For more than half a century, a quiet debate simmered in the world of paleoanthropology. At its center stood Paranthropus boisei—a robust, enigmatic cousin of modern humans known for its massive teeth, wide face, and jaw muscles strong enough to crush the toughest vegetation. But behind those powerful jaws lay an enduring question: was P. boisei capable of making and using tools, or was it merely a vegetarian powerhouse that left no mark on the technological history of our species?

Now, that question may finally have an answer. A team of researchers has uncovered the first hand and foot bones unambiguously associated with Paranthropus boisei, and the results are astonishing. Published in the journal Nature, their findings reveal a creature with both the dexterity of humans and the gripping strength of gorillas—a combination that reshapes how scientists view this long-extinct relative.

Unearthing an Ancient Story

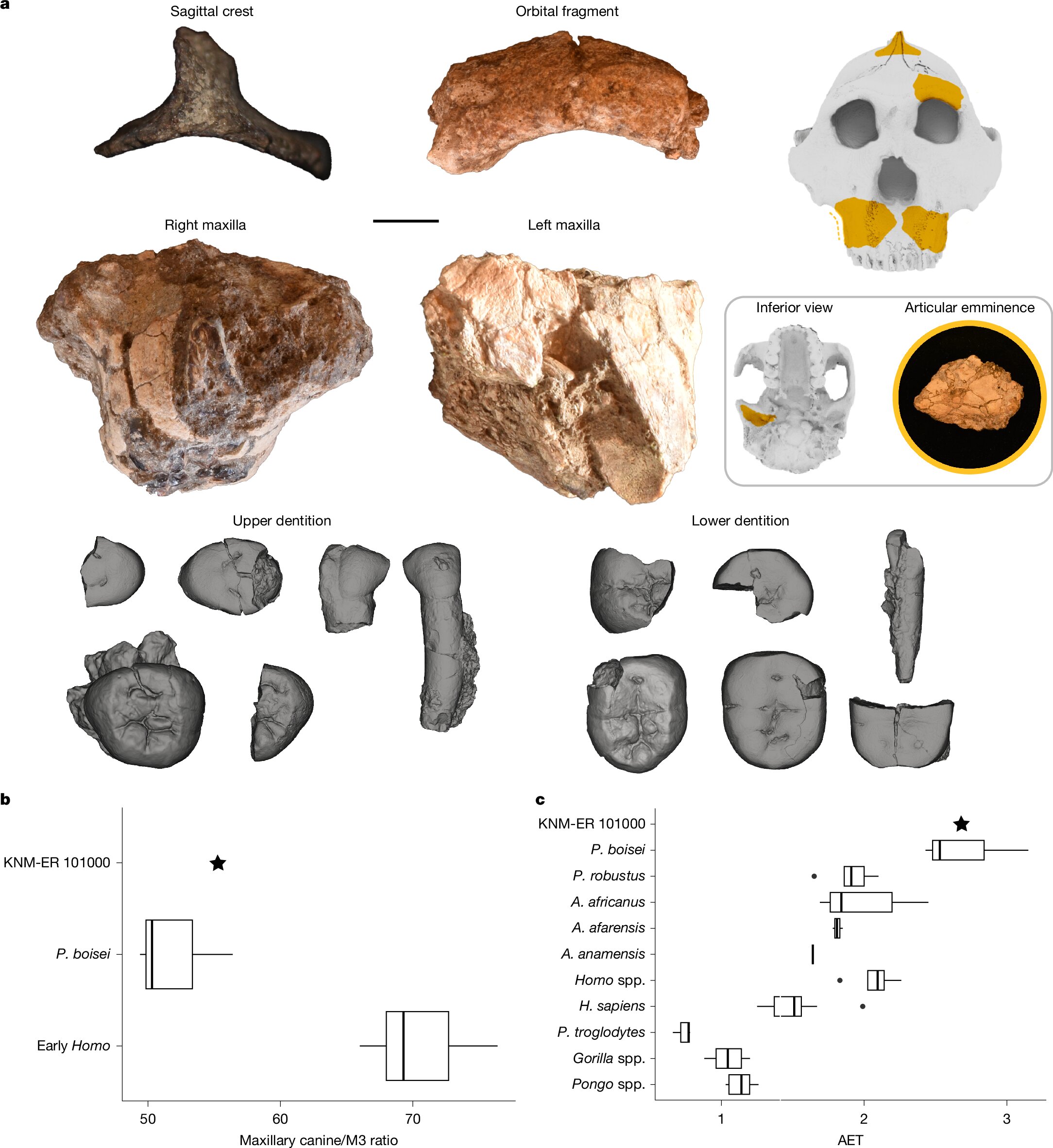

The breakthrough came from the fossil-rich region of Koobi Fora, on the eastern shores of Lake Turkana in Kenya—a landscape that has long been a window into human evolution. Between 2019 and 2021, researchers painstakingly excavated layers of ancient sediment that concealed the remains of a single individual, designated KNM-ER 101000.

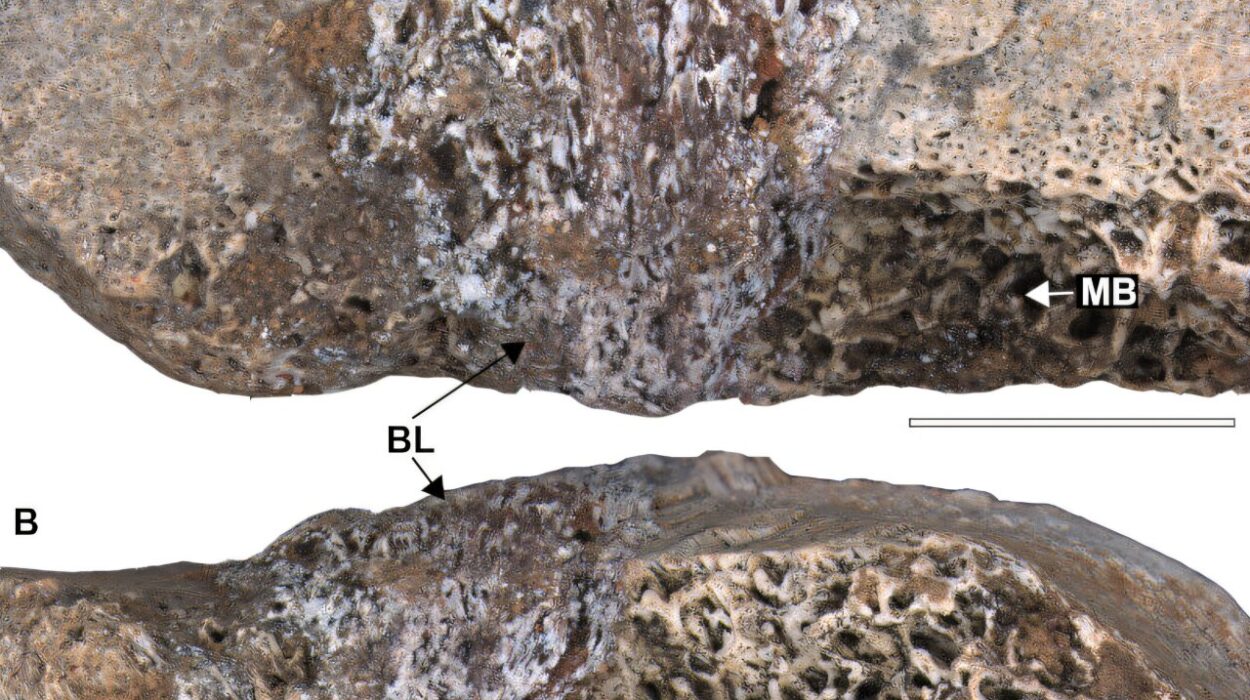

The find included cranial fragments, teeth, and, crucially, an exquisitely preserved set of hand and foot bones—the first ever confidently linked to Paranthropus boisei. These fossils, dating to just over 1.5 million years ago, offered the missing puzzle pieces scientists had sought for decades.

“It took a huge amount of time to carefully remove the sediments that ultimately revealed these amazing fossils,” said Cyprian Nyete, field director of the excavations. “We knew we were looking at something extraordinary.”

A Hand That Could Grip and Create

When paleoanthropologists examined the bones, they found something unexpected. The hand of P. boisei displayed a remarkable blend of features: proportions strikingly similar to those of early humans, suggesting fine motor skills and precision, yet with robust fingers and strong muscles that spoke of immense power.

“This discovery helps us understand a lot more about Paranthropus boisei,” explained Dr. Caley Orr, associate professor of cell and developmental biology at the CU Anschutz School of Medicine and co-author of the study. “Its hand shared similarities with our own genus Homo while evolving its own unique capabilities. It had the dexterity to manipulate objects, but also the raw strength for intense gripping—perhaps for processing tough plant foods or climbing.”

In other words, P. boisei was not the clumsy, ground-bound creature some had imagined. It could both grasp with finesse and hold with force—a combination that would have been invaluable for survival in the diverse landscapes of early Pleistocene Africa.

Walking Tall and Holding Strong

The fossilized foot bones provided further insight. Unlike the curved, grasping feet of apes, the foot of P. boisei was clearly adapted for upright walking. It shared the same weight-bearing structure and arch system found in humans, proving that this species was fully bipedal.

“The hand shows it could form precision grips similar to ours, while also retaining powerful grasping capabilities like those of gorillas,” said Dr. Carrie S. Mongle, lead author of the study and assistant professor of anthropology at Stony Brook University. “And the foot is unquestionably adapted to walking upright on two legs.”

This dual adaptation—dexterous hands and upright locomotion—places P. boisei squarely within the realm of tool-capable species. For decades, stone tools found alongside Paranthropus fossils were automatically attributed to early Homo. But now, the line between toolmaker and non-toolmaker has blurred.

The End of a Long Debate

“This fossil evidence effectively ends that debate,” said Dr. Matt Tocheri, a paleoanthropologist at Lakehead University in Canada and a co-author of the study.

For years, scientists had assumed that any stone tools uncovered at sites shared by Homo and Paranthropus must belong to Homo. After all, Paranthropus seemed too specialized—its skull and teeth suggested a plant-based diet, not the versatility and innovation associated with tool use.

But KNM-ER 101000 challenges that assumption. Although P. boisei lacked the highly specialized wrists of later humans and Neanderthals, it still had the hand proportions needed for tool manipulation. This means that early hominins outside the genus Homo may have been more behaviorally flexible than previously believed.

An Ancient Relative with a Unique Lifestyle

Even with its human-like dexterity, Paranthropus boisei was no mere copy of Homo. It carved out its own evolutionary niche—one that relied heavily on its distinctive anatomy. Its massive jaw and thick enamel were adaptations for a diet of tough, fibrous plants, perhaps roots, seeds, and stems that required intense chewing.

The new findings suggest that those same powerful hands may have helped process such foods, stripping bark or tearing apart fibrous vegetation before eating. Its gorilla-like grip would have made it adept at foraging, climbing, and manipulating plant materials in ways other primates could not.

“Paranthropus evolved its own strategies for survival,” said Orr. “Its hands show us that it wasn’t a passive forager—it actively interacted with its environment, just in a different way from early Homo.”

A Family Divided by Evolution

Paranthropus boisei is part of a side branch of the human family tree. It likely diverged from a common ancestor with Homo more than three million years ago, alongside other robust australopiths that once roamed Africa.

While early humans evolved smaller teeth, larger brains, and a growing reliance on tools and meat, Paranthropus doubled down on strength and specialization. Its lineage flourished for nearly a million years before eventually going extinct about one million years ago—perhaps unable to adapt as changing climates transformed its once-lush habitats.

The new discovery adds emotional depth to that story. It reminds us that Paranthropus was not a failed experiment in evolution, but a species that thrived in its own way—ingenious, resilient, and deeply capable.

The Human Spirit Behind the Science

This discovery is not only a triumph of paleontology but also of human collaboration. The work at Koobi Fora brought together scientists from around the world, united by a shared curiosity about our origins.

“None of this would be possible without the dedication of our local community partners,” said Dr. Louise Leakey, whose team helped recover the fossils. “They spend seven to eight months each year exploring, surveying, and excavating this region. Their commitment is extraordinary.”

For Leakey, the find carries personal meaning. Her family’s legacy is deeply intertwined with the study of Paranthropus boisei. Her grandparents, Louis and Mary Leakey, discovered the first P. boisei skull at Olduvai Gorge in 1959—a moment that transformed our understanding of early human evolution. Decades later, her parents, Richard and Meave Leakey, continued that exploration in the Turkana Basin, laying the groundwork for the current generation of scientists.

“It’s incredible to see how far the field has come since my grandparents’ discovery,” Leakey reflected. “We’re entering an exciting new era of paleoanthropology, where new technology and international collaboration are revealing details about our ancestors we never dreamed possible.”

A New Chapter in Human Origins

The discovery of KNM-ER 101000 changes more than just the image of Paranthropus boisei. It reshapes our understanding of what it means to be human.

The boundary between Homo and its relatives is no longer as clear as once thought. Dexterity, intelligence, and adaptability may have emerged in multiple lineages, not as the exclusive property of our own genus but as shared evolutionary experiments in survival.

In the rough hands of Paranthropus boisei, we glimpse a reflection of ourselves—not as direct ancestors, but as fellow travelers on the long road of evolution. Each fossil, each bone, tells a story of struggle, adaptation, and innovation written in the language of life.

The Legacy of a Discovery

More than 1.5 million years ago, on the shores of an ancient lake in Kenya, a hominin walked upright, foraged with strength and precision, and lived in a world both familiar and alien. Today, its bones whisper from the dust, telling a story that bridges the gap between human and non-human, between strength and intellect, between the past and the living present.

This new evidence does more than end an old debate—it reignites our imagination. It reminds us that the roots of our humanity run deep, tangled among the many branches of evolution. Paranthropus boisei, once seen as a side note in our story, now emerges as a vital chapter in the grand chronicle of life—a species whose hands could both hold the earth and shape it.

And in those ancient hands, we find the echo of our own.

More information: Carrie S. Mongle et al, New fossils reveal the hand of Paranthropus boisei, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09594-8