For centuries, the southern highlands of Bolivia have whispered tales of a long-lost empire. Scattered stones, weather-worn mounds, and fragments of pottery hint at a vanished world that once flourished near the shimmering waters of Lake Titicaca. This was the realm of Tiwanaku, one of South America’s earliest and most enigmatic civilizations—older than the Inca, yet still cloaked in mystery.

Now, a remarkable discovery is helping to peel back the centuries. On a quiet hilltop some 130 miles south of Tiwanaku’s central ruins, archaeologists have unearthed a previously unknown temple complex, hidden for a thousand years beneath soil, grass, and the slow march of time.

Led by researchers from Penn State University and Bolivian institutions, the find—Temple Palaspata—is shaking up assumptions about how far the Tiwanaku civilization reached, how it maintained power, and how religion and trade may have intertwined to hold it all together.

A City in the Mountains, a Civilization in the Shadows

At its height, Tiwanaku was a marvel of engineering and social organization. Between 500 and 1000 CE, it built towering pyramids, carved monoliths, and developed a complex agricultural system that could feed tens of thousands. It stretched across vast parts of the Andes, influencing territories that are now Bolivia, Peru, and Chile.

And yet, Tiwanaku left no written language. Much of what we know has been pieced together from ruins and speculation. When it collapsed mysteriously around 1000 CE, it left behind more questions than answers. By the time the Inca rose to prominence centuries later, Tiwanaku was already a ghost.

“Their society was sophisticated, but it vanished suddenly,” said Dr. José Capriles, associate professor of anthropology at Penn State and the lead author of the study, published in the journal Antiquity. “By the 15th century, when the Inca came, Tiwanaku was already in ruins.”

Hidden in Plain Sight

The newly discovered temple had been hiding in the open. For generations, Indigenous farmers in the region of Caracollo knew the hill by its local name, Palaspata, but no one realized what lay just beneath the surface.

What made the site particularly intriguing to Capriles and his team was its location—not grand or central, but strategically placed. The hill sits at the crossroads of three important ecological and trade zones: the high-altitude Titicaca basin, the llama-herding plains of the Altiplano, and the agricultural valleys of Cochabamba to the east.

“It was a connector,” Capriles explained. “People, goods, and ideas moved through here. That made it an ideal spot to build a temple—not just as a place of worship, but as a center of cooperation and exchange.”

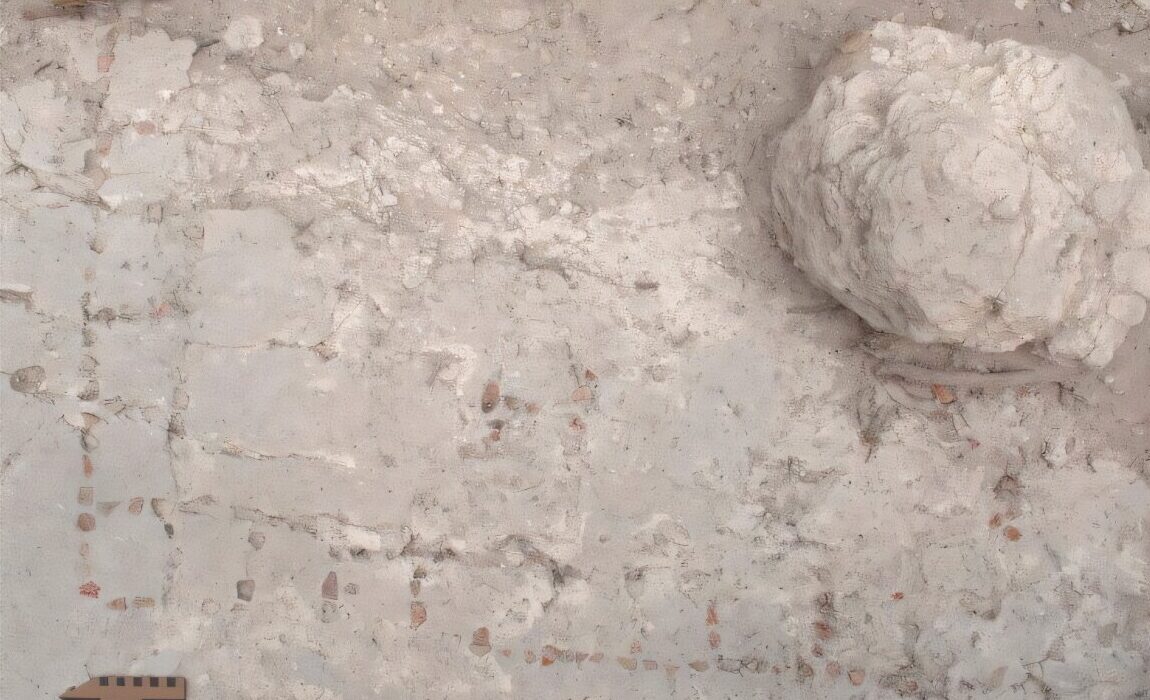

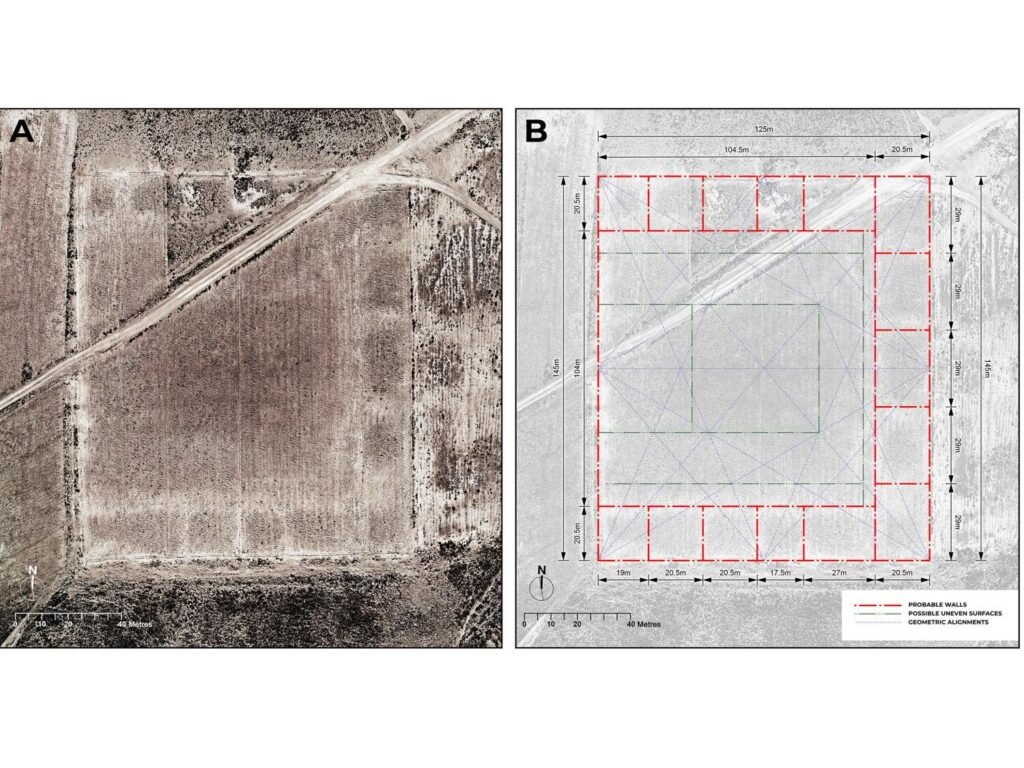

Using satellite imagery and UAV photogrammetry, the researchers created detailed 3D models of the terrain. Beneath a patch of unmapped, quadrangular land, they discovered the clear outlines of an ancient ceremonial complex, measuring about 125 by 145 meters—roughly the size of a modern city block.

A Temple to the Sun—and to Society

The structure, with its 15 quadrangular enclosures surrounding a central courtyard, appears to have been carefully aligned with the solar equinox, when the sun hovers directly above the equator. This alignment suggests that astronomical events played a major role in Tiwanaku rituals, likely tied to agriculture and seasonal cycles.

On the surface of the temple, the team found shards of keru cups, drinking vessels used to consume chicha, a fermented maize beer commonly shared during feasts and festivals. These cups weren’t made with local ingredients—maize doesn’t grow at such high altitudes—but were likely brought in from the warmer valleys far to the east.

That detail speaks volumes. “This wasn’t just a religious site,” Capriles said. “It was a hub of ceremonial exchange, where food, drink, and culture converged. People probably came from distant regions to participate in collective rituals—perhaps to give thanks for harvests, make alliances, or renew political bonds.”

Religion, he added, was the common language that bound different groups together. In the absence of a written script or centralized bureaucracy, spiritual beliefs and shared ceremonies offered a powerful tool for unifying diverse communities.

A Past Rediscovered, a Future Reimagined

The discovery has stirred excitement not only in the scientific world but also among local leaders and residents. Justo Ventura Guarayo, mayor of Caracollo, emphasized the cultural and historical value of the site.

“This is part of our heritage—something that had been completely overlooked,” he said. “We’re working with regional and national officials to protect the site. It’s not just about the past. It’s about identity, tourism, and education for future generations.”

With the guidance of archaeologists, the community is now exploring ways to responsibly open the site to visitors, while preserving its fragile history.

Echoes of a Forgotten Empire

The Tiwanaku civilization remains a riddle, but each new discovery brings its echoes a little closer. The temple at Palaspata offers more than architectural insight—it reveals how ancient societies coordinated across distances, shared sacred traditions, and leveraged religion as social glue.

“It’s a rare chance to witness how people negotiated power and cooperation in landscapes as extreme as the Andes,” Capriles said. “The more we look, the more we find that this civilization was far more complex than we’ve imagined.”

And in many ways, the temple was never truly lost. It waited, watched, and weathered a thousand years until science caught up with memory—until the ruins once dismissed as just another hill revealed a story of connection, belief, and the timeless human need to find meaning in stone and sky.

Reference: José M. Capriles et al, Gateway to the east: the Palaspata temple and the south-eastern expansion of the Tiwanaku state, Antiquity (2025). DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2025.59