In a society where barrenness could ruin reputations and even marriages, a different kind of story was quietly unfolding in the pulpits and manuscripts of medieval England—one that painted infertility not as a curse, but as a profound sorrow to be met with compassion. While the wider medieval world often viewed a childless woman as cursed by God or punished for hidden sins, the Church, in certain tales at least, offered a gentler interpretation—particularly in the retellings of one of the most revered births in Christian history: that of the Virgin Mary.

At the heart of these narratives are Anne and Joachim, Mary’s long-suffering parents, whose two-decade wait for a child made them outcasts in their community. Yet, rather than blaming them or suggesting they were morally flawed, religious texts emphasized their anguish, their faith, and the eventual divine reward of their perseverance. This subtle but significant shift in tone offered solace to many and has now become a focal point in the research of Professor Catherine Rider of the University of Exeter, a historian who delves deep into the murky crossroads of infertility, religious belief, and social exclusion in the Middle Ages.

Her work suggests that some clergy in late medieval England were far more sympathetic toward infertility than the common public opinion of the time—and their sermons, stories, and saints’ lives helped to quietly reshape how childlessness could be viewed in Christian communities.

A Tale Retold: The Story of Anne and Joachim

The origin story of the Virgin Mary was not officially found in the Bible, but it thrived in the pages of texts like The Golden Legend, a collection of saints’ lives compiled by Jacobus de Voragine in the 13th century that became a medieval bestseller. In this sweeping compilation, we meet Joachim—a righteous man who is publicly humiliated at the Temple in Jerusalem for not having fathered a child. Cast aside by religious authorities and shamed in the eyes of his peers, he retreats into the wilderness, not unlike a biblical Job cast into mourning.

Yet what follows is not punishment, but grace. An angel appears to Joachim, telling him that his and Anne’s prayers have been heard and that they will be granted a child—Mary—whose life will change the course of humanity. The message here is quietly radical for its time: infertility is not always the result of sin or divine judgment. It may instead be part of a divine plan—one that leads to miraculous, even redemptive, outcomes.

This narrative did more than explain the holy origins of Mary. It modeled a way for believers—particularly those struggling with infertility—to see their pain as heard, validated, and potentially honored by God. And in a world where childlessness could bring disgrace, this shift in framing was nothing short of revolutionary.

Professor Rider’s Research: Manuscripts, Sermons, and Silent Suffering

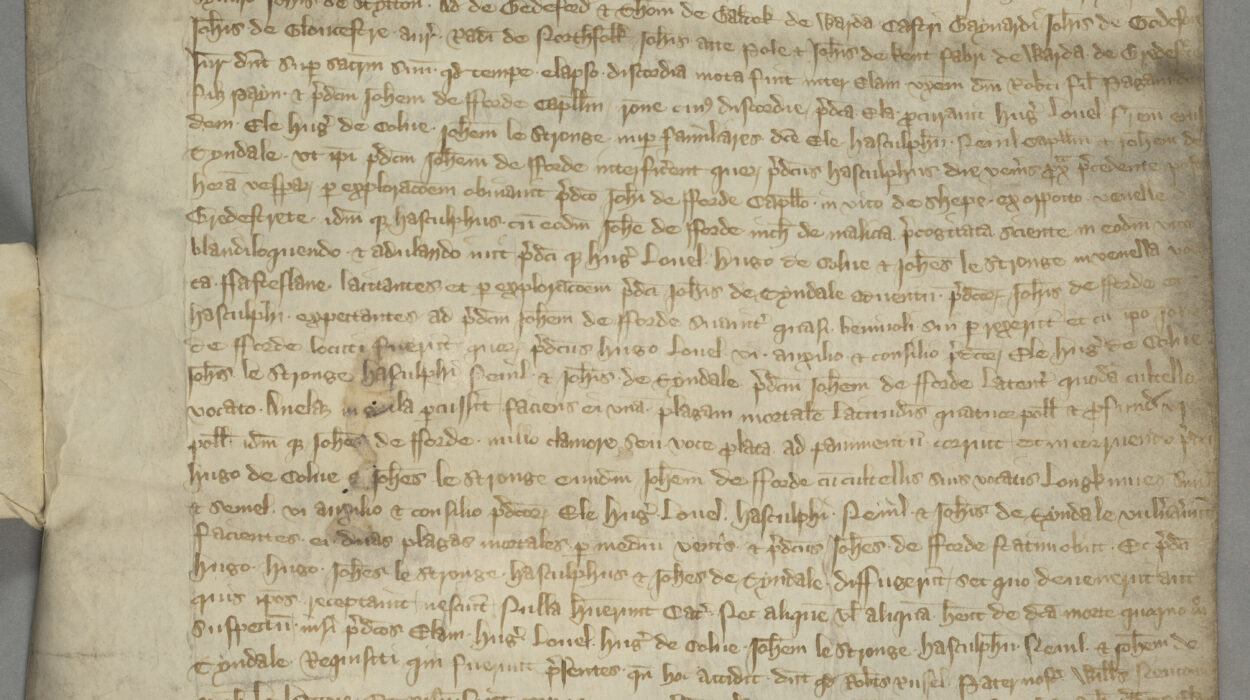

In her new study, Infertility and the Margins of Society: Medieval Churchmen Think About Reproductive Disorders, published in Studies in Church History, Professor Rider explores these themes with fresh eyes. Her work combines textual analysis of medieval religious manuscripts with broader social context, revealing just how different the Church’s messaging could be when it came to childlessness.

Rider’s journey through the British Library and Cambridge University Library unearthed not only original copies of The Golden Legend, but also lesser-known but equally telling texts like Festial by John Mirk, and The Life of St Anne by Osbern Bokenham. Written in the vernacular, these stories were not dry theological treatises meant only for scholars or monks—they were sermons and tales meant for everyday people. They were meant to be read aloud from pulpits, or perhaps shared privately among couples who needed to hear that their suffering was not shameful.

Crucially, Rider notes that in these texts, infertility was often portrayed not just as a woman’s problem—a perspective dominant in both ancient and medieval medical theory—but also something that men experienced deeply, if differently. Joachim’s isolation and shame in The Golden Legend gave space to male grief, something that modern audiences might not expect in a medieval religious tale.

“The Golden Legend reminds us that marginalization is a separate issue from causation or treatment,” says Rider. “Men might not be seen as the cause of a couple’s infertility so often, but they experienced its effects nonetheless.”

Fertility in the Wake of the Plague

These compassionate portrayals gained new significance in the aftermath of the Black Death, which ravaged Europe in the mid-14th century and caused a demographic catastrophe. With populations decimated and family lines at risk of dying out entirely, the societal pressure to reproduce intensified. People turned to religion not just for spiritual reassurance, but for explanations—and hope.

The fact that religious stories still empathized with the infertile, rather than condemning them, is notable in this context. Infertility could have easily been framed as another divine punishment in a time full of such rhetoric. Instead, the retelling of Anne and Joachim’s story became, in Rider’s view, a way for the Church to offer not just theology but emotional refuge.

Moreover, the personal nature of these stories deepened in texts like The Life of St Anne, which was written specifically for a couple—John and Katherine Denston—who were reportedly struggling to conceive. In such instances, literature became more than devotion; it became pastoral care in poetic form. The medieval clergy, through storytelling, were ministering to the most private griefs of their flock.

Changing Emphases, Different Audiences

Interestingly, each manuscript Rider studied tailored its depiction of Anne and Joachim’s experience slightly differently—reflecting the audience it served. In Festial, for instance, the priest who shames Joachim is criticized more heavily, perhaps to underscore that the church ought to be a place of compassion, not condemnation.

These narrative tweaks—subtle yet powerful—demonstrate that medieval religious authors were not operating in a vacuum. They responded to their communities, understood the emotional lives of their congregations, and offered stories that not only reinforced doctrine but also soothed pain. Whether from pulpit or page, these stories offered a narrative that allowed believers to hold both sorrow and faith without contradiction.

From Margins to Meaning: A Medieval Reimagining of Infertility

Ultimately, Professor Rider’s research reframes how we understand medieval attitudes toward infertility. Rather than blanket condemnation, there was nuance—especially within the Church. Religious literature, rather than shunning the infertile, often centered them. Anne and Joachim became more than just the parents of Mary; they became archetypes of faithful suffering, whose redemption lay not in what they lacked, but in what their faith made possible.

And this shift mattered. In a time when childlessness could mean social death, being reminded that even the grandparents of Christ had known this pain—and had been honored, not forgotten—was a balm to many. These were stories that whispered hope into silent despair, that welcomed the marginalized back into the heart of faith.

So while modern science has changed the way we understand infertility, there’s still something profoundly moving about these ancient stories. They remind us that long before fertility clinics and hormone therapies, people turned to story, to scripture, and to faith to make sense of their longing—and that sometimes, those stories gave them not just answers, but comfort.

And in that, the medieval Church may have been far more progressive than we imagine.

Reference: Catherine Rider, Infertility and the Margins of Society: Medieval Churchmen think about Reproductive Disorders, Studies in Church History (2025). DOI: 10.1017/stc.2024.37