In a groundbreaking discovery that strikes a resonant chord through time, archaeologists have unearthed a pair of copper alloy cymbals from Bronze Age Oman—offering an extraordinary glimpse into a shared musical tradition that once echoed across the Arabian Gulf. These rare instruments not only reveal how music connected ancient cultures but suggest it played a pivotal role in shaping trade, identity, and social life nearly 5,000 years ago.

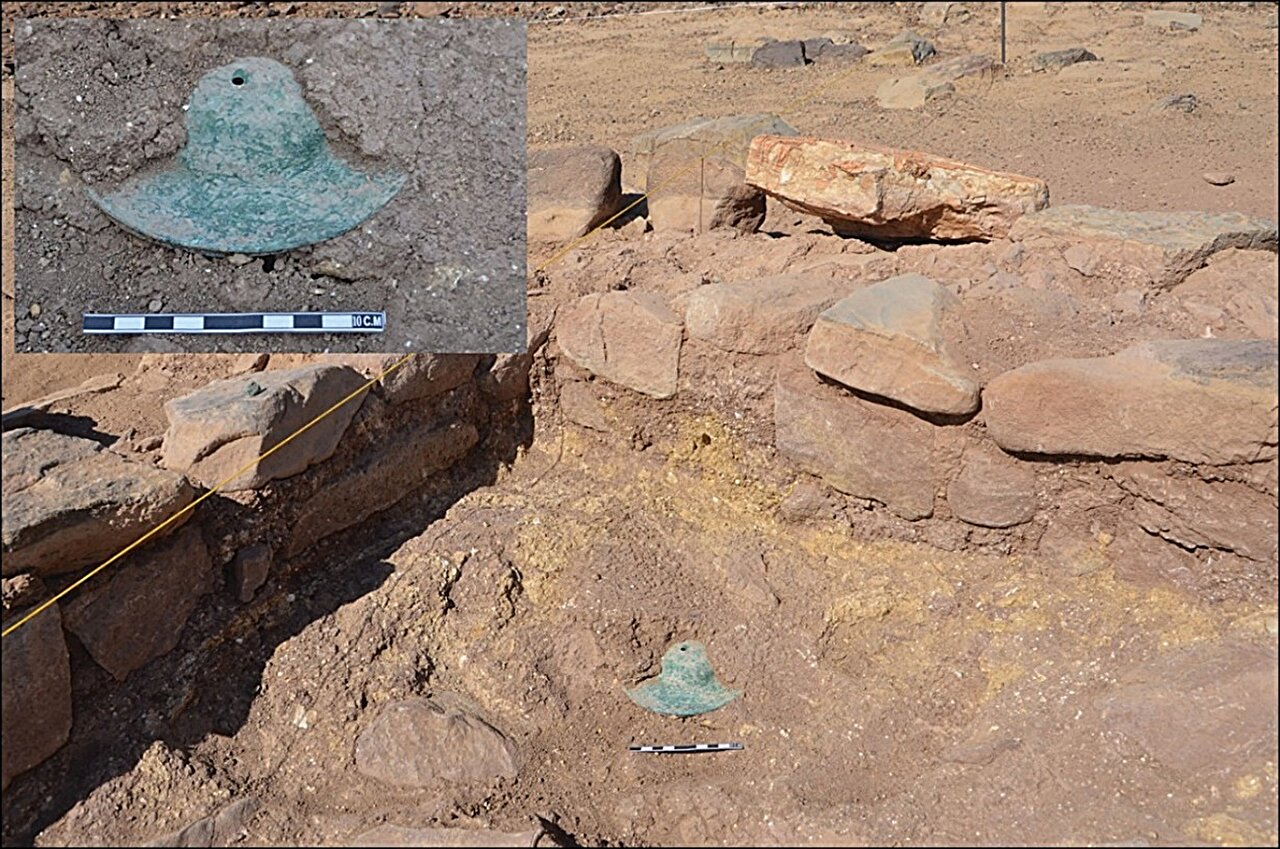

At first glance, the ancient cymbals might seem like simple artifacts, but beneath their corroded surface lies a story of cultural exchange and interregional intimacy. Excavated from the Dahwa site in northern Oman, these cymbals date back to the third millennium BCE and belong to the enigmatic Umm an-Nar culture—a civilization known for its circular tombs, advanced metallurgy, and extensive trading networks.

The Sound of a Forgotten World

Music has long been humanity’s invisible language. It transcends borders, soothes grief, marks celebration, and fosters connection. But tracing its prehistoric past is no simple task. Unlike stone tools or pottery, musical instruments—often made from organic materials like wood or skin—rarely survive the test of time.

That’s what makes the Dahwa cymbals so exceptional. “These copper alloy cymbals are the first of their kind to have been found in good archaeological contexts in Oman,” says Professor Khaled Douglas of Sultan Qaboos University, lead author of the study published in the journal Antiquity. “And they come from a particularly early period that challenges existing theories on the origin and diffusion of such instruments.”

Measuring just a few inches in diameter, the cymbals were likely used in ceremonial or communal settings—perhaps played by dancers or religious figures in rhythmic rituals that synchronized communities and strengthened social bonds.

A Tale Told by Metal

To better understand the instruments’ origin, the research team conducted both visual and isotopic analyses of the copper. While their stylistic resemblance to instruments found in the Indus Valley might suggest they were imported, the chemical signatures of the metal reveal a different story.

“The copper used in the Dahwa cymbals is local,” explains Douglas. “This suggests they were produced in Oman but heavily influenced by contact with other civilizations—most notably, the Indus Valley.”

This fusion of local material and foreign style provides compelling evidence for cultural exchange beyond mere trade. It hints at something deeper: a shared language of music and ritual that spanned oceans and deserts.

More Than Markets: Music as Cultural Currency

For decades, scholars have focused on the economic aspects of Bronze Age trade. Ceramics, beads, and metal objects from across the Arabian Gulf show clear stylistic and technological parallels with those from the Indus Valley civilization—modern-day Pakistan and northwest India. These objects were often interpreted strictly as commodities moved by merchants and middlemen.

But the cymbals suggest another layer—an interweaving of identities and ideas. “The Early Bronze Age, particularly the Umm an-Nar period, has already shown rich evidence of interregional contact,” says co-author Professor Nasser Al-Jahwari. “But what we’re learning now is that those connections weren’t just economic. They were also cultural, and perhaps even spiritual.”

The presence of musical instruments like these cymbals suggests that the people of the Arabian Gulf and the Indus Valley may have shared more than just goods—they might have shared songs, ceremonies, and worldviews.

Music as a Bridge Between Worlds

How might music have functioned in these ancient societies? While no written records exist from the Umm an-Nar culture, comparisons with contemporary civilizations suggest a wide range of uses: religious rituals, communal dances, healing ceremonies, or even diplomatic gatherings.

The communal act of playing and listening to music could have served as a bridge—binding traders, travelers, and communities through shared experiences. Much like today, music may have provided a powerful social glue, encouraging harmony not just in rhythm, but in relationships.

“Discovery of the Dahwa cymbals encourages the view that already during the late third millennium BC, music, chanting and communal dancing set the tone for mediating contact between various communities in this region for the millennia to follow,” write the authors.

Rewriting the Rhythms of History

This discovery invites a rethinking of Bronze Age society in the Arabian Gulf—not as a collection of isolated trade hubs, but as a vibrant network of interconnected cultures, sharing more than just merchandise. It suggests that music, often seen as ephemeral and intangible, may have been one of the most enduring forms of cultural diplomacy.

As archaeologists continue to explore the region’s sands and ruins, it’s clear that many voices from the past have yet to be heard. But thanks to these copper cymbals—forgotten instruments from a forgotten time—we are now one step closer to understanding the rhythms that once pulsed through ancient Oman and beyond.

In the echoes of metal and the silence of the desert, a song from 5,000 years ago still lingers—an ancient harmony between civilizations that found common ground in music long before the modern world would rediscover their connection.

Reference: Bronze Age cymbals from Dahwa: Indus musical traditions in Oman, Antiquity (2025). doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2025.23