Deep beneath the quiet waters of southern Belize’s Punta Ycacos Lagoon lies a secret the sea has kept for over a millennium. Hidden under layers of mangrove peat, archaeologists have uncovered the preserved remains of a complete Late Classic Maya residential compound—a discovery so rare and so perfectly preserved that it is rewriting what we know about Maya life and architecture.

This remarkable find, detailed in a study by Dr. Heather McKillop and Dr. E. Cory Sills and published in Ancient Mesoamerica, brings to light a world once thought invisible—a world of wooden houses, humble labor, and thriving trade networks that sustained one of the greatest civilizations in the Americas.

Discovering Cho-ok Ayin

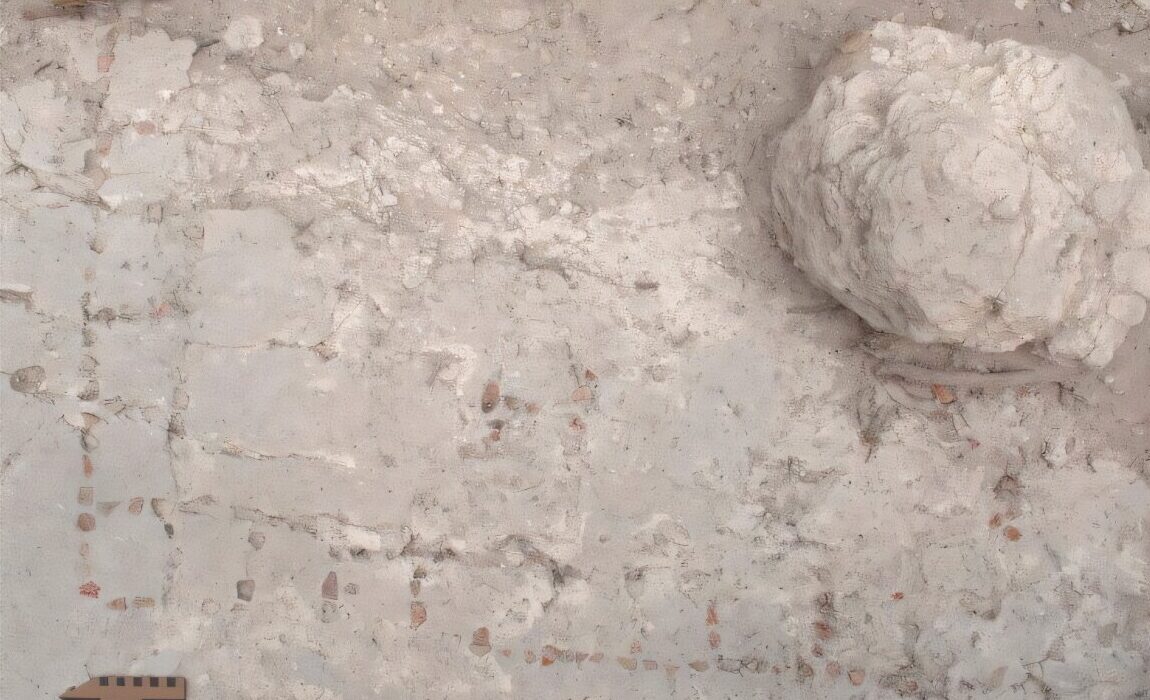

The site, named Cho-ok Ayin, was discovered during a flotation survey in the mangrove lagoons of southern Belize. Measuring roughly 32 by 27 meters, the site was unlike anything previously recorded. Beneath the calm, dark waters, researchers found 56 hardwood posts and three palmetto-palm posts—what remained of ancient Maya buildings, preserved in perfect stillness beneath the sea floor.

The peat in which these wooden structures were buried created an anaerobic environment, meaning one without oxygen. In such conditions, the bacteria responsible for decomposition cannot survive. It was this natural protection that allowed the wooden architecture to endure for over 1,200 years—an extraordinary stroke of luck for modern archaeology.

Dr. McKillop explained that “the preservation of the wooden buildings and wooden objects at the submerged Classic Maya sites in Punta Ycacos Lagoon has not been found elsewhere along the coasts of Belize and the Yucatan.” The mangrove peat, sometimes stretching up to 10 meters below the sea floor, offered a time capsule that nature itself sealed shut.

The Invisible Sites of the Maya

For decades, archaeologists have relied on tools like pedestrian surveys and airborne lidar technology to locate ancient Maya settlements. These methods have revolutionized our understanding of Maya civilization, revealing massive cities, road systems, and agricultural landscapes hidden beneath dense jungles.

But lidar and ground surveys have one major blind spot—they can only detect mounds and stone architecture. Most Maya families, however, lived in pole-and-thatch houses, just like those still seen in rural Maya villages today. These homes, built from perishable materials, rarely survive in the archaeological record. They leave little more than faint impressions in the soil, making them effectively “invisible” to conventional archaeological detection.

Cho-ok Ayin challenges that invisibility. Beneath its mangrove shroud, an entire household compound lay hidden, undetected by lidar or surface surveys. Without this extraordinary preservation, the site—and the people who lived there—would have been completely lost to history.

Life at Cho-ok Ayin

The mapping of Cho-ok Ayin revealed a household compound typical of Maya domestic organization. The site included four main buildings, arranged around an open courtyard.

Building A served as the main residence, where the family likely cooked, slept, and gathered. Buildings B and C appeared to be salt kitchens, while Building D was probably used for salt enrichment. This arrangement indicates that the inhabitants specialized in salt production—a crucial industry in the ancient Maya economy.

Between AD 550 and 800, the Late Classic period, salt was one of the most valuable commodities in Mesoamerica. It was essential for food preservation, animal husbandry, and as a dietary supplement. But more than that, salt was wealth—it was trade, power, and survival.

The Art of Salt Making

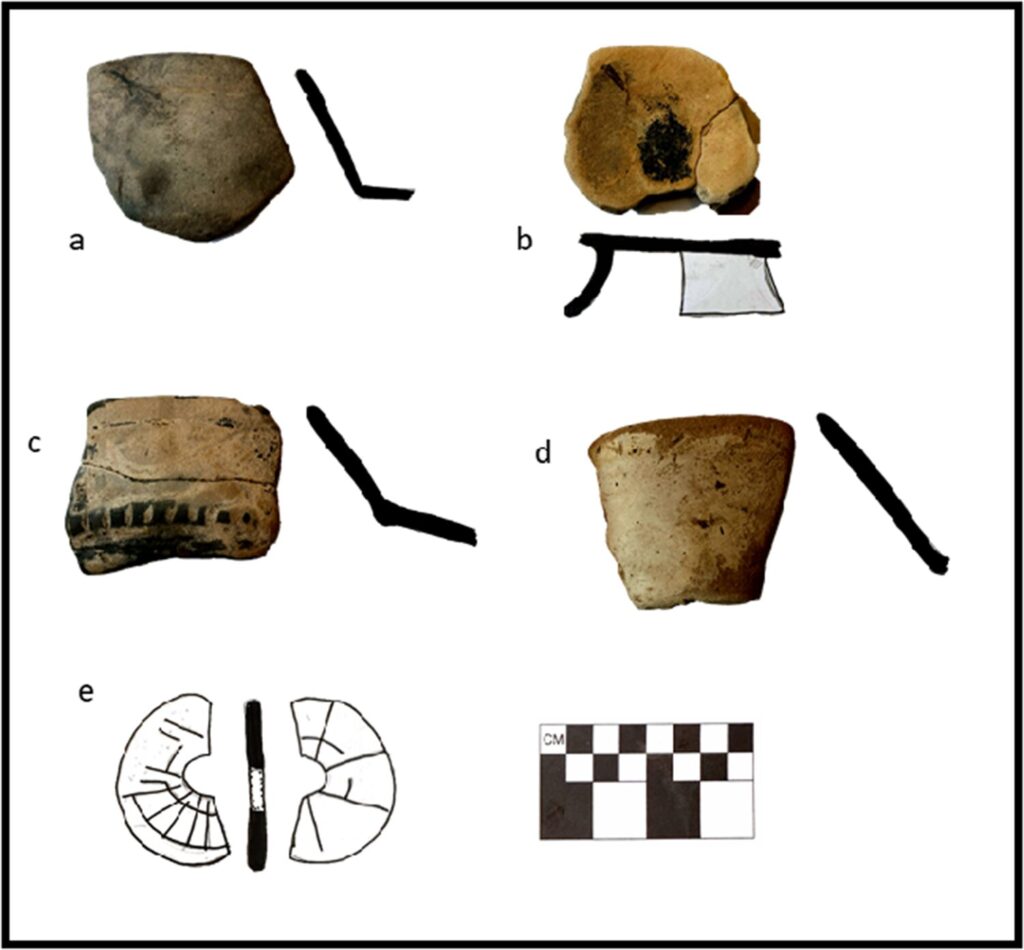

The process of salt production at Cho-ok Ayin was both practical and ingenious. The residents collected saline-rich water from the nearby lagoon, which they then enriched by filtering it through salt-laden sediments held in raised containers. Beneath these, clay funnels directed the concentrated brine into collection pots.

Archaeologists found these clay funnels both inside and outside the buildings, suggesting that brine enrichment was an everyday activity. Once collected, the enriched brine was boiled in large clay vessels over wood fires. As the water evaporated, crystalline salt accumulated at the bottom of the pots.

When the salt hardened, the Maya could either transport it in the same vessels, remove it as salt cakes, or break the pots to free the solidified blocks. The process mirrors modern traditional salt-making practices still observed in Guatemala, where families continue to boil and mold salt much as their ancestors did over a thousand years ago.

The Value of Salt and the Power of Trade

Despite their modest pole-and-thatch homes, the residents of Cho-ok Ayin were far from isolated or poor. Archaeological evidence shows they were connected to a vast regional trade network that spanned hundreds of kilometers.

They had access to Belize Red pottery from the upper Belize River valley, obsidian from highland Guatemala, and finely crafted chert tools from northern Belize. These materials point to both wealth and connection—proof that this small coastal community played an active role in the economic pulse of the Maya world.

Salt, portable and essential, was one of the key goods that tied them into this network. As one of the few coastal producers, Cho-ok Ayin’s inhabitants likely traded their salt for pottery, tools, or even food from inland regions.

Redefining the Maya Landscape

Conventional surveys that rely on mound counting and stone architecture would have completely missed Cho-ok Ayin. To traditional methods, it would have appeared as an empty space—uninhabited, unimportant, forgotten.

But this single discovery, along with others in the nearby Paynes Creek Salt Works, reveals how misleading that invisibility can be. Each of these “invisible sites” represents real lives—families, workers, traders—whose contributions were vital to the functioning of Maya society.

The discovery of Cho-ok Ayin therefore does more than add another dot to the map. It forces scholars to reconsider how they estimate population, measure wealth, and reconstruct daily life in the ancient Maya world. How many other such villages—made of wood, not stone—have vanished without a trace? How many stories remain untold simply because they left no mounds behind?

Preservation Against All Odds

The miracle of Cho-ok Ayin’s preservation lies in the unique conditions of the mangrove peat. Along the southern Belize coast, the combination of sea-level rise and a deep limestone platform created perfect circumstances for anaerobic preservation.

When the sea slowly encroached upon the land, the peat accumulated over time, submerging the once-coastal settlement. The oxygen-free environment halted bacterial activity, effectively freezing the site in time. Wooden posts, usually the first to rot away, remained standing, some still arranged as they were when the buildings stood above the waterline.

Such preservation is almost unheard of in tropical archaeology, where humidity and biological decay usually erase organic materials within decades. In the world of Maya research, this find is as extraordinary as discovering Pompeii beneath the waves.

The People Behind the Posts

Archaeology often focuses on temples and kings, but Cho-ok Ayin shifts the spotlight toward ordinary people—the families who built, worked, and dreamed in the shadows of grand cities. These were salt workers, artisans, and traders who played a vital role in sustaining the great Maya urban centers.

Their world was one of daily labor—hauling brine, tending fires, shaping clay pots. Yet it was also a world of connection and culture, bound to the rhythms of the sea and the demands of trade. Through their efforts, goods flowed inland, feeding the economy of city-states like Lubaantun, Nim Li Punit, and Caracol.

Reimagining the Maya Past

The discovery of Cho-ok Ayin reveals that ancient Maya civilization was not only a society of monumental stone cities but also one of wooden villages, coastal industries, and widespread networks of exchange. It shows that the Maya lived in dynamic environments—jungles, mountains, and coasts—and adapted their architecture and economy to each unique setting.

It also underscores how much we still don’t know. For every temple unearthed or inscription deciphered, there may be dozens of communities like Cho-ok Ayin still hidden beneath the forest, or even the sea.

The Legacy of the Mangrove City

The story of Cho-ok Ayin is ultimately one of resilience—of human ingenuity meeting the challenges of environment and time. The villagers who once walked among those wooden posts never imagined that their homes would one day sleep beneath the ocean. Yet their legacy endures, whispering through the silt and salt, telling us not of kings or conquests but of life itself—honest, laborious, and profoundly human.

Through their discovery, Dr. McKillop and Dr. Sills have given voice to the invisible Maya, illuminating the fragile wooden architecture that once formed the backbone of Maya society. Their work reminds us that history is not written only in stone—it also survives in the quiet breath of the mangrove, in the stillness beneath the waves, and in the enduring trace of hands that shaped salt from the sea.

More information: Heather McKillop et al, Ancient Maya submerged landscapes and invisible architecture at the Ch’ok Ayin residential household group, Belize, Ancient Mesoamerica (2025). DOI: 10.1017/s0956536125000136