The world around us is not static. It is alive, changing, pulsing with movement—not just in the obvious rise and fall of seasons, or the blooming and dying of flowers, but in a deeper way that speaks to time itself. Evolution is not merely a concept locked away in dusty textbooks or ancient fossils buried beneath rock. It’s a living, breathing reality, unfolding right now in the birds outside your window, the bacteria in your gut, and the crops on your dinner plate. You don’t need a microscope or a time machine to see it. You just need to look—closely, curiously, and with wonder.

Evolution is not a theory confined to ancient history. It’s the most powerful explanation we have for how life has changed over time, and crucially, how it’s still changing. While many people imagine evolution as something that happened long ago—dinosaurs transforming into birds, or fish crawling onto land—the truth is more thrilling. The evidence for evolution is all around us, unfolding in real time, visible in the ordinary and the extraordinary alike.

The Peppered Moth and the Shadow of Industry

Let’s begin with something as simple as a moth. In 19th-century England, the peppered moth was predominantly pale with dark speckles—a coloring that helped it camouflage against the light-colored bark of trees. This camouflage protected it from predators like birds.

Then came the Industrial Revolution. Factories belched soot into the air, darkening the bark of trees. Suddenly, the once-camouflaged pale moths stood out, making them easy prey. A previously rare form of the moth, one that was almost entirely black, began to thrive. By the late 1800s, black moths had replaced the pale ones in heavily polluted areas. When air pollution laws cleaned the skies in the 20th century, the trend reversed: light-colored moths returned to dominance.

This is natural selection in action. The moths didn’t choose to change. They didn’t evolve during their lifetimes. But those with traits better suited to their environment survived and passed those traits on. The moths were simply following the rules of survival, shaped by changes in their surroundings. In less than a century, they became living proof of evolution responding to human influence.

Antibiotic Resistance: Evolution at the Speed of Life

If you’ve ever had a bacterial infection, odds are you’ve taken antibiotics. And if you’ve ever been warned to finish the full course of your medication, even if you feel better, it’s because of evolution.

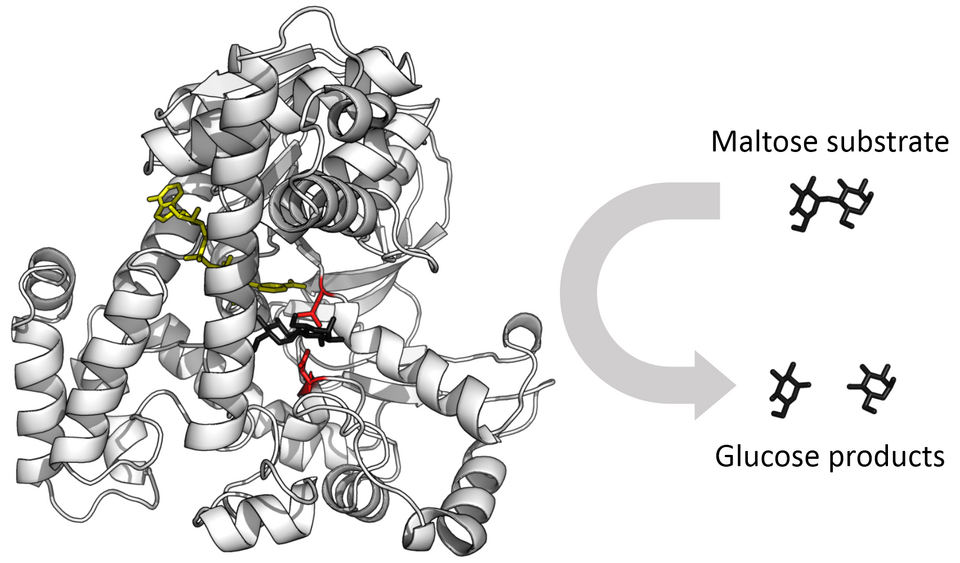

When bacteria are exposed to antibiotics, most die—but not all. Some carry random mutations that make them resistant. These survivors reproduce, passing on the resistance to the next generation. In time, entire bacterial populations can become immune to drugs that once wiped them out.

This is not a slow process. Bacteria multiply rapidly—some doubling every 20 minutes. In hospitals, farms, and even homes, we’re seeing the rise of so-called “superbugs,” bacteria that shrug off multiple antibiotics. These aren’t futuristic threats. They are evolving right now in clinics and kitchens, an unintended consequence of our own medical advances.

Antibiotic resistance is evolution under a microscope, moving at lightning speed. It’s one of the most dangerous modern examples of how quickly life can adapt, and why understanding evolution is not just academic—it’s urgent.

The Domesticated World: Evolution in Our Hands

Look at your dog. Whether it’s a Chihuahua or a Great Dane, it descended from wolves. Not long ago in evolutionary terms—perhaps 15,000 years—humans began to tame wolves. They chose the ones with less aggressive behavior, with traits that made them better companions. Over generations, this selective breeding gave rise to the incredible diversity of dog breeds we see today.

Dogs are not alone. Cows, pigs, sheep, corn, wheat, bananas—all have been transformed through artificial selection. We have changed their genes by choosing which individuals to breed. The wild ancestors of these organisms often bear little resemblance to their modern descendants.

This kind of evolution doesn’t require millions of years. It happens whenever selection—natural or artificial—pushes a population toward certain traits. The power of evolution has been harnessed by humans for thousands of years, shaping the living world into forms that suit our needs, tastes, and desires.

The Dance of Finch Beaks in the Galápagos

Charles Darwin’s journey aboard the HMS Beagle in the 1830s took him to the Galápagos Islands, where he observed finches with beaks of varying shapes and sizes. Each beak type was suited to different food sources—thick beaks for cracking seeds, slender ones for catching insects. This observation helped inspire the theory of natural selection.

But what Darwin saw in a snapshot, modern scientists have watched unfold in real time.

In the 1970s, researchers Peter and Rosemary Grant began studying finches on the island of Daphne Major. They meticulously recorded the size and shape of beaks, the number of offspring, and the availability of food over decades. During drought years, only large, tough seeds remained, favoring finches with bigger beaks. In just a few generations, the average beak size increased. Later, when smaller seeds returned, so did smaller beaks.

These were not abstract ideas—they were measurable changes in a natural population, driven by environmental conditions. The Grants’ work offered a stunning, detailed view of evolution occurring year by year, shaped by survival and reproduction.

Vestigial Echoes: The Ghosts of Evolution in Our Bodies

Not all evidence for evolution comes from change. Some of it lingers in the form of leftovers—traits that no longer serve their original function. These are called vestigial structures, and they’re everywhere, including inside your own body.

Consider the human appendix. Once believed to be useless, it’s now thought to have a minor immune function, but its evolutionary roots likely trace back to herbivorous ancestors who used it to digest cellulose-rich plants. It has shrunk over time as our diets changed, but it remains a relic of our evolutionary past.

Wisdom teeth are another leftover. Our early ancestors had larger jaws and needed the extra molars to chew tough plant matter. As diets softened and jaws shrank, these teeth became problematic. Now, many people need them removed.

Even the muscles that allow some animals to move their ears still exist in humans, though most of us can’t use them. Goosebumps? A response inherited from furry ancestors, where piloerection puffed up hair to appear larger or retain heat.

Our DNA carries similar echoes. “Junk” DNA, once thought to be meaningless, contains segments that no longer code for proteins but hint at ancient genes once active in our evolutionary predecessors. Our very bodies are museums of evolutionary history.

Evolution in the Urban Jungle

Nature doesn’t only evolve in remote islands or prehistoric forests. It evolves in cities, in suburbs, and on the sidewalks where pigeons peck for crumbs.

Urban evolution is a growing field that examines how organisms adapt to manmade environments. City pigeons, for example, are descendants of wild rock doves that have adapted to urban life. Some populations show changes in color or behavior compared to rural ones. Rats, squirrels, and raccoons have developed new strategies for surviving in human-dominated spaces.

A fascinating example involves the white clover plant. In many cities, clover has evolved to stop producing a toxic chemical that deters herbivores. In natural environments, this chemical is crucial, but in cities—where fewer herbivores exist and winters are harsher—it can actually be a liability. So city clovers have evolved to drop the trait.

Even mosquitoes have evolved to adapt to the London Underground. A unique population, genetically distinct from above-ground mosquitoes, has developed that prefers human blood, breeds year-round, and thrives in the dark tunnels. Urban environments are not evolutionary dead zones—they are active laboratories of adaptation.

Human Evolution: Still in Motion

Many people assume human evolution stopped once we began building civilizations. But this is far from true. Our bodies, brains, and genes are still evolving, often in response to changes we’ve made to our environment.

Lactose tolerance is a striking example. Most mammals, including humans, lose the ability to digest milk after infancy. But in some human populations, particularly in Europe and parts of Africa, adults evolved the ability to produce lactase, the enzyme that breaks down lactose. This change emerged in societies that domesticated animals and consumed milk, offering a clear survival advantage.

Skin color is another evolutionary adaptation. As humans migrated out of Africa, those living in northern regions with less sunlight evolved lighter skin to synthesize vitamin D more efficiently. Conversely, populations near the equator retained darker skin to protect against UV radiation.

High-altitude populations, like Tibetans and Andean highlanders, have developed genetic adaptations that allow them to thrive in low-oxygen environments. These aren’t just cultural shifts—they are evolutionary responses written into our genes.

Human evolution continues in subtle ways: disease resistance, dietary adaptations, even brain structure. In the age of gene editing, reproductive technologies, and global travel, we may be shaping our own evolutionary future in ways we don’t yet fully understand.

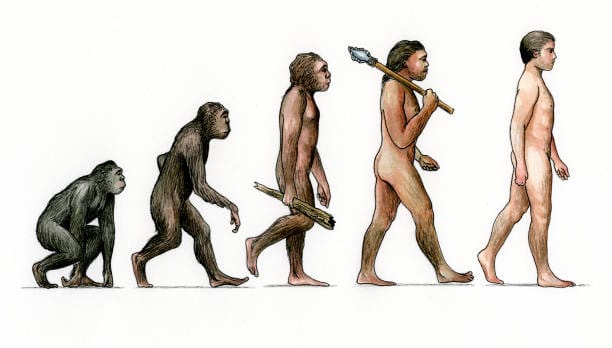

The Fossil Trail and the Living Ladder

While this article focuses on the evolution we can see around us today, it’s worth remembering that the fossil record also continues to grow. New discoveries continually bridge gaps once thought unbridgeable.

Feathered dinosaurs in China, transitional fossils like Tiktaalik (a fish with limb-like fins), and the gradual changes seen in hominin skulls all support the evolutionary story. But it’s not just about dusty bones. It’s about the patterns we see—about how traits appear, transform, or disappear over time.

Today’s living creatures carry this story forward. Whales still have tiny pelvic bones, remnants of their land-dwelling ancestors. Snakes retain vestiges of legs in their skeletons. Birds hatch with traces of dinosaurian features. Evolution is not just history—it’s continuity.

Why Seeing Evolution Matters

Understanding that evolution is happening now is more than an academic exercise—it changes how we relate to the world. It reminds us that nature is dynamic, that the species we share this planet with are not static characters in a frozen drama, but evolving beings on journeys of their own.

It teaches us humility, as we see ourselves not as separate from nature, but as part of it—products of billions of years of change, adaptation, and chance. It offers us tools to confront modern challenges, from antibiotic resistance to conservation, from agriculture to climate resilience.

Most of all, it awakens a sense of wonder. To watch a population of birds adapt to drought, or a plant adjust to city life, is to witness life responding, surviving, and shaping itself in real time. It is to see nature not as a painting, but as a poem still being written.

A Universe in Motion

Every sparrow that changes its song to compete in a noisy city. Every virus that mutates to evade our defenses. Every flower that shifts its blooming time with the changing climate. All are chapters in the same magnificent, ongoing story.

Evolution is not just something that happened. It’s something that is happening—now, today, all around you.

So the next time you look at the pigeons on your street, or take a pill for an infection, or watch your pet dog tilt its head in curiosity, remember: you are watching evolution. You are living inside it.

You are not just a witness to the story of life. You are a part of it.