In the vast, sun-scorched deserts of southern Arabia lies a hidden tapestry of ancient memory—etched not in parchment, but in stone. Across Oman’s Dhofar region, over 7,000 years of human ingenuity, survival, and symbolism are written in the weathered remnants of monumental structures. A new study published in PLOS One on May 28, 2025, uncovers the rich history embedded in these ancient stones, revealing how early pastoralists adapted their monument-building practices in response to dramatic shifts in climate and culture.

Led by Professor Joy McCorriston of The Ohio State University, a team of international archaeologists examined 371 archaeological monuments, uncovering patterns that show how humans, scattered by an increasingly arid environment, nonetheless found ways to stay connected—physically, socially, and spiritually. These monuments, humble or grand, were not static tombs or relics of forgotten rituals. They were living technologies of communication, social cohesion, and environmental adaptation.

Echoes of a Greener Past: Monumental Beginnings in a Humid South Arabia

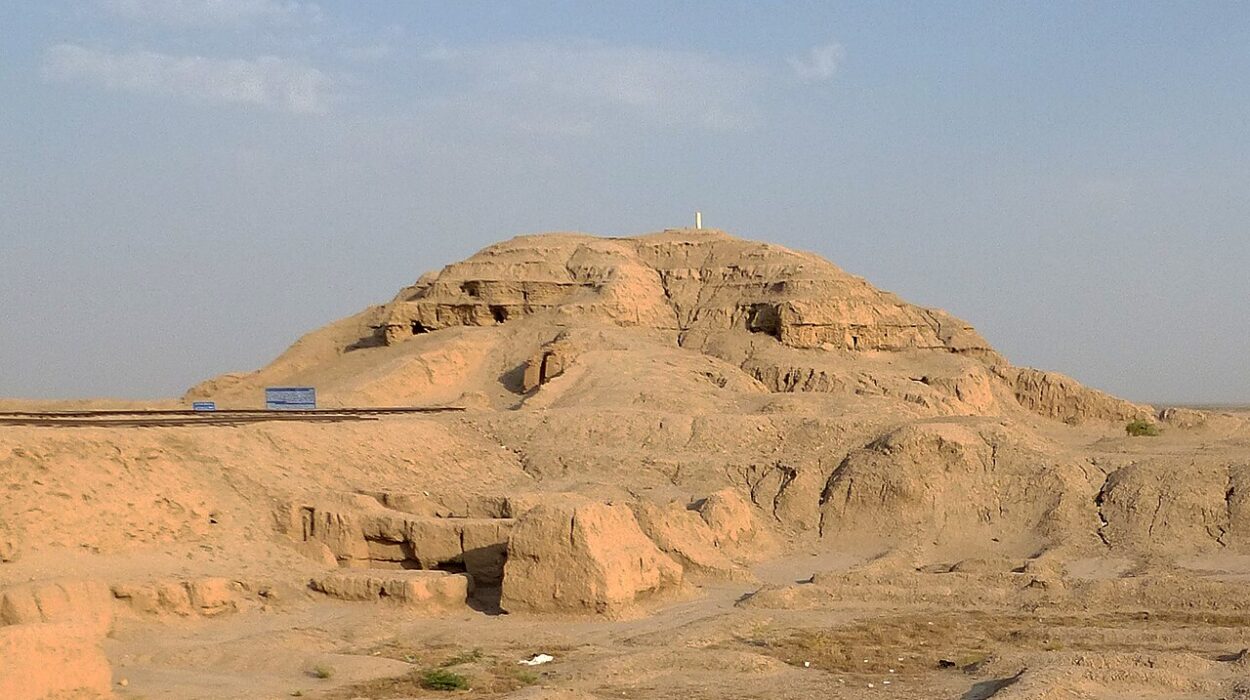

Our story begins in a South Arabia that is scarcely recognizable today. Between 7500 and 6200 years Before Present (BP), the Dhofar region was lush with vegetation, sustained by rains that far exceeded the parched climate of modern times. This Holocene Humid Period provided abundant grazing grounds and fresh water, allowing groups of early Neolithic pastoralists to live in relatively large, stable communities. These groups could afford the time and collective effort required to erect massive stone monuments.

The largest of these early structures were Neolithic platforms—broad, heavy, and often constructed from stones so massive that moving them would have required at least seven strong individuals working in concert. These weren’t haphazard piles of rock. They were feats of engineering, intentional expressions of a shared identity and purpose. The size and sophistication of these monuments suggest that early pastoral societies valued communal effort and collective presence.

Some of these early constructions likely served as central sites for gathering. Picture dozens of families arriving with their herds, exchanging news, performing animal sacrifices, and feasting under the stars. These gatherings were more than practical events—they were vital reaffirmations of cultural identity and social bonds.

But the rains would not last.

Drying Skies and Shifting Stones: The Rise of Small Group Monument-Building

As the Holocene Humid Period ended, the skies dried and the earth cracked. The lush pastures of southern Arabia gave way to barren expanses, forcing once-cohesive communities to scatter in search of water and grazing lands. This slow but unrelenting process of aridification changed everything—not just how people lived, but how they remembered, how they connected, and how they expressed meaning.

The ancient monumental traditions did not vanish with the water. They adapted.

With large-scale group collaboration no longer feasible, monument-building took on new forms. Smaller groups still marked their presence on the landscape, but now the monuments were built in stages, over time, often with fewer hands and lighter stones. These were not grand feats of engineering. Instead, they were quiet acts of perseverance, constructed by those moving from one place to another, adding their stones as markers of memory and connection.

These later structures—known as accretive monuments—are characterized by their layered construction. Unlike earlier platforms erected in a single episode, accretive monuments evolved with time, much like the societies that built them. Among the most intriguing are accretive triliths, composed of three stones arranged in a specific configuration, repeatedly replicated by different groups over generations.

These structures served as more than physical markers. They were emotional and cultural anchors—touchstones of belonging in a world where physical proximity was no longer guaranteed. As Professor McCorriston puts it, “They were building a memory.”

Monuments as Social Technology: Meaning in the Face of Uncertainty

In today’s digital world, communication is instantaneous. But in ancient Arabia, messages were embedded in stone—messages not of words, but of presence, participation, and shared ritual. What exactly these messages conveyed remains elusive, but they were clearly legible to those within the cultural framework. Their purpose extended far beyond commemoration. They were tools of resilience.

As environmental conditions worsened and life became more precarious, pastoralists needed to rely on vast, dispersed social networks. Information about where to find water, which grazing lands were depleted, or where seasonal rains had fallen could mean the difference between survival and death. In such a context, monuments may have acted as silent signal posts, accessible to those who shared cultural knowledge.

“They had to know—did it rain here last year? Did the goats eat all the grass?” McCorriston explained. These monuments may have embodied unspoken contracts, messages to kin and strangers alike: “We were here. We survived. Here’s what we found.”

Moreover, these structures were crucial in maintaining the broader social fabric. Isolation in a desert environment wasn’t just physically challenging—it was socially dangerous. Pastoralists needed access to trade goods like seashells, carnelian, agate, and metal. They required marriage partners and allies. The continuity of social ties ensured access to these resources. And so, monuments became a means to reinforce social memory—markers of who belonged to whom, and where alliances lay.

A Global Model of Monumental Memory

The significance of this study extends far beyond the Arabian Peninsula. What McCorriston and her team have created is not just a regional narrative—it’s a framework that could reshape how we understand monumental architecture across the ancient world.

By applying a standardized set of observational criteria across a large number of archaeological sites, the researchers built a model that could be used to analyze the evolution of monuments in other regions facing environmental stress, such as the Sahara, the Mongolian steppes, or the high Andes.

In all these regions, societies have grappled with environmental unpredictability, and in many cases, they too turned to stone to anchor their identities in a shifting world.

This holistic approach marks a major departure from previous research, which often focused on specific sites in isolation. By treating these ancient monuments as parts of a broader cultural ecosystem, the researchers could trace the evolutionary threads linking early large-scale construction to later, more fragmented but no less meaningful building practices.

Enduring Stones, Enduring Spirit

This is a story not just of stones, but of spirit. In the weathered remains of platforms and triliths, we glimpse the resilience of human societies—how they responded to environmental upheaval not by abandoning tradition, but by transforming it. Even as pastoralists dispersed across a growing desert, they carried with them the idea of monumentality, repurposed to fit a new reality.

In this sense, the stones speak not just of the past, but of the human capacity to adapt without losing our sense of connection. These ancient pastoralists of Dhofar didn’t simply endure climate change. They reshaped their culture, their rituals, and their ways of remembering to ensure continuity across generations.

Today, as modern societies face climate uncertainty of our own, there is something deeply poignant—and deeply relevant—about these enduring stones. They remind us that resilience is not just about technology or innovation. Sometimes, it’s about finding ways to stay connected, even when the world around us is falling apart.

And perhaps, in that sense, the message of the monuments still echoes across the desert winds—not as a warning, but as a whisper of hope.

Reference: South Arabia’s prehistoric monument landscape shows social resilience to climate change, PLOS One (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0323544