In the sun-bleached badlands of Argentine Patagonia, where desert winds slice across ancient stone and the bones of giants sleep beneath the dust, a mystery has stirred. After more than a century of quiet slumber in museum drawers and dusty archives, one of the rarest and least understood fossil whales has reemerged to tell its story. Its name is Idiorophus patagonicus, and its tale—stitched together from fragments of fossilized bone and the relentless curiosity of modern scientists—offers a rare glimpse into the shadowy dawn of sperm whale evolution.

The study, published in the journal Papers in Palaeontology and led by paleontologist Dr. Florencia Paolucci, is a meticulous reanalysis of a single, enigmatic specimen—a partial skeleton discovered over a century ago in the Early Miocene deposits of the Gaiman Formation. It is the only known representative of its species. But in that lonely fossil, locked in stone for 20 million years, lies an evolutionary narrative as rich and dramatic as the rise of the great whales themselves.

The Curious Case of Physodon patagonicus

Our journey begins not with Dr. Paolucci, but with a Victorian gentleman named Richard Lydekker, a British naturalist with a penchant for classifying the great unknown. In 1893, Lydekker described a fossilized sperm whale skull from Argentina, christening it Physodon patagonicus. Unfortunately, the name Physodon had already been claimed—not once, but twice: first for isolated Miocene teeth in Italy, and later as a genus of sharks. Taxonomic rules demand uniqueness, and so the name was discarded like a misaddressed letter.

In 1905, Belgian paleontologist Othenio Abel proposed a new home for the fossil: Scaldicetus, a notoriously messy taxon that had become a catch-all bin for any fossil whale that didn’t fit neatly anywhere else. But it wasn’t until 1925 that American scientist Remington Kellogg—himself a legend in cetacean paleontology—offered a more fitting name: Idiorophus, derived from Greek roots meaning “peculiar crest.”

Still, for decades afterward, Idiorophus patagonicus remained in scientific obscurity—neither fully studied nor widely understood. It was a name on a shelf, a relic from a forgotten epoch. Until now.

Sleeping Giant of the Gaiman Formation

The fossil in question came from somewhere near Cerro Castillo, near Trelew in the windswept steppe of Chubut Province, Argentina. The precise location is unknown—a common issue with 19th-century fossil hunting—but the sediments of the Gaiman Formation tell their own story. They date back to the Early Miocene, a time when Patagonia was a warm coastal paradise teeming with marine life: sharks, penguins, seals, and whales.

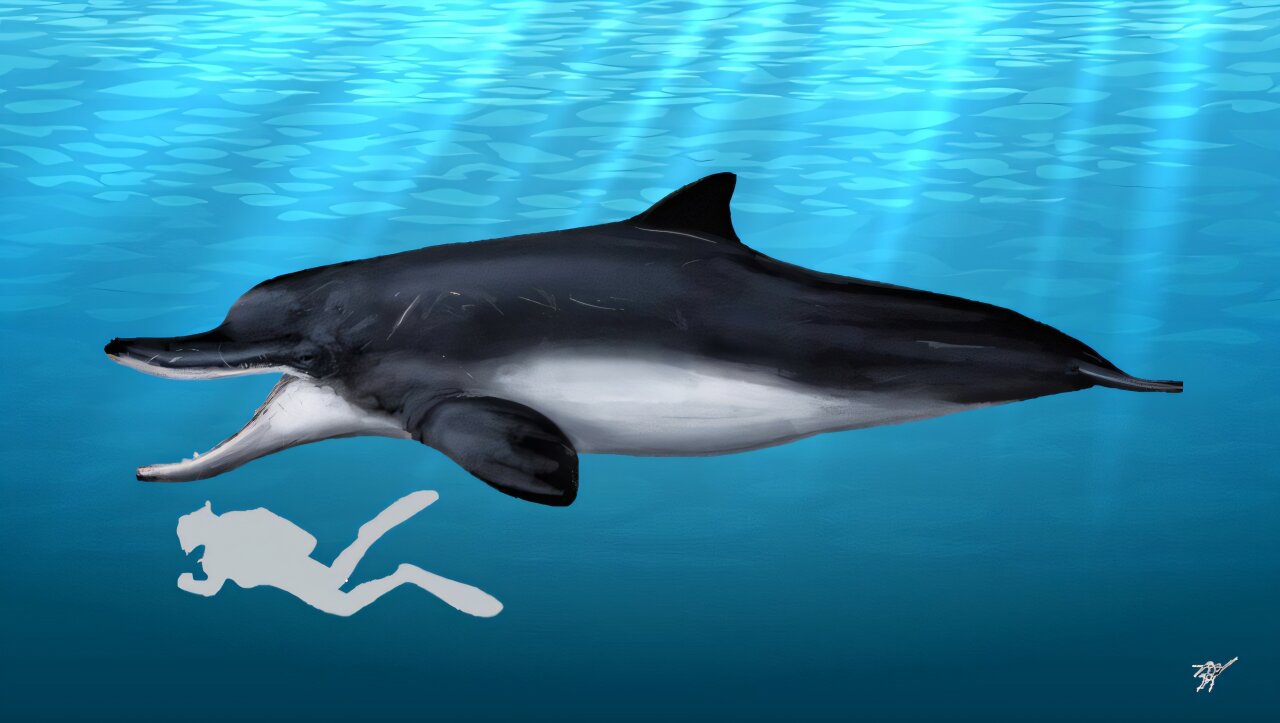

Among these ancient denizens swam the young Idiorophus patagonicus, a subadult measuring about 5 to 6 meters long. This size puts it squarely between today’s Kogia species (the dwarf and pygmy sperm whales) and the enormous Physeter macrocephalus, the living giant sperm whale capable of growing up to 20 meters long.

But Idiorophus was not merely a scaled-down ancestor of modern whales. Its anatomy—and especially its skull—suggests something much more intriguing: a predator that carved out a very different ecological niche from its modern relatives.

Teeth of a Hunter, Not a Suction-Feeder

To understand why Idiorophus matters, one must first understand how modern sperm whales feed. Today’s sperm whales are suction feeders. In the inky blackness of the ocean’s twilight zone, they hunt soft-bodied prey—mostly squid—by generating powerful negative pressure in their mouths to suck in their victims. Their lower jaws are long and narrow, filled with simple conical teeth; the upper jaw typically lacks functional teeth altogether.

But the fossilized skull of Idiorophus tells a different story.

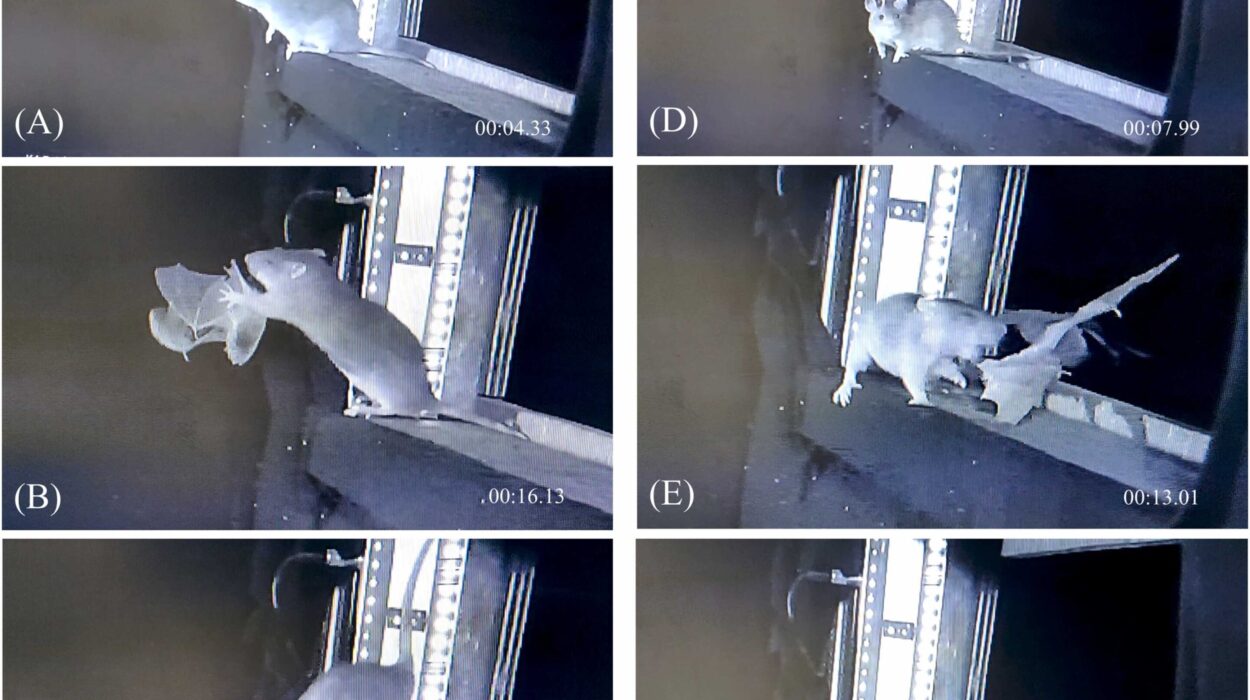

Its robust rostrum—basically, the snout—was lined with functional teeth in both jaws, suggesting an animal that captured prey using grasping and biting rather than suction. These traits are common in raptorial predators, like some dolphins or the extinct apex predator Livyatan melvillei, a Miocene sperm whale whose fossil skull revealed massive, interlocking teeth and a diet that likely included other marine mammals.

Dr. Paolucci and her team, after a careful anatomical revision, concluded that Idiorophus may have fed on large fish, and possibly even birds. “The ecomorphological features of Idiorophus point to a lifestyle quite different from that of modern sperm whales,” she explained. “It was likely an active predator.”

In evolutionary terms, this is significant. It suggests that early sperm whales experimented with diverse feeding strategies before modern forms settled into their squid-specialist niche.

A Ghost Lineage in the Cetacean Family Tree

Where exactly does Idiorophus patagonicus fit into the grand tapestry of whale evolution? The phylogenetic analysis revealed that it was not closely related to any other known physeterid species in the region. It occupies a basal position in the sperm whale family tree—either as one of the earliest branching members or possibly as the common ancestor of all physeterids.

If this is true, then Idiorophus may be the key to understanding the origins of the entire sperm whale lineage. Its morphology bridges the gap between archaic odontocetes (toothed whales) and the specialized giants we know today. It is a living fossil, or rather, a fossil that once lived, at the crossroads of evolutionary experimentation.

Anatomy Lost to Time—and Soft Tissue

Reconstructing the life of Idiorophus is a puzzle with many missing pieces. One of the great limitations of paleontology is the absence of soft tissues—muscles, blubber, blood vessels, lungs. These don’t fossilize, and yet they are critical for understanding an animal’s behavior and physiology.

In whales, for example, adaptations for deep diving—like reinforced sinuses and collapsible lungs—are largely soft tissue-based. Occasionally, bones in the skull base (the basicranium) offer hints. But in the case of Idiorophus, the basicranium wasn’t preserved.

So, we’re left to speculate. Was it a deep diver like modern sperm whales, plunging into the abyssal dark to hunt elusive prey? Or did it remain closer to the surface, stalking fish and birds in coastal waters? Its teeth suggest the latter, but without soft tissue clues, certainty remains elusive.

A Lone Specimen, A Host of Questions

Frustratingly, Idiorophus patagonicus is known from a single individual. Paleontologists crave data—multiple specimens that can show variation, pathology, growth stages. With only one fossil to study, it’s hard to say whether Idiorophus was widespread, or if it was an evolutionary offshoot that quickly blinked out.

Dr. Paolucci is candid about these limitations: “We can’t determine whether the species lasted for a longer time span—we just know it was present in the Early Miocene.” Still, even this lone fossil is a goldmine. It anchors a point in the evolutionary timeline, showing that raptorial sperm whales were prowling the seas of South America 20 million years ago.

But what happened to Idiorophus? Why did it vanish?

Extinction in the Murky Depths of Time

There is no clear record of when or why Idiorophus disappeared. No fossil cemetery holds its bones in succession. Yet its fate may mirror that of other Miocene whales—species that rose in the warm, shallow seas of a greenhouse Earth and declined as climates cooled and oceans changed.

Dr. Paolucci offers a range of possibilities. “Any hypothesis is on the table,” she says. “From global climate changes that may have altered ocean dynamics and prey availability, to potential competition with other marine mammals (e.g., dolphins).”

The Miocene was a time of dramatic tectonic and climatic upheaval. Ocean currents shifted. Antarctica became increasingly glaciated. New predators emerged, and food webs changed. These transformations reshaped marine ecosystems, and Idiorophus, it seems, did not survive the transition.

The Politics of Paleontology

If there’s one thing more precarious than a fossil in a crumbling cliff, it’s a paleontologist’s funding. For all the groundbreaking insights her study has produced, Dr. Paolucci now faces a harsh new reality: the ability to continue her work is threatened by political decisions far from the field.

“Unfortunately,” she says, “with the severe cuts to science and technology currently happening in Argentina under President Javier Milei’s government, that possibility is becoming increasingly distant.”

Science, like fossils, depends on preservation. When institutions crumble or budgets are slashed, knowledge is lost. Future Idiorophus specimens may lie just beneath the surface, but without resources, they may never be found.

Why Idiorophus Matters

In a world where billion-dollar space telescopes scan the cosmos and AI models sift data faster than human minds can grasp, one might ask: what does a single fossil whale matter?

It matters because evolution is a mosaic, and every fragment contributes to the larger picture. Idiorophus patagonicus is not just a curious relic—it’s a crucial datapoint in the story of how whales became whales. It challenges assumptions, fills gaps, and raises new questions about adaptation, survival, and extinction.

More than that, it is a symbol—a reminder that the Earth holds secrets still sleeping in its rocks, waiting for the right combination of eyes, minds, and tools to awaken them.

The Future: Still Murky, Still Worth Pursuing

Despite the uncertainty surrounding its discovery site, the missing basicranium, the lack of comparative specimens, and the grim funding landscape, Dr. Paolucci remains hopeful. Science often advances not in leaps, but in careful, quiet revisions. And sometimes, as with Idiorophus, even a century-old fossil can shake the foundations of what we thought we knew.

There are still new species to discover, evolutionary lineages to trace, and ecological dramas to reconstruct. But only if we continue to look.

The sleeping sperm whale of Patagonia has finally stirred. Now it’s up to us to listen to what it has to say.

Reference: Florencia Paolucci et al, Awakening Patagonia’s sleeping sperm whale: A new description of the Early Miocene Idiorophus patagonicus (Odontoceti, Physeteroidea), Papers in Palaeontology (2025). DOI: 10.1002/spp2.70007