For decades, the story of humpback whale migration has been told like a grand, unchanging epic: colossal creatures, bloated with blubber from months of gorging on Antarctic krill, begin their journey northward. They swim thousands of kilometers to the balmy waters of the tropics—not for vacation, but for love and life. Mating and calving occur in these warm, calm seas, far from the freezing bite of the Southern Ocean and the lurking jaws of predators. The narrative was neat, familiar, and above all, consistent.

Until now.

In a stunning twist to this well-trodden tale, scientists have revealed that humpback whales are giving birth not only in the traditional tropical breeding grounds but also much further south—along the so-called “humpback highway” that traces the eastern and southern coasts of Australia and New Zealand. These unexpected nurseries, some as far south as Tasmania and Kaikōura, New Zealand, lie 1,500 kilometers below the latitudes previously assumed safe for calving. The findings challenge everything researchers thought they knew about one of the ocean’s most iconic migrations.

And it all began with a mother and calf spotted amid the shipping lanes.

A Tiny Calf in a Big Port

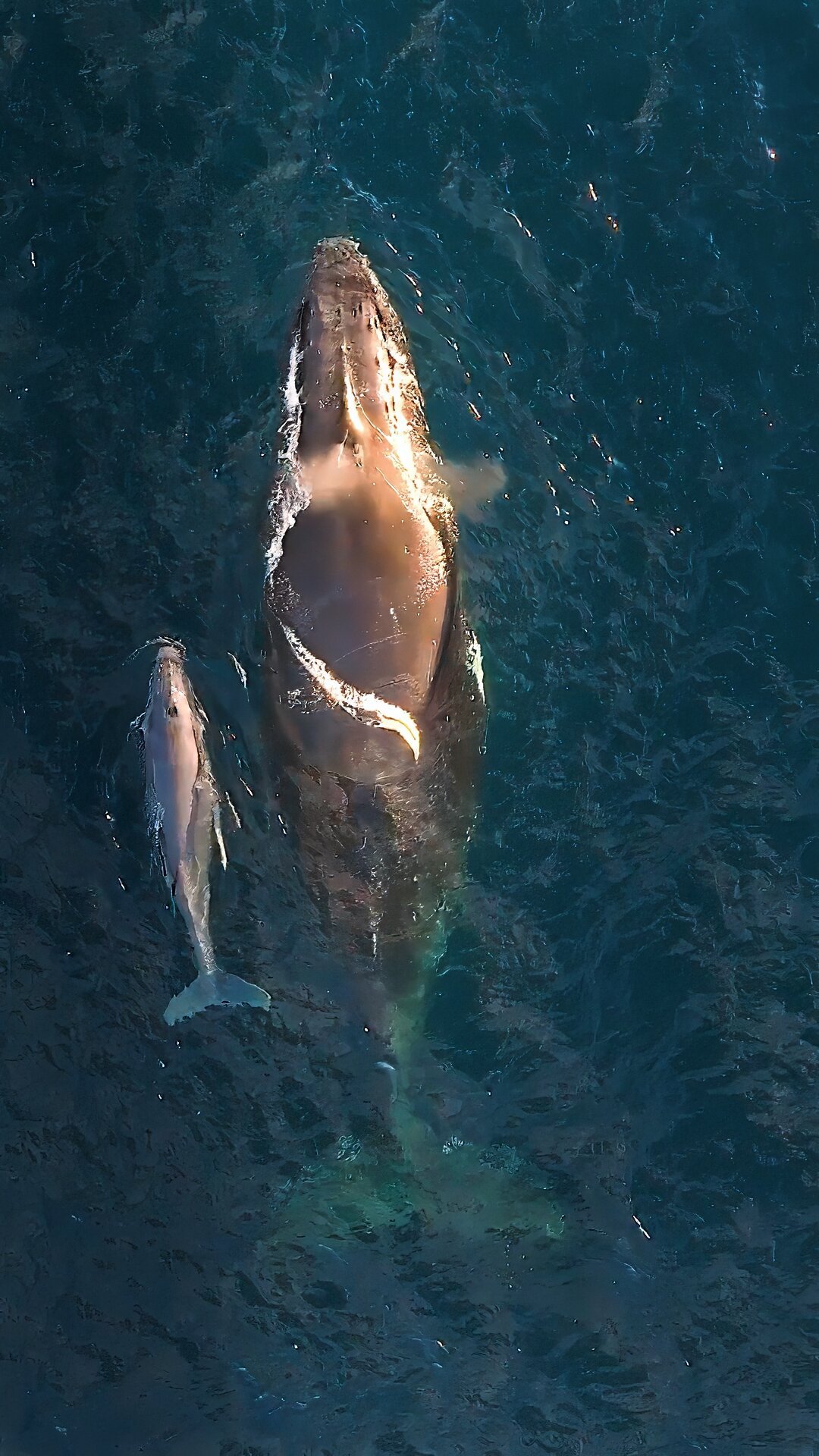

In July 2023, marine biologist and Ph.D. candidate Jane McPhee-Frew was aboard a whale-watching tour near Newcastle, one of the busiest shipping ports in eastern Australia. She spotted a humpback whale with a tiny, glistening calf nestled at her side. The calf was so small, so fresh, that it bore the unmistakable signs of having been born recently—perhaps even hours earlier. McPhee-Frew was stunned.

“What were they doing here?” she recalls wondering. “It’s not a calm, protected place. It’s an industrial harbor. But no one else on board seemed surprised. They’d seen this before.”

That sighting sparked a broader investigation, led by researchers from the University of New South Wales and several wildlife and conservation agencies. What they found, compiled from over three decades of records, was remarkable: 209 confirmed sightings of humpback calves born far south of their expected birthing areas. Of those, 168 were live calf observations, 41 were recorded strandings, and 11 were confirmed births. The data came from citizen scientists, government agencies, whale-watching logs, and even 19th-century whaling records.

Calves had been born, it turned out, all along the humpback highway.

Birth Beyond the Tropics

The southernmost confirmed calf was found near Port Arthur, Tasmania—a location far removed from the turquoise warmth of tropical Queensland or northern Western Australia. Another was spotted in Kaikōura, a remote stretch of New Zealand’s rugged coast known more for deep ocean canyons and giant squid than baby whales.

Historically, scientists believed that giving birth in cold waters was simply too dangerous for newborn humpbacks. Calves are born with a thin layer of blubber and rely on warm seas to conserve energy and grow stronger before migrating. But these findings suggest that humpback whales can be far more adaptable than previously imagined.

Senior author Dr. Tracey Rogers, from the University of New South Wales, notes, “Hundreds of calves were born well outside the established breeding grounds. These vulnerable calves are not yet strong swimmers. Giving birth during migration means they’re forced to swim long distances earlier in life, with greater exposure to predators and hazards.”

Indeed, researchers found that many of the newborns began heading north immediately after birth—following the ancient migratory route that was supposed to lead them to their birthplace, not away from it.

Migration Under the Microscope

Why then, do humpbacks migrate at all? If birthing outside tropical breeding grounds is feasible—if not optimal—why undertake the enormous, energetically costly journey?

The answer, as with much of nature, is not simple. Migration may be driven by a suite of factors beyond temperature. Tropical waters provide not only warmth, but safety: they’re relatively predator-free and calm, reducing the physical demands on calves in their first weeks. The nutrient-rich cold waters of the Southern Ocean, in contrast, teem with killer whales and demand constant swimming just to maintain body heat.

Yet the pattern of far-south births isn’t necessarily new. Co-author Jane McPhee-Frew points out that early whaling logs recorded similar observations of young calves seen mid-migration. But during the 20th century, whale populations were decimated by industrial whaling. With only a few thousand individuals left in some populations, rare events—like births outside the tropics—became vanishingly unlikely, or simply went unseen.

“The Eastern Australia humpback population narrowly escaped extinction,” says McPhee-Frew. “But now we’re seeing 30,000 to 50,000 individuals in that group alone. As the population rebounds, so does the full diversity of their behavior.”

The past, in other words, is reasserting itself.

Conservation in the Shadow of Recovery

The discovery of these unexpected calving areas isn’t just a scientific curiosity—it carries real conservation consequences. Unlike the quiet lagoons of the tropics, the “highway” is busy, loud, and dangerous. Newborn calves face increased risks from boat traffic, fishing lines, pollution, and even entanglements with marine debris. Some of the calves observed in the study bore fresh injuries, raising concern about how well they can survive their early days outside protected zones.

McPhee-Frew warns, “These births are happening in areas that aren’t designed to protect young whales. We need to rethink where and how we enforce marine protections.”

One possible nursery area, identified with help from Western Australia’s Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, is Flinders Bay. Yet even there, awareness and regulations may lag behind the shifting whale behavior. Expanded calving grounds call for expanded vigilance.

Dr. Adelaide Dedden of Australia’s National Parks and Wildlife Service emphasizes that the whales’ migratory energy budget is not limitless. “They rely heavily on body reserves built from Antarctic krill to fuel reproduction,” she explains. “Migration is costly. Giving birth along the way uses up those resources faster.”

The question becomes: are these mid-route births a choice, or a necessity?

Whale Maternity: Opportunistic or Strategic?

Are these southern births rare accidents—early labors gone wrong—or are they a natural part of humpback reproductive behavior that scientists simply failed to recognize?

It’s too early to say definitively, but the trends are intriguing. Most live calf observations occurred after 2016, and two-thirds were recorded in the last two years, 2023 and 2024. This uptick might reflect increased whale numbers, better surveillance, or both. Smartphone cameras, social media sharing, and heightened eco-tourism have likely contributed to a boom in citizen science.

Still, McPhee-Frew urges caution. “This was a study based on opportunistic sightings. We can’t stretch the conclusions too far. We only know what we can see, and we may be seeing more because more people are looking.”

Co-author Dr. Vanessa Pirotta, a whale researcher at Macquarie University, agrees. “There may be things happening in our oceans that we are yet to understand. Whale behavior is complex, and we’re just beginning to scratch the surface.”

A Changing Ocean, A Changing Story

The oceans today are not the oceans of the past. Climate change, shifting currents, and human activity are transforming marine environments in ways we don’t yet fully grasp. Whale migration patterns, long thought to be immutable, may be evolving in response.

It’s possible that warming waters are extending the range of viable birthing areas southward. Or perhaps whales, adapting to increased population pressures, are taking risks they once avoided. These new findings may reflect the flexibility of a species rebounding from the brink.

Einstein famously said that “the most beautiful experience we can have is the mysterious.” The mystery of the migrating, birthing humpback is one of those beautiful experiences—a story in motion, with each new calf a punctuation mark on a sentence still being written.

Whales, Watching Us

In the end, this study isn’t just about whales changing their behavior. It’s about how human knowledge changes too—how science, like nature, is always moving.

The long-held idea of a singular birthing destination, a sacred tropical nursery, has now given way to a more dynamic, more complex understanding. As the humpback whale population continues to grow and rebound, so too does our appreciation for their resilience and versatility.

But with that appreciation must come responsibility.

The calves born along the humpback highway are vulnerable not only because they are small and fragile, but because they are invisible to laws, protections, and awareness campaigns that have been focused elsewhere. To keep pace with the whales, we must extend our protection further south—and our curiosity even further.

For now, mother whales and their tiny calves continue their journey northward—through busy harbors, along jagged coasts, past fishing boats and echoing engines. And we, once again, are reminded that the wild world does not obey our maps.

Reference: Humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) continue migration after giving birth in temperate waters in Australia and New Zealand, Frontiers in Marine Science (2025). DOI: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1545526