The Indus Valley Civilization, also known as the Harappan Civilization, flourished between approximately 2600 BCE and 1900 BCE along the fertile floodplains of the Indus River and its tributaries. Stretching across what is now Pakistan and northwestern India, it was one of the great cradles of human civilization, comparable in scale and sophistication to Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt. Yet unlike its contemporaries, the Indus left behind no deciphered written records, and its monuments do not speak in clear voices.

What remains are the ruins of cities—Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, Dholavira, Lothal—and the artifacts buried within them: terracotta figurines, stone seals engraved with mysterious symbols, fire altars, and architectural clues. Through these remnants, scholars attempt to piece together the beliefs, rituals, and spiritual life of a people who remain, in many ways, enigmatic.

The religion of the Indus Valley is not something we can reconstruct with certainty. But archaeology, anthropology, and comparative studies provide a tapestry of interpretations—one that suggests a culture deeply rooted in fertility, nature worship, ritual purity, and possibly the earliest foundations of religious practices that would later evolve into Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism.

To explore the religion and rituals of the Indus Civilization is to peer into a distant mirror, where fragments of faith survive in clay, stone, and urban design, inviting us to wonder about the spiritual imagination of one of humanity’s earliest great cultures.

Urban Sacred Landscapes

The layout of Indus cities itself reveals a spiritual dimension. Harappan urban planning was meticulous: streets laid out in grids, houses equipped with bathing areas, advanced drainage systems, and citadels overlooking lower towns. While these features reflect technological genius, they also hint at religious concerns.

The Great Bath of Mohenjo-daro, for instance, is perhaps the most iconic structure linked to ritual life. This large, watertight pool with brick steps leading down on either side was carefully designed to hold water, with provisions for draining and refilling. Scholars believe it was not a mere public bath but a sacred space for ritual purification. The symbolism of water as a purifier is deeply embedded in South Asian religions even today, suggesting continuity from Harappan times.

Fire altars discovered at sites like Kalibangan and Lothal point to another dimension of ritual practice. These rectangular brick structures, aligned in specific patterns, suggest ceremonies involving offerings to fire. Fire, as a medium of transformation and a bridge between humans and deities, would later become central in Vedic rituals.

The deliberate integration of religious spaces into city planning shows that spirituality was not a separate domain but woven into everyday life and governance. The city itself became a sacred landscape, where religion and civic life converged.

Seals, Symbols, and the Mystery of the Script

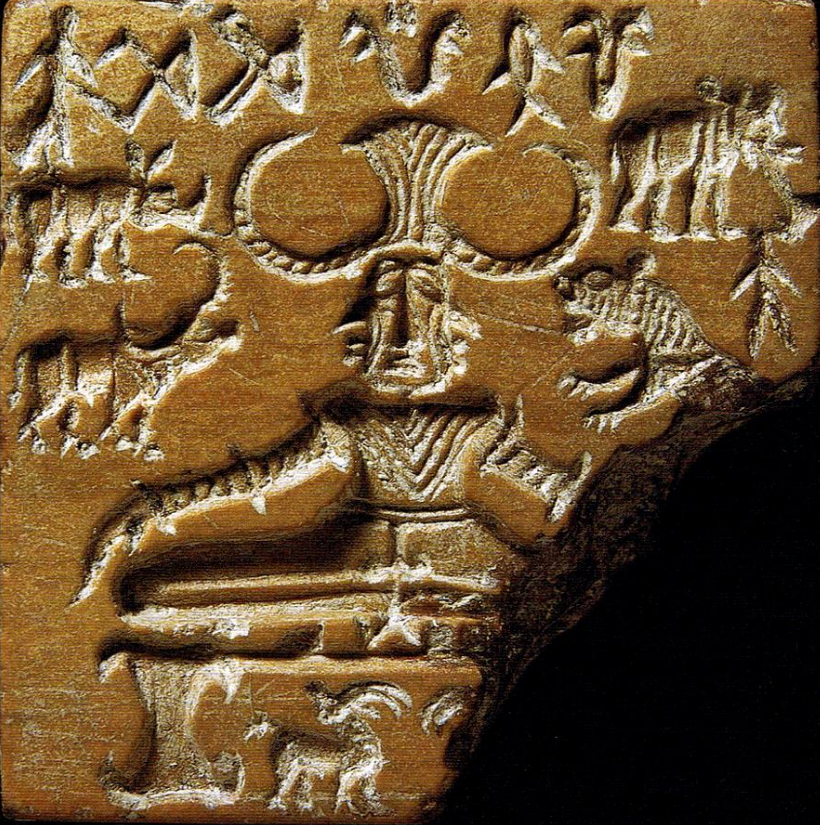

One of the most tantalizing legacies of the Indus Civilization is its thousands of seals—small carved pieces of steatite or other materials, often bearing images of animals, deities, and inscriptions in the still-undeciphered Indus script.

These seals were likely used for trade, identification, and ritual purposes. But their imagery reveals layers of religious symbolism. Among the most famous is the so-called “Pashupati Seal,” depicting a horned, seated figure surrounded by animals, often interpreted as a proto-Shiva or “Lord of Beasts.” The figure sits in a yogic posture, suggesting that meditation and ascetic practices may have roots in Harappan spirituality.

Other seals depict sacred animals—bulls, elephants, tigers, rhinoceroses—and mythical creatures, possibly reflecting totemic worship or the symbolic association of divine power with animal strength. The frequent appearance of the unicorn motif, though likely mythical, suggests a creature of spiritual or ritual importance.

Because the script remains undeciphered, we cannot read their prayers or hymns, but the consistency of symbols across vast distances shows a shared religious vocabulary. These seals may have served as talismans, ritual tokens, or markers of religious affiliation, embedding faith into the fabric of commerce and daily life.

Fertility and Mother Goddess Worship

Terracotta figurines of women with exaggerated hips, breasts, and ornamented bodies are among the most common artifacts from Harappan sites. These have been widely interpreted as representations of a Mother Goddess, symbolizing fertility, abundance, and the generative power of nature.

The worship of a Mother Goddess is one of the oldest religious traditions in human history, found in Neolithic societies across the world. In the Indus context, these figurines may have been placed in households or shrines to invoke blessings of fertility for crops, animals, and families. The presence of male figurines, often associated with animals or horned deities, suggests a complementary worship of male gods linked with power, protection, and procreation.

The agricultural basis of Harappan society likely reinforced fertility cults. Seasonal cycles, harvest rituals, and offerings to ensure rains and prosperity would have been central to religious practice. In this way, the rhythms of the natural world shaped the spiritual imagination of the Indus people.

Animal Symbolism and Sacred Beings

Animals occupied a special place in Indus religious thought. Bulls, in particular, appear frequently on seals and figurines, symbolizing strength, virility, and agricultural wealth. The humped bull may have been revered as a sacred animal, much like the cow is in later Hindu tradition.

Elephants, tigers, and rhinoceroses also appear, perhaps as embodiments of natural forces or guardians of sacred power. The composite creatures on seals, part-animal and part-human, suggest myth-making traditions and a symbolic understanding of the world where boundaries between human and non-human blurred.

Serpents, associated with fertility and regeneration in many cultures, may also have held sacred significance. Later South Asian traditions abound with serpent deities (nagas), and it is possible that their origins trace back to Harappan beliefs.

Through these animals, the Harappans expressed reverence for the natural world, weaving spiritual significance into their ecological surroundings.

Ritual Purity and Daily Life

The emphasis on baths, wells, and advanced sanitation systems suggests that purity was not only practical but also spiritual. Cleanliness may have been a prerequisite for participation in religious ceremonies. The Great Bath likely served as a communal ritual space where initiates purified themselves before rites.

Household shrines and small altars have also been uncovered, suggesting that religious practices were not limited to grand public spaces but permeated domestic life. Offerings of food, terracotta figurines, and small vessels may have been part of daily household rituals to invoke divine protection.

The Harappan emphasis on ritual purity resonates with later South Asian traditions, where water, fire, and cleanliness remain integral to spiritual practice.

Death, Burial, and the Afterlife

The way a civilization treats its dead reveals its beliefs about life, death, and what lies beyond. Indus burials show diversity—ranging from extended inhumations (bodies laid flat in graves) to urn burials with cremated remains. Grave goods such as pottery, ornaments, and tools suggest a belief in some form of afterlife, where possessions might be needed.

Unlike the grand pyramids of Egypt or ziggurats of Mesopotamia, the Indus Civilization did not build monumental tombs. This absence may reflect a society where religious focus was not on kings or elites but on communal and domestic spirituality. Their cemeteries, modest yet intentional, point toward a vision of death integrated into the cycle of life, rather than glorification of individuals.

The lack of emphasis on the afterlife as a central religious theme may also signal a spirituality focused more on the present world—fertility, prosperity, purity, and harmony—than on elaborate notions of the hereafter.

Continuities with Later Traditions

Though the Harappan script remains undeciphered, and much about their religion is speculative, many scholars argue for cultural continuities between the Indus Civilization and later South Asian religious traditions.

The horned, yogic figure on the Pashupati Seal resembles Shiva, one of Hinduism’s principal deities, often associated with asceticism, animals, and fertility. The Great Bath echoes later Hindu practices of ritual bathing in rivers and sacred tanks. The emphasis on fire altars finds continuity in Vedic yajna rituals. The Mother Goddess figurines resonate with later goddess traditions, from Shakti to Durga.

The symbolism of animals, serpents, and fertility deities, as well as the centrality of ritual purity, suggests that the Indus worldview did not vanish but evolved, merging with Indo-Aryan traditions to shape the spiritual landscape of South Asia.

The Enigma of Silence

Yet despite these clues, the Indus religion remains elusive. Without deciphering their script, we cannot hear their hymns, prayers, or myths. Their temples, if they existed, have left little trace. The voices of their priests, shamans, or spiritual leaders are lost to time.

What remains is a silence, filled only by broken terracotta, carved seals, and ruined cities. This silence invites both humility and imagination. It reminds us that religion is not always written in stone or scripture; it can be embedded in daily rituals, in the design of a city, in the reverence for water, animals, and earth.

The mystery of Indus religion challenges us to think of spirituality as something beyond texts—a lived experience, a rhythm of life, a sacred connection to nature and community.

Conclusion: A Sacred Legacy

The Indus Civilization’s religion and rituals cannot be fully reconstructed, but the fragments we hold point toward a society deeply attuned to the cycles of life, fertility, purity, and the sacredness of the natural world. Their spirituality was not about towering monuments or written dogmas but about a subtle weaving of the sacred into daily existence.

From the Great Bath’s waters to the enigmatic seals, from the Mother Goddess figurines to the fire altars, we glimpse a civilization where religion was inseparable from life. Its echoes reverberate across millennia, shaping the cultural and spiritual heritage of South Asia.

In studying the Indus Civilization, we are reminded that religion is not only about gods and temples but about how people make sense of their world—how they honor life, face death, and seek meaning in the cosmos. The Harappans may remain mysterious, but their rituals whisper to us still, across the silence of thousands of years, carrying the timeless human yearning for connection with the sacred.