In the quiet forests of Belize, the ruins of Dos Hombres whisper stories long buried under soil, time, and assumptions. For decades, archaeologists have interpreted Maya secondary burials—carefully deposited skulls, teeth, or long bones found in later graves—as unmistakable signs of violent ritual sacrifice. After all, blood rituals and offerings are well-documented in Mesoamerican cultures. But what if this interpretation misses something profound? What if these remains weren’t just remnants of violence, but tangible threads in a tapestry of memory, belonging, and soul?

A groundbreaking new study by Dr. Angelina Locker, recently published in the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, invites us to rethink what these bones meant to the people who buried them. Using a bioarchaeological lens and focusing on a non-elite burial from the Late Preclassic Maya period (300 BCE–250 CE), Dr. Locker’s research challenges traditional assumptions, suggesting that secondary burials may have held deep spiritual and ancestral significance beyond sacrificial violence.

The Layers Beneath Maya Burials

In ancient Maya society, burials were not merely acts of disposal. They were statements—about identity, memory, kinship, and place. Yet, when archaeologists unearth skulls or bones deliberately placed in burials that are not their original resting places, these remains are often immediately labeled as victims of sacrificial rites. This narrative, while partially supported by historical sources, paints only a portion of the full picture.

Secondary burials—where parts of human bodies like mandibles, teeth, or arm bones are carefully reinterred—were common in the ancient Maya world. But as Dr. Locker points out, interpreting them solely through the lens of violence overlooks alternative explanations rooted in the Maya’s intricate cosmology.

A Soul Divided: Maya Beliefs About the Afterlife

To truly understand Maya burial practices, one must begin with their conception of the soul, or more accurately, souls. Unlike Western traditions that often view the soul as a singular entity, the Maya believed it could be divided into multiple components, each residing in different parts of the body and having its own spiritual function.

The Baah, representing the self and associated with the head, was seen as the vessel of one’s identity and life force. Ik’, or breath-soul, was linked to wind, jade, and especially the teeth—objects that were believed to retain spiritual breath even after death. The Ch’ulel, the spiritual essence, lived in the heart and blood, tying emotion and vitality to physical life. Lastly, the Wahy were spirit companions—often animals—that were connected to a person and would die or vanish upon their human counterpart’s death.

This conceptual framework allowed for the soul to be fragmented and re-embodied in different ways. A skull or a tooth was not just a leftover of a body—it could still “speak,” embodying the essence of a person and maintaining a spiritual link with the living. Thus, moving or burying a tooth with a descendant wasn’t desecration—it was communion.

Beyond Sacrifice: The Case of the Dancer Group Burial

At the heart of Dr. Locker’s study is a particular burial uncovered on the outskirts of Dos Hombres, a once-bustling Maya city with a population of up to 15,000. The site had yielded relatively few burials—only 21 graves and the remains of 35 individuals—but one household, dubbed the “Dancer Group,” held a mystery that would help rewrite the narrative of Maya funerary practices.

Roughly 1.55 kilometers west of the urban center, the Dancer Group represented a rural, commoner household. Within this modest setting, three bundled burials were discovered, but Locker’s focus was on one: Burial Episode 2. While initial interpretations classified it as a sacrificial primary burial—with the remains of additional individuals placed alongside a young woman—Dr. Locker proposed a more nuanced view, rooted in biological analysis and cultural context.

The primary skeleton was that of a young woman, accompanied by mussel shell remnants, a marker stone, and the dental remains of two other individuals: one aged 20–34, and the other 30–40 years. The unusual inclusion of only teeth—rather than full skeletons—raised questions. Traditional thinking might interpret them as sacrificial offerings. But Locker turned to science to probe deeper.

Tracing Origins in the Teeth: Isotope Analysis

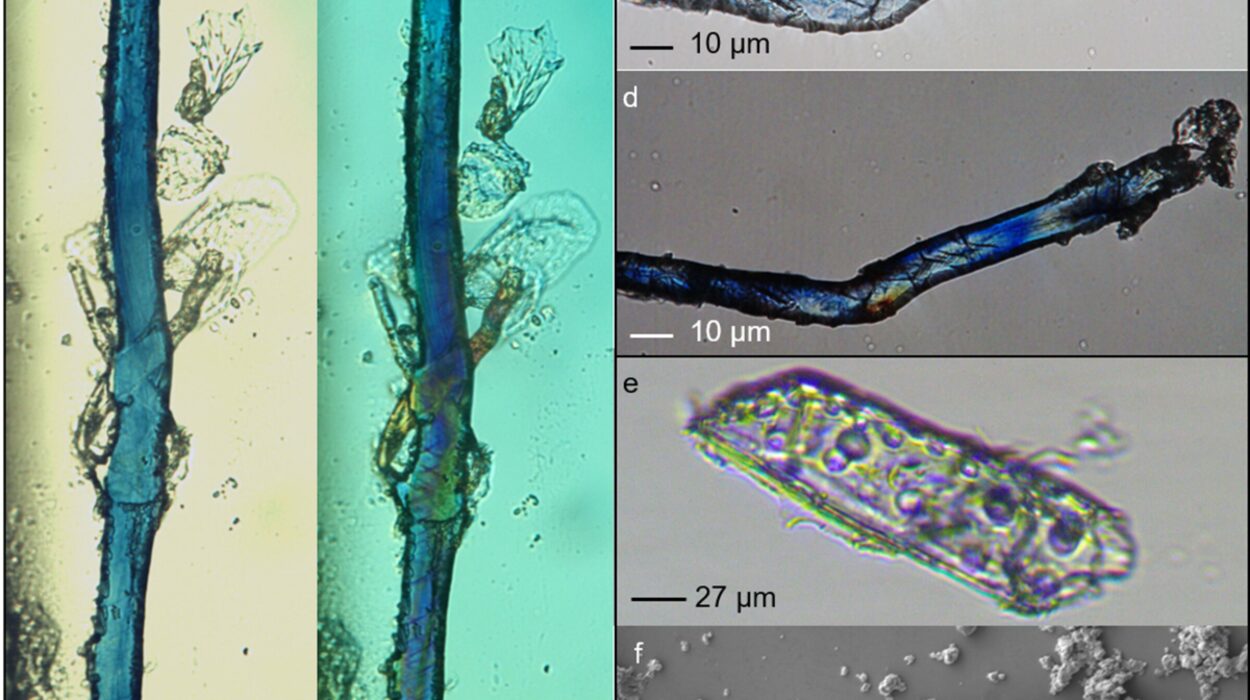

Bioarchaeology offers a powerful toolkit for investigating ancient lives. One such tool is isotope analysis, which examines the chemical composition of human remains to reveal clues about diet, geography, and movement. In this case, strontium and oxygen isotopes—elements absorbed from water and food during childhood and stored in teeth—provided critical data.

The results were compelling. While the young woman was native to Dos Hombres, the two individuals represented by the teeth were not. They had grown up elsewhere, in a different geological region, and their remains had been brought to this grave later. This discovery undermines the idea that they were sacrificial victims, interred at the time of the young woman’s death. Instead, it suggests deliberate placement of ancestral remains into her grave—a symbolic act, not a violent one.

Burial as Belonging: Ancestry and Placemaking

So why place ancestral teeth in a young woman’s grave? The answer may lie in how the ancient Maya viewed ancestry, land, and belonging. Burial wasn’t only about the dead—it was about the living and their relationship to the past. In a society where lineage, origin, and connection to land were vital, bringing ancestral remains to a burial site may have helped legitimize claims to territory or reestablish ties with distant kin.

This act of bringing non-local ancestors to a new burial ground reflects an intentional effort to anchor identity in place. It may have been a way of stating, “We belong here. Our ancestors are with us.” In this sense, the burial of the young woman with ancestral teeth wasn’t a ritual of sacrifice but a ritual of continuity. Her grave became a sacred node of connection—a portal between past and present, blood and land.

Rethinking the Role of Commoners in Maya Mortuary Rituals

Another important facet of Dr. Locker’s study is the socio-economic status of the individuals involved. Much of Maya mortuary analysis has focused on elite tombs, laden with jade, ceramics, and monumental architecture. But here, the burial was peripheral and non-elite—far from ceremonial centers and lacking grand offerings.

This context is critical. Sacrificial rites, especially involving human remains, were often associated with elite displays of power, religious dedication, or architectural consecration. The idea that a rural, commoner burial would be the site of such ritual violence strains credibility. Instead, it makes much more sense to interpret the inclusion of secondary remains as acts of reverence, remembrance, and ancestral engagement—practices not reserved for the powerful, but woven into everyday life.

Reimagining the Dead: New Narratives, Old Bones

Dr. Locker’s work is part of a broader trend in archaeology and anthropology—one that pushes back against reductionist, one-size-fits-all interpretations of the past. Just as modern societies are complex, so too were ancient ones. The Maya lived in a world saturated with meaning: where wind and stone, blood and breath, life and death all intersected in sacred ways.

By examining one seemingly ordinary burial, Dr. Locker opens a window into a world where teeth carried souls, graves forged kinship, and bones told stories far richer than violence. Her study challenges us to reconsider what we think we know about ancient death practices and to listen more carefully to what the bones are really saying.

Conclusion: Living with the Dead

The Maya didn’t simply bury their dead and move on. They lived with them—through memory, ritual, and even literal presence in bones and teeth. Dr. Locker’s research reminds us that death, in the Maya world, was not an end but a transformation. The remains we find in graves were not merely leftovers—they were symbols, messengers, and anchors of meaning.

In challenging the default interpretation of secondary burials as sacrifices, this study offers something powerful: a more human story. One where people, even millennia ago, tried to stay connected—to their ancestors, their land, and their identity. And in that effort, they left behind not just remains, but profound echoes of who they were and what they believed.

The bones of the dead may be silent, but thanks to research like Dr. Locker’s, their meaning is anything but.

Reference: Angelina J. Locker, Dearly De-Parted: Ancestors, body partibility, and making place at Dos Hombres, Belize, Journal of Anthropological Archaeology (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.jaa.2025.101681