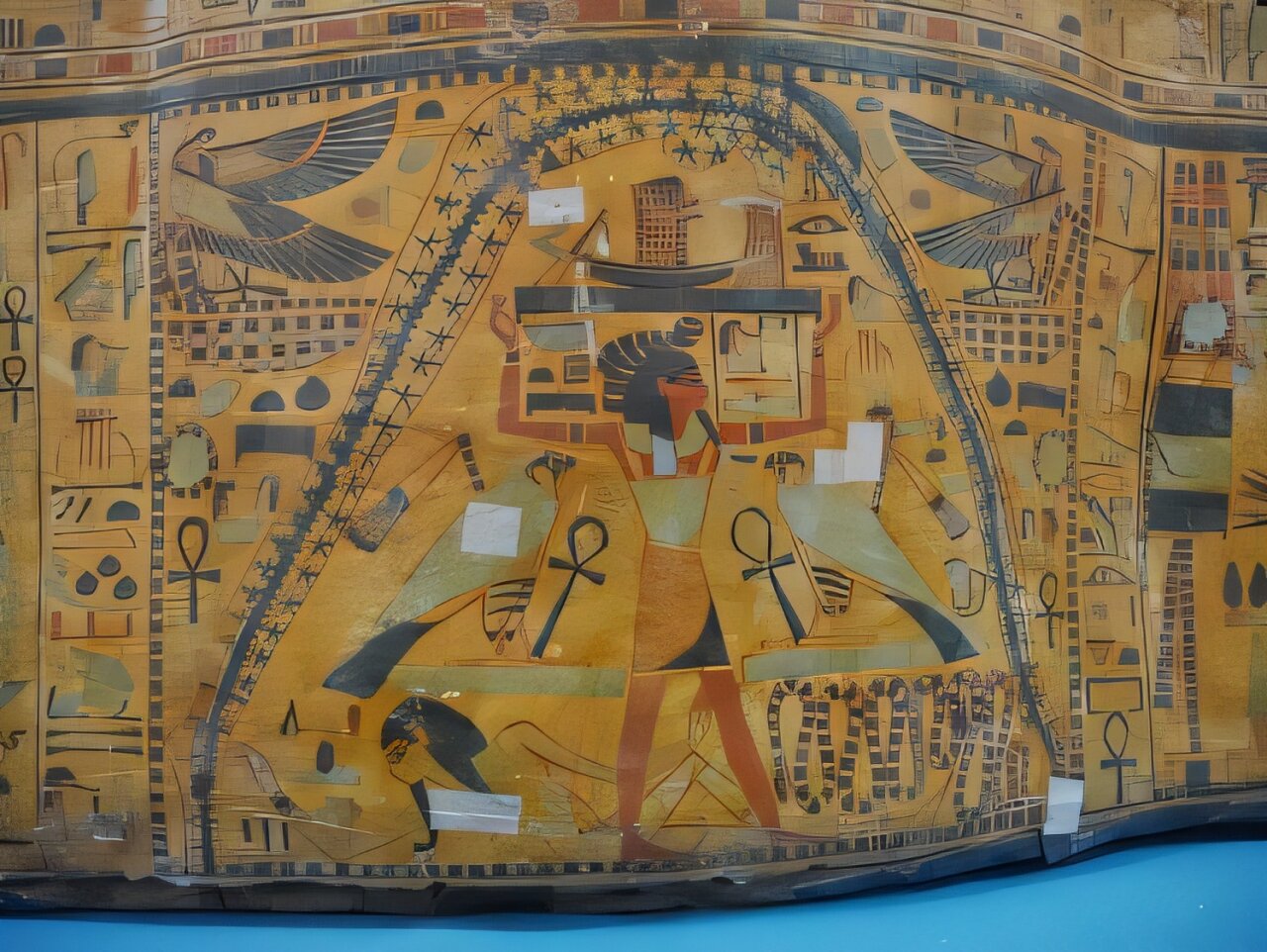

Nut is one of the most iconic and enduring figures in Egyptian mythology. As the goddess of the sky, she is frequently shown as an enormous, nude woman, her body arched gracefully from horizon to horizon, her feet and hands touching the earth. Her limbs form the vault of heaven, separating the chaos of the universe from the ordered world below.

In mythology, Nut performed a vital cosmic function: each evening, she swallowed the sun, only to birth it anew every morning. The Milky Way, in this context, may have been seen not as a separate entity, but as part of the celestial tapestry that Nut wove across the sky.

But what if the Milky Way was not just a background detail in this divine portrait—what if it was purposefully, consciously represented in the art?

A Black Curve Through the Stars

Dr. Graur embarked on a meticulous visual and textual analysis, reviewing 125 depictions of Nut across 555 ancient Egyptian coffins, spanning nearly 5,000 years. It was during this sweeping study that he stumbled upon something extraordinary—a deviation from the norm that caught his scientist’s eye.

On the outer coffin of Nesitaudjatakhet, a chantress of Amun-Re who lived about 3,000 years ago, Nut appears as usual—but with a striking addition. An undulating black curve slices through her body, running from her feet to the tips of her fingers. Surrounding it, stars are painted in roughly equal numbers both above and below the line.

This was no ordinary embellishment. To Dr. Graur, the shape was immediately familiar—it resembled the Great Rift, the dark, sinuous band of interstellar dust that divides the bright light of the Milky Way in our night sky.

Comparing this ancient depiction with photographs of the Milky Way, the similarity became stark. “I think the undulating curve represents the Milky Way,” he said. “It could be a representation of the Great Rift—the dark band of dust that cuts through the Milky Way’s bright band of diffused light.”

In other words, the Egyptians may not have just seen the Milky Way; they may have painted it.

The Tombs of Kings and Curves of the Cosmos

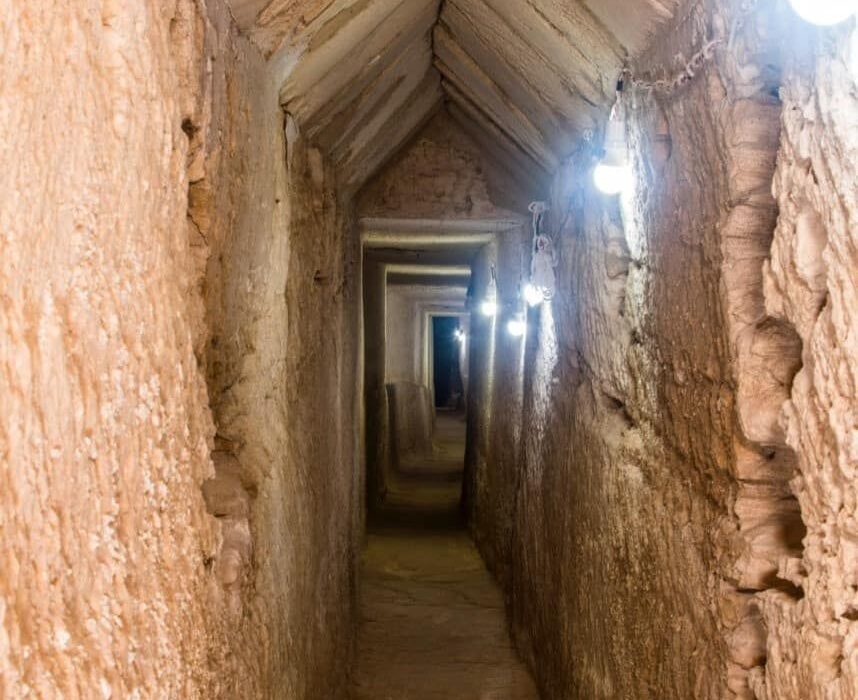

Further support for this interpretation came from the heart of Egypt’s sacred landscape: the Valley of the Kings. In four tombs—among them, the tomb of Ramesses VI—Dr. Graur found similar undulating curves decorating celestial scenes. On the ceiling of Ramesses VI’s burial chamber, two arched Nuits face away from each other, flanking a central divide. Between them, golden, wave-like curves travel from Nut’s head above her back to her lower body, separating the Book of the Day from the Book of the Night.

This imagery, richly symbolic and intensely mathematical in its layout, is not merely decoration. It is cosmography—the rendering of the universe through mythological metaphor. And within it, the Milky Way may have served as both a literal and symbolic boundary, a heavenly river that cuts across the goddess’s form and delineates night from day.

Yet, despite these visual echoes, Dr. Graur urges caution. “Nut is not a representation of the Milky Way,” he asserts. “Instead, the Milky Way, along with the sun and the stars, is one more celestial phenomenon that can decorate Nut’s body in her role as the sky.”

In other words, while Nut contains the Milky Way, she is not limited to it. She is the sky itself—its backdrop and its soul.

Text Meets Sky: The Pyramid Scrolls and Star Maps

Dr. Graur’s latest study builds on his previous work from April 2024, in which he cross-referenced ancient Egyptian texts with astrophysical simulations. Drawing from the Pyramid Texts, Coffin Texts, and the Book of Nut, he examined how Egyptians may have used the position of the Milky Way to frame their cosmological narratives.

The earlier study proposed a seasonal dynamic to the Milky Way’s appearance in the sky. In winter, it was thought to highlight Nut’s outstretched arms. In summer, it traced her spine. This elegant mapping suggests that Nut was not simply an abstract symbol, but one rooted in skywatching, observation, and ritual.

“The texts, on their own, suggested one way to think about the link between Nut and the Milky Way,” Dr. Graur explained. “Analyzing her visual depictions on coffins and tomb murals added a new dimension that, quite literally, painted a different picture.”

Together, these studies present a layered, multidimensional approach to ancient belief: one that wove together poetic mythology, precise astronomical observation, and artistic representation into a single, coherent cosmic vision.

A Galaxy of Meaning

Why does any of this matter in the 21st century, when satellites and supercomputers peer into the birth of galaxies?

Because it reminds us that humanity has always looked upward—not only to chart the stars but to find meaning in them. The ancient Egyptians did not know of spiral galaxies or the physics of dark matter, but they saw in the night sky a reflection of life, death, and rebirth. They saw goddesses in the darkness, and from that darkness, they drew light.

Dr. Graur’s work rekindles this ancient wonder with modern tools. By combining astrophysics with archaeology, he revives lost perspectives and shows us that the boundary between science and myth is more permeable than we think.

“I chanced upon Nut when writing a book on galaxies,” he said. “My interest was piqued after that museum visit with my daughters.” What began as a personal curiosity has become a scholarly journey into the mythologies of the Milky Way across cultures.

More Than Myth

As we continue to probe the universe with telescopes that see into the infrared and radio waves, we are rediscovering the ancients’ cosmic intimacy. The Milky Way—our own spiral arm in the galaxy—was not merely a collection of stars to ancient sky-watchers. It was alive with meaning. And Nut, stretched across the celestial dome, was not just a symbol. She was presence. She was protection. She was the eternal vault under which life unfolded.

Dr. Graur’s findings reintroduce the Milky Way into that sacred dialogue. They do not reduce Nut to a scientific diagram, nor do they inflate science into mysticism. Instead, they do something rarer—they allow the past to speak in the language of the stars and invite the present to listen.

Through Nut’s arched form and the black curves that cross her body, we glimpse an ancient understanding of the heavens that is at once foreign and familiar. The Egyptians, in their own way, mapped the galaxy—not with telescopes, but with myth.

Looking Forward, Looking Up

The Milky Way continues to inspire questions. How did ancient cultures see it? What stories did they tell about it? How did its shifting position through the seasons shape rituals, calendars, and worldviews?

For Dr. Or Graur, these questions are just the beginning. His project to catalog the multicultural mythology of the Milky Way is ongoing. Each discovery adds another thread to a global tapestry of star-lore, woven over millennia by poets, priests, and now, physicists.

In the end, the story of Nut and the Milky Way is a reminder that science and mythology are not enemies. They are twin lenses through which humans have tried to understand the same mystery: the sky above, and our place beneath it.

Reference: Or Graur, The Ancient Egyptian Cosmological Vignette: First Visual Evidence of The Milky Way and Trends in Coffin Depictions of The Sky Goddess Nut, Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage (2025). www.sciengine.com/doi/10.3724/ … .140-2807.2025.01.06