In a quiet computational space, far from cages and electrodes, a brain learned to see. It looked at patterns of dots and slowly figured out how to decide which category they belonged to. Its progress was messy and uneven. It made mistakes. It hesitated. It improved in fits and starts.

This alone would not be remarkable. Animals have done this in laboratories for years. What made this moment extraordinary was that this brain was not an animal at all. It was a computational model, built from scratch, never trained on a single scrap of animal data. And yet, when scientists compared its behavior and its internal neural activity to real animals performing the same task, the resemblance was startling.

The model did not just match performance. It matched the struggle of learning itself.

When Simulation Starts Acting Alive

The work comes from a team at Dartmouth College, MIT, and the State University of New York at Stony Brook, and it is published in Nature Communications. Their goal was bold: to build a brain model that does not simply imitate behavior, but grows it naturally from biological principles.

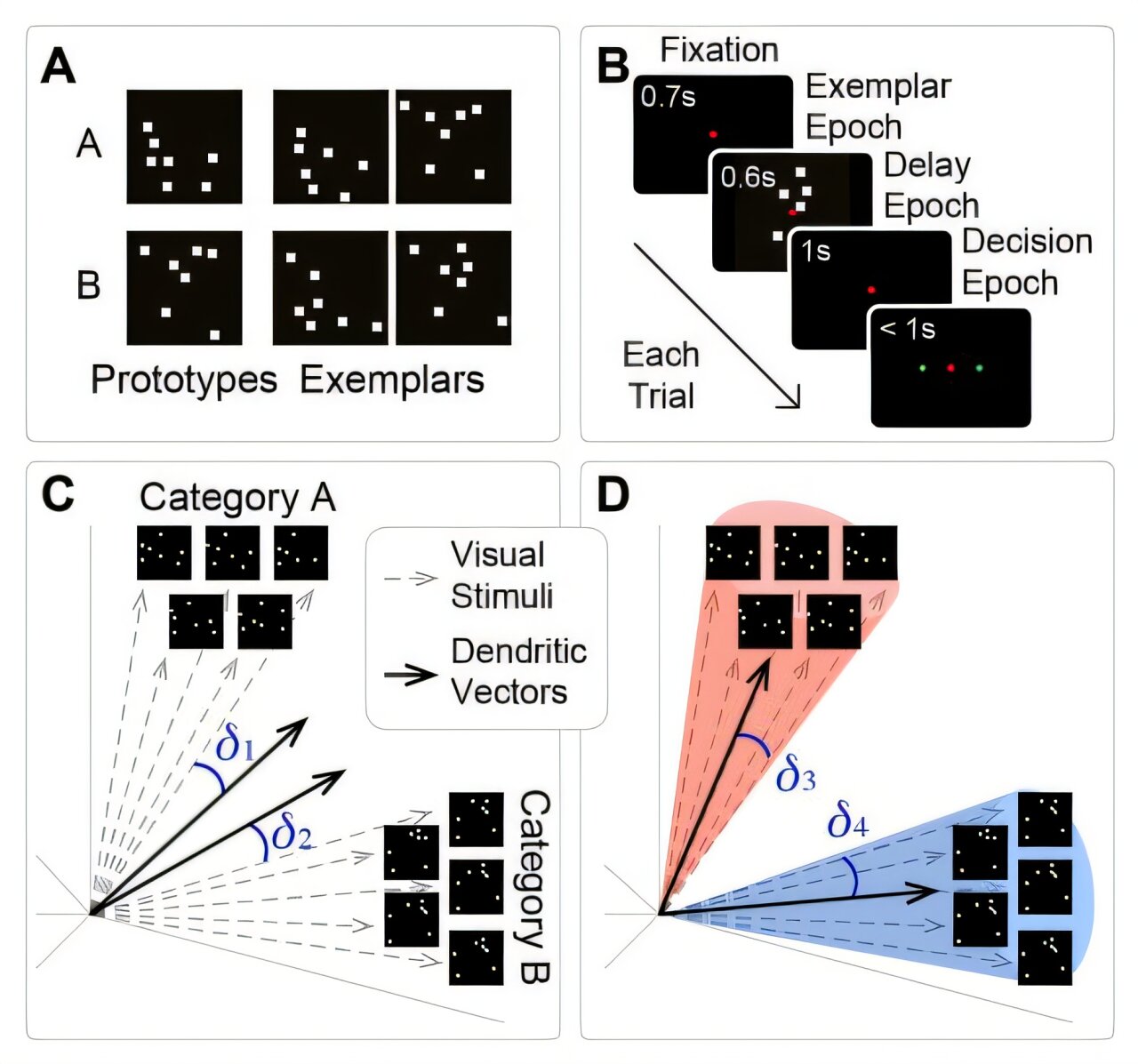

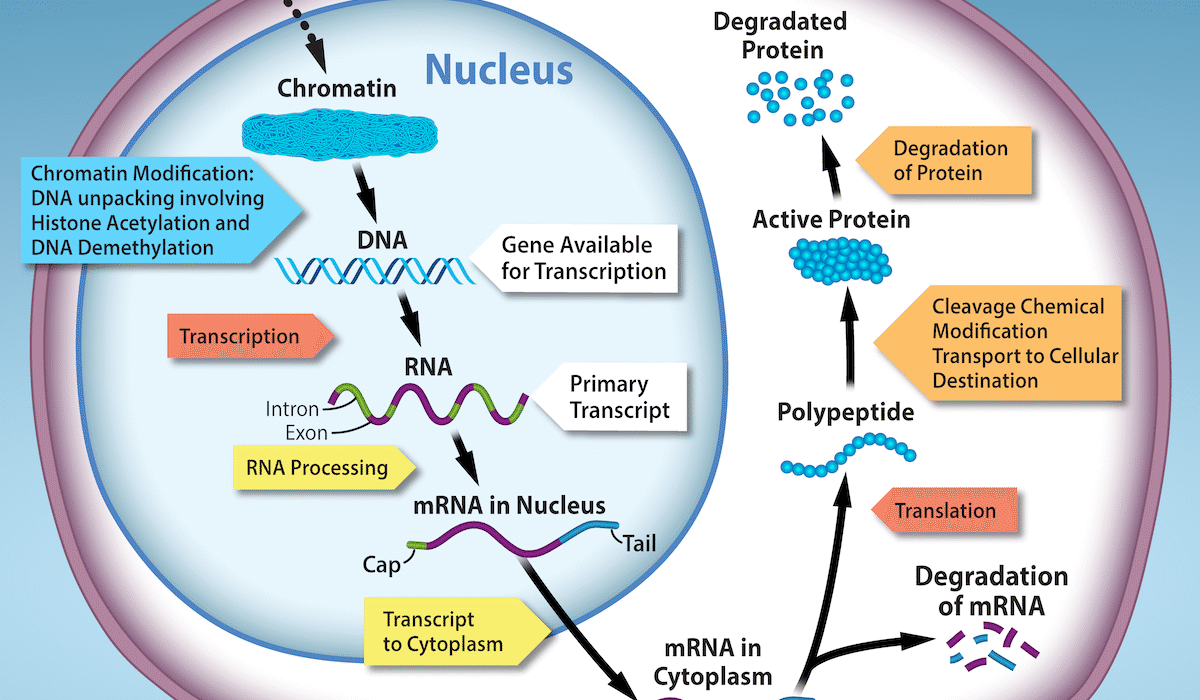

Instead of training the model on experimental data, the researchers constructed it by carefully representing how neurons connect into circuits and how those circuits communicate electrically and chemically across different brain regions. Cognition and behavior were not programmed in. They emerged.

When the researchers asked this model to perform the same visual category learning task previously given to lab animals, something unexpected happened. The model learned at almost exactly the same pace, complete with the same erratic pattern of progress. Even more striking, the simulated brain activity lined up closely with the neural data recorded from animals.

“It’s just producing new simulated plots of brain activity that then only afterward are being compared to the lab animals. The fact that they match up as strikingly as they do is kind of shocking,” said Richard Granger, a professor of Psychological and Brain Sciences at Dartmouth and senior author of the study.

Building a Brain From First Principles

The model was created by Dartmouth postdoctoral researcher Anand Pathak, who approached the challenge with a clear philosophy. Many existing brain models focus either on the fine details of individual neurons or on the large-scale interactions between brain regions. This one aimed to do both.

“We didn’t want to lose the tree, and we didn’t want to lose the forest,” Pathak said.

At the smallest scale, the model includes tiny circuits of neurons called primitives. Each primitive reflects how real neurons connect and interact through electrical signals and chemical messengers. These small circuits perform basic computational functions, much like simple building blocks that can be assembled into something far more complex.

Within the model’s version of the cortex, one such primitive includes excitatory neurons receiving visual input through synapses affected by the neurotransmitter glutamate. These excitatory neurons then connect densely to inhibitory neurons. The result is a competition where one signal dominates while others are suppressed, a “winner takes all” structure that mirrors real brain circuitry and helps regulate information processing.

At the larger scale, the model includes four major brain regions involved in basic learning and memory. There is a cortex for processing information, a striatum involved in learning actions and outcomes, a brainstem, and a structure made of tonically active neurons known as the TAN.

The TAN plays a subtle but crucial role. By releasing bursts of acetylcholine, it injects a little randomness into the system. This noise encourages the model to explore different actions instead of rigidly repeating the same response.

Learning by Wandering Before Knowing

At the beginning of the task, the model behaves inconsistently. Faced with the dot patterns, it sometimes chooses correctly and sometimes not. The TAN ensures variability, allowing the model to test different responses and observe their outcomes.

As learning progresses, something changes. Connections between the cortex and striatum strengthen. These circuits begin to suppress the TAN’s influence. The brain shifts from exploration to exploitation, acting more consistently on what it has learned.

This transition is not just theoretical. As the model learned, its internal rhythms began to resemble those seen in animals. Activity in the cortex and striatum became increasingly synchronized in the beta frequency band of brain rhythms. This synchrony peaked during moments when the model made correct judgments, precisely matching patterns observed in laboratory animals performing the same task.

For Earl K. Miller, Picower Professor in The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory at MIT and a co-author on the study, this was a familiar sight. It was a dynamic he had observed many times before in animal brains. Seeing it arise naturally in a computational model was both validating and unsettling in the best possible way.

The Neurons That Predict Failure

Then the model did something no one expected. About 20 percent of its neurons showed activity patterns that strongly predicted mistakes. When these neurons influenced the surrounding circuits, the model was more likely to choose the wrong category.

The researchers called them “incongruent” neurons.

At first, Granger and his colleagues assumed this was a flaw in the simulation. After all, why would a brain evolve cells that seem to undermine correct performance? But curiosity demanded a closer look. The team returned to the neural data they already had from animals performing the same task.

“Only then did we go back to the data we already had, sure that this couldn’t be in there because somebody would have said something about it, but it was in there and it just had never been noticed or analyzed,” Granger said.

The incongruent neurons were real.

When Being Wrong Might Be Useful

Rather than dismissing these neurons as noise, the researchers began to consider their purpose. Miller offered a compelling idea. Learning rules is valuable, but environments change. A brain that only ever follows what it already knows risks becoming trapped when conditions shift.

Trying alternatives, even wrong ones, can open doors to new strategies. The incongruent neurons may provide that flexibility, nudging the brain to occasionally question its own conclusions.

This idea aligns with recent evidence from another lab at the Picower Institute, which suggests that humans and other animals do sometimes behave this way. They deliberately deviate from known rules, creating opportunities to discover new patterns when circumstances change.

In this light, error is not a failure. It is a feature.

From Understanding Brains to Changing Outcomes

Beyond explaining how learning works, the researchers see this model as a platform for intervention. Granger, Miller, and other team members have founded a company called Neuroblox.ai to develop the model’s applications in biotechnology. Lilianne R. Mujica-Parodi, a biomedical engineering professor at Stony Brook and Lead Principal Investigator for the Neuroblox Project, serves as the company’s CEO.

The ambition is not just to simulate healthy brains, but to explore how brains might function differently in disease and how those differences could be corrected.

“The idea is to make a platform for biomimetic modeling of the brain so you can have a more efficient way of discovering, developing and improving neurotherapeutics. Drug development and efficacy testing, for example, can happen earlier in the process, on our platform, before the risk and expense of clinical trials.” said Miller, who is also a faculty member of MIT’s Brain and Cognitive Sciences department.

Since completing the work described in the paper, the team has continued expanding the model. They have added more brain regions and additional neuromodulatory chemicals. They have begun testing how drugs alter its dynamics. Each extension pushes the model closer to capturing the full complexity of real brains.

Why This Research Matters

This research matters because it suggests a new way of understanding the brain, not by forcing models to mimic data, but by allowing biological principles to generate behavior on their own. When a simulated brain, built without copying animal experiments, independently discovers the same learning curves, the same rhythms, and even the same overlooked neurons, it tells us something profound.

It tells us that the structure of the brain itself may carry more explanatory power than we realized.

This approach opens a path toward studying cognition, disease, and treatment in a space where experiments can be run safely, quickly, and ethically. It allows researchers to ask “what if” questions that would be impractical or impossible in living subjects. What if a neuromodulatory signal is weakened? What if a circuit is strengthened too much? What if error itself is essential?

Most of all, this work matters because it reframes how discovery can happen. A model built to reflect biology did not just reproduce known results. It revealed something new hiding in plain sight. In doing so, it reminded scientists that sometimes the best way to understand the brain is to let it surprise us.

More information: Anand Pathak et al, Biomimetic model of corticostriatal micro-assemblies discovers a neural code, Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-67076-x