On the rugged borderland between Slovenia and Italy, a remarkable secret has been lying silent for thousands of years. The windswept Karst Plateau, known for its dramatic limestone cliffs and deep sinkholes, has now revealed something extraordinary—massive stone megastructures unlike anything previously found in Europe.

Scientists from the University of Ljubljana and the Institute for the Protection of Cultural Heritage of Slovenia have uncovered these enigmatic structures using cutting-edge airborne laser scanning (ALS) technology. What they found beneath the dense vegetation and uneven terrain is rewriting our understanding of prehistoric life.

Stretching up to 3.5 kilometers in length, these vast, low-lying stone walls form funnel-shaped patterns that lead toward hidden pits. Researchers believe they were not defensive fortifications or boundary markers, but sophisticated hunting traps designed to capture large herds of wild animals, such as red deer.

This breathtaking discovery offers a rare glimpse into a forgotten world—one where early Europeans worked together on a scale once thought impossible for their time.

Unveiling Ancient Engineering Through Modern Eyes

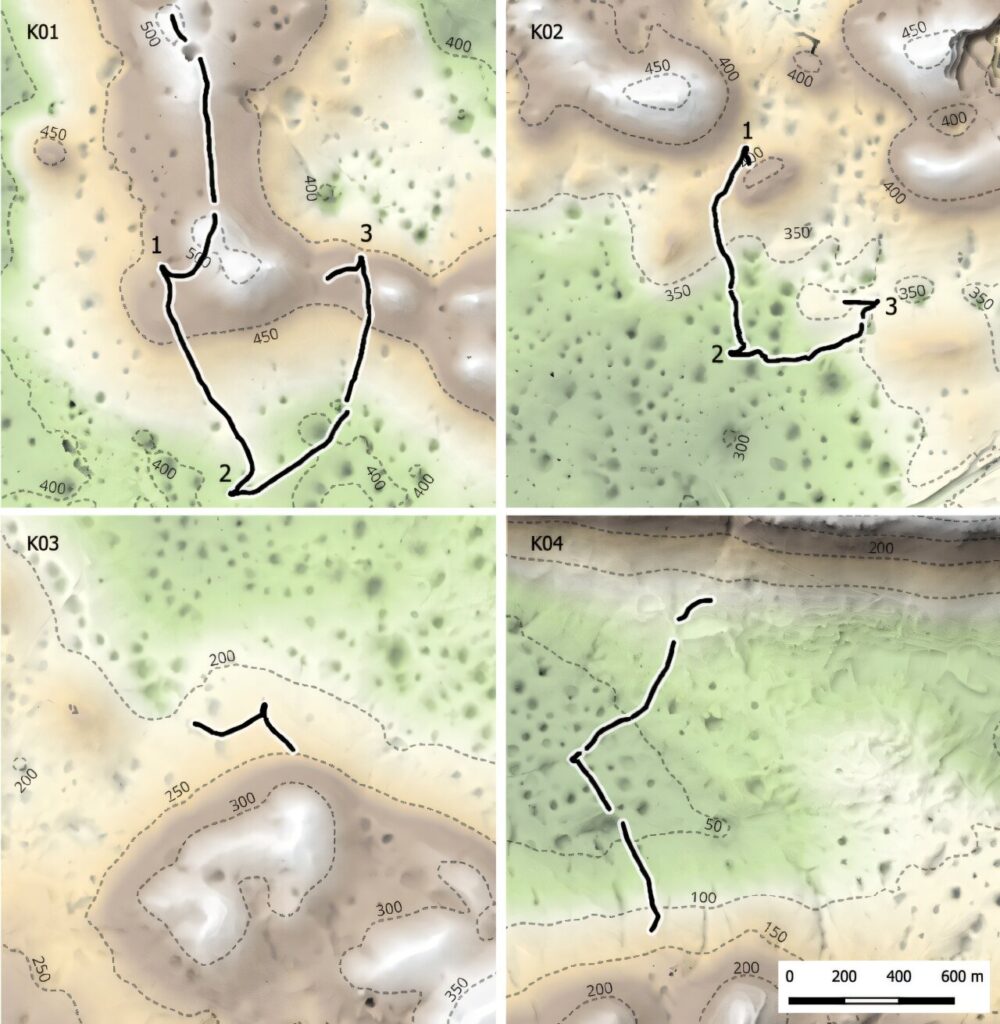

The research team surveyed roughly 870 square kilometers of the Karst Plateau using ALS, a technology that allows scientists to “see” beneath forests and rough landscapes by bouncing laser pulses from aircraft. This high-precision mapping revealed four previously unknown megastructures, each constructed from loosely stacked limestone.

The walls, though now eroded to less than half a meter in height, originally stood less than a meter tall and measured up to 1.5 meters wide. Their preservation is astonishing, their geometry deliberate and purposeful. From above, they appear as giant funnels tapering toward an enclosed pit set beneath a natural cliff—a perfect setup for trapping animals driven along the narrowing walls.

What makes these findings so striking is their resemblance to desert kites—large prehistoric hunting structures found across the deserts of Southwest Asia and North Africa. These kites, dating back over 9,000 years, were used to corral wild animals into confined spaces for mass hunting. Until now, no such large-scale hunting traps had been found in Europe.

The discovery suggests that prehistoric communities on the Karst Plateau were not only resourceful hunters but also capable of extraordinary environmental engineering.

Echoes of a Vanished Hunting Tradition

Radiocarbon dating of material found inside the structures shows they were already abandoned before the Late Bronze Age, meaning they may date back several thousand years earlier. This places their construction somewhere in the deep prehistoric past—long before written records, long before agriculture and metallurgy reshaped European life.

Imagine the scene: vast herds of red deer moving across the stony plateau, guided unknowingly by human-built walls. Dozens, perhaps hundreds, of hunters coordinated in silence, using noise, fire, or movement to drive the animals toward the narrowing funnel. At the final moment, the herd plunged into a pit or over a natural drop where the hunters waited.

These traps reveal not only advanced architectural skill but also profound ecological understanding. The builders clearly knew where animals migrated, how they behaved, and how to harness the terrain to their advantage. This was landscape engineering in its earliest form—a deep fusion of environmental awareness, community cooperation, and survival strategy.

Rethinking Prehistoric Societies

For decades, archaeologists assumed that prehistoric communities in Europe were small, family-based groups with limited capacity for large-scale construction or coordination. But the Karst Plateau megastructures challenge that view dramatically.

According to the research published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), the construction of the largest structure would have required over 5,000 person-hours of labor—far beyond the capability of a single extended family. This means entire communities must have worked together, planning, organizing, and executing complex engineering projects with shared purpose and vision.

As the researchers put it, these installations expose “the coordination of communal labor beyond the domestic sphere, the transformation of landscapes into infrastructural systems, and the coupling of animal ecology with architectural foresight.”

In other words, these were not mere hunters—they were architects of the natural world. They reshaped the landscape to ensure sustenance, and in doing so, laid the groundwork for the social cooperation that would later define human civilization.

A Masterclass in Prehistoric Ingenuity

What makes this discovery even more fascinating is how it reflects an early form of human innovation. These structures demonstrate a kind of problem-solving and foresight rarely attributed to ancient peoples.

To build such extensive traps, the prehistoric inhabitants had to observe animal behavior across seasons, identify migration routes, and design walls that subtly guided entire herds without alarming them. The traps relied not on brute force but on understanding—on the quiet mastery of nature’s patterns.

Each structure’s position appears strategically chosen, taking advantage of natural slopes and cliffs. The limestone walls, though low, would have blended seamlessly into the rocky terrain, becoming nearly invisible until it was too late for the prey.

Such ingenuity speaks volumes about the intelligence and adaptability of these early societies. Their achievements challenge the notion that complex architecture and communal planning began only with agriculture or settled life.

The Karst Plateau: Europe’s Forgotten Frontier

The Karst Plateau itself is a region steeped in mystery. Stretching between the Adriatic coast and the Dinaric Alps, it is a landscape of caves, cliffs, and stony plains—beautiful but unforgiving. For prehistoric people, it was both a challenge and an opportunity.

Its rugged terrain made traditional farming difficult, but it offered abundant wildlife and natural shelter. The limestone bedrock provided material for construction, while its rolling topography created natural traps and vantage points for hunting.

The discovery of these megastructures suggests that far from being primitive wanderers, the people who lived here were strategic and organized. They knew how to harness the land’s features to sustain their communities, long before permanent settlements or metal tools became widespread.

A Window Into a Lost Way of Life

What drives scientists and historians to excitement about these stone traps is not just their engineering—it’s what they reveal about the people who built them. These ancient builders lived in a world where survival depended on cooperation, knowledge, and courage.

Their work reflects an early form of social organization—an understanding that success depended on working together toward a shared goal. The construction of kilometer-long traps would have required planning, leadership, and communication. It would have demanded trust, unity, and collective vision.

In these quiet ruins of stone, we can still hear echoes of the human story—the rise of cooperation, the birth of shared purpose, and the first steps toward civilization itself.

Redefining the Map of Human Innovation

Before this discovery, large-scale animal traps were thought to be unique to desert environments in Asia and Africa. The idea that prehistoric Europeans might have built similar systems was almost unimaginable. Now, archaeologists must reconsider long-held assumptions about cultural exchange and parallel innovation.

Did these European builders independently invent their own version of the desert kite? Or were ideas and techniques shared across continents through ancient networks of migration and communication?

Whatever the answer, the Karst Plateau findings reveal that prehistoric Europe was far more dynamic and interconnected than once believed. The capacity for large-scale planning, engineering, and ecological manipulation was not confined to a few ancient civilizations—it was a shared human trait, rooted deep in our collective past.

Lessons for the Present

These stone walls, humble in height but monumental in significance, remind us that human ingenuity is not bound by time. The same creativity that once guided herds into hidden traps now builds cities, spacecraft, and artificial intelligence. The drive to understand and shape our environment—to cooperate, innovate, and survive—is as ancient as humanity itself.

But there’s another lesson, too. The builders of the Karst Plateau lived in harmony with their surroundings. Their structures were made from local stone, blending seamlessly with the land. They hunted not to dominate but to sustain their communities. In our modern world, where human activity often threatens ecological balance, their example feels especially poignant.

The Stone Memory of Humanity

The discovery of the Karst Plateau megastructures opens a window to a forgotten chapter of human history—a time when intelligence was measured not in words or technology but in the ability to live with the land.

These walls, stretching silently across the hills of Slovenia and Italy, are more than remnants of the past. They are messages carved in stone, whispering across millennia. They speak of cooperation, creativity, and the timeless bond between humanity and nature.

And though their builders are long gone, their story endures—a testament to our species’ greatest talent: the ability to imagine, to build, and to work together toward a vision greater than ourselves.

More information: Dimitrij Mlekuž Vrhovnik et al, Prehistoric hunting megastructures in the Adriatic hinterland, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2511908122