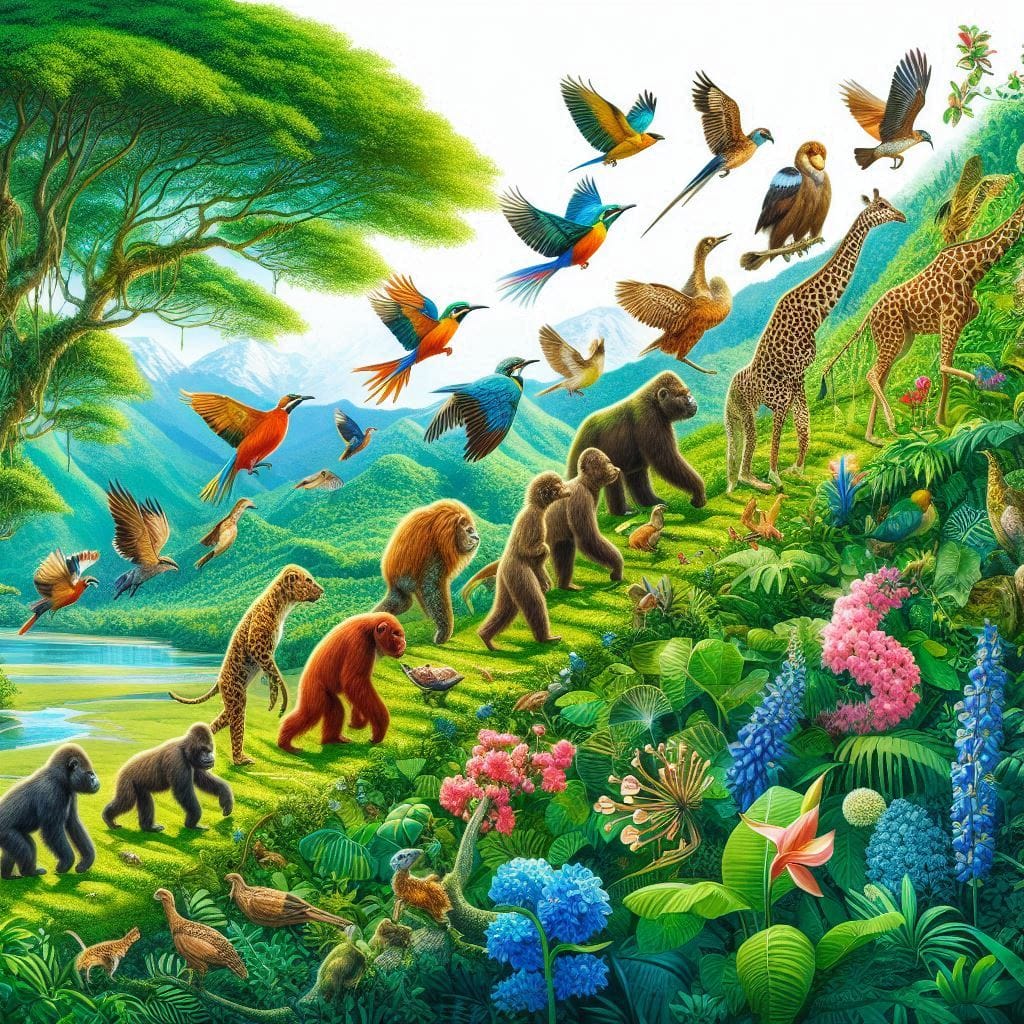

When we gaze out at the dazzling panorama of life on Earth—the flocks of birds cutting across the sky, the coral reefs teeming with strange and colorful creatures, the forests echoing with songs of insects and mammals—it’s hard not to feel overwhelmed by nature’s endless creativity. From microscopic bacteria to majestic elephants, from desert cacti to rainforest orchids, the variety of life forms on this planet is both bewildering and breathtaking.

What’s perhaps even more astonishing is the idea that all of this—every feather, fin, and flower—arose from a single, simple process: evolution. Not directed by a grand designer or orchestrated by a conscious force, but driven by natural laws, chance, and time. Evolution is not merely a theory; it is the engine behind the diversity of life itself. It sculpts organisms across generations, building complexity and adapting life to nearly every imaginable environment. It is the invisible hand that shapes existence.

Yet evolution is often misunderstood. Many people see it as a dry concept, something that happened long ago to creatures that no longer exist. But evolution is not ancient history—it’s an ongoing symphony. It’s happening in the forests and oceans, in our own bodies, and even in the cities we build. It is the thread that connects all life on Earth, past and present. And it is the story of how we came to be.

Life’s Humble Origins

To understand how evolution shapes the diversity of life, we must first go back to the beginning—not to the age of dinosaurs or even the earliest animals, but to a world before complexity, before even cells. Around 3.8 to 4 billion years ago, the Earth was a very different place: hot, volcanic, and chaotic. Yet in some ancient tide pool or deep-sea vent, something extraordinary happened. Simple molecules, perhaps by random collisions and chemical reactions, formed the first self-replicating entities.

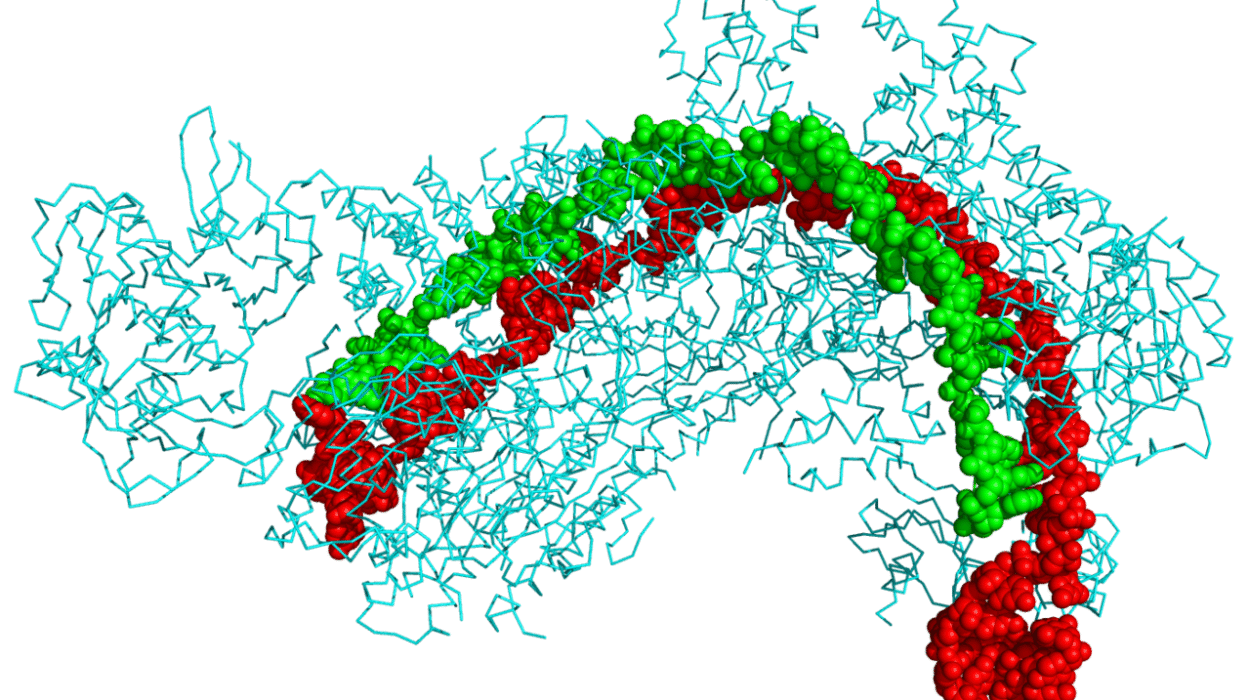

These were not yet living cells as we know them, but precursors—organic molecules capable of copying themselves, a bit like RNA. Over time, some of these molecules became encased in lipid membranes, forming protocells. Through countless cycles of copying, error, and selection, these primitive forms eventually gave rise to the first true cells: simple, single-celled organisms.

This moment—life’s origin—was the dawn of evolution. For once replication begins, so does variation. And where there is variation, nature begins to favor some forms over others.

Variation: The Raw Material of Evolution

Life is never perfect. Every time an organism reproduces, whether it’s a bacterium dividing or a bird laying eggs, small changes occur. These changes—mutations—are the sparks that drive evolution. Most mutations are neutral or even harmful. But occasionally, one offers an advantage: a slightly better way to digest food, a new shade of color that blends in better with the surroundings, a longer wing that makes flight more efficient.

These advantageous traits tend to get passed on. This is natural selection in action: the process by which traits that improve survival and reproduction become more common in a population over time. Evolution doesn’t “design” with foresight; it tinkers blindly. But over vast timescales, the accumulation of tiny changes can result in profound transformations.

One of the most powerful aspects of evolution is its ability to generate novelty. Given enough time, a single lineage can diversify into many, each adapted to a slightly different environment. This is how one kind of finch on the Galápagos Islands gave rise to a dozen, each with a unique beak shape suited to different kinds of seeds. It’s how a few ancestral mammals, after the extinction of the dinosaurs, radiated into bats, whales, cats, and primates. Evolution takes life’s raw material—variation—and sculpts from it the full panorama of biological diversity.

Adaptation and the Environment’s Guiding Hand

No species exists in isolation. Every organism is shaped not only by its genetic code but also by its environment. The cold pushes animals to grow thicker fur. High altitudes drive changes in blood chemistry. Islands isolate populations, leading to odd and wonderful adaptations—giant tortoises, flightless birds, miniature elephants.

Adaptation is the dance between organism and environment. When the environment changes, evolution must respond—or life faces extinction. Sometimes this response is fast. Bacteria can evolve resistance to antibiotics in mere months. Mosquitoes adapt to pesticides within a few generations. But for more complex organisms, adaptation is slower, often taking thousands or millions of years.

This intimate relationship between life and environment means that every ecosystem is a living portrait of evolution’s influence. The desert’s survival specialists, the rainforest’s layers of interdependent species, the deep ocean’s ghostly fish and glowing invertebrates—all are outcomes of millions of years of trial and error, of life testing every possible way to survive, and keeping what works.

Speciation: The Tree of Life Grows

The sheer variety of life on Earth is not just the result of change within species, but of the branching process known as speciation. When populations of the same species become isolated—by geography, behavior, or ecology—they begin to evolve independently. Given enough time, their differences accumulate until they are no longer able to interbreed. A new species is born.

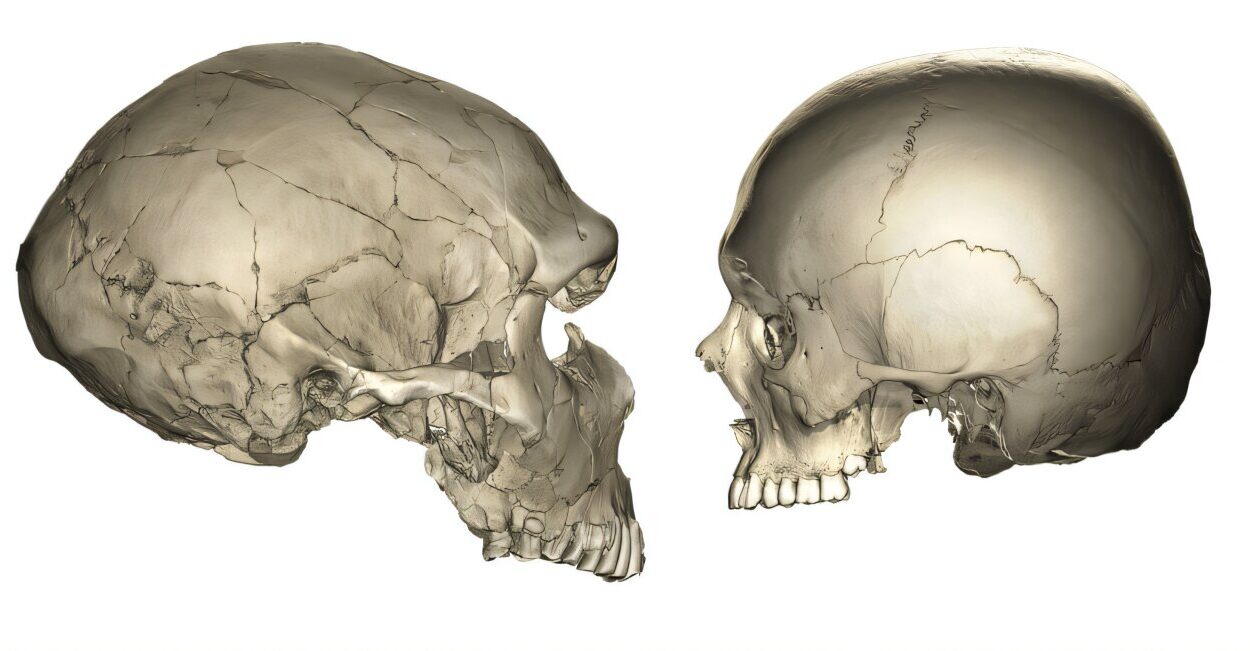

This branching pattern is what gives rise to the “tree of life,” a metaphor that Darwin himself used. All living organisms share a common ancestor if we trace far enough back in time. The bacteria and blue whales, the mushrooms and humans—all diverged from shared lineages in the ancient past.

Speciation explains how the same ancestral bird could give rise to both hummingbirds and ostriches. It’s how mammals could diversify into burrowing moles, soaring bats, and aquatic dolphins. It’s how flowering plants could evolve into over 300,000 species, painting the Earth with every imaginable hue and shape.

This tree is not just a historical curiosity. It is alive today. We see new species forming in isolated lakes, on islands, even in cities. Evolution’s creativity has never stopped.

Mass Extinction and the Reset Button of Life

While evolution builds, it also destroys. Earth has witnessed at least five mass extinction events—times when a large fraction of all species vanished, often due to sudden environmental catastrophes. The most famous of these is the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction, around 66 million years ago, when an asteroid impact wiped out the dinosaurs and many other life forms.

These events are devastating, but they also reset the stage. After the dinosaurs disappeared, mammals—once small and nocturnal—rose to dominance. After each mass extinction, evolution enters a period of rapid experimentation, filling the ecological gaps left behind. It’s a sobering reminder that life is resilient, but not invincible. Diversity is hard-won, and often temporary.

Today, many scientists believe we are living through a sixth mass extinction, driven not by natural causes but by human activity—habitat destruction, pollution, climate change, and overexploitation. Understanding evolution helps us see the urgency of this crisis, and perhaps, find better ways to protect life’s diversity before it vanishes.

Coevolution: Life Shapes Life

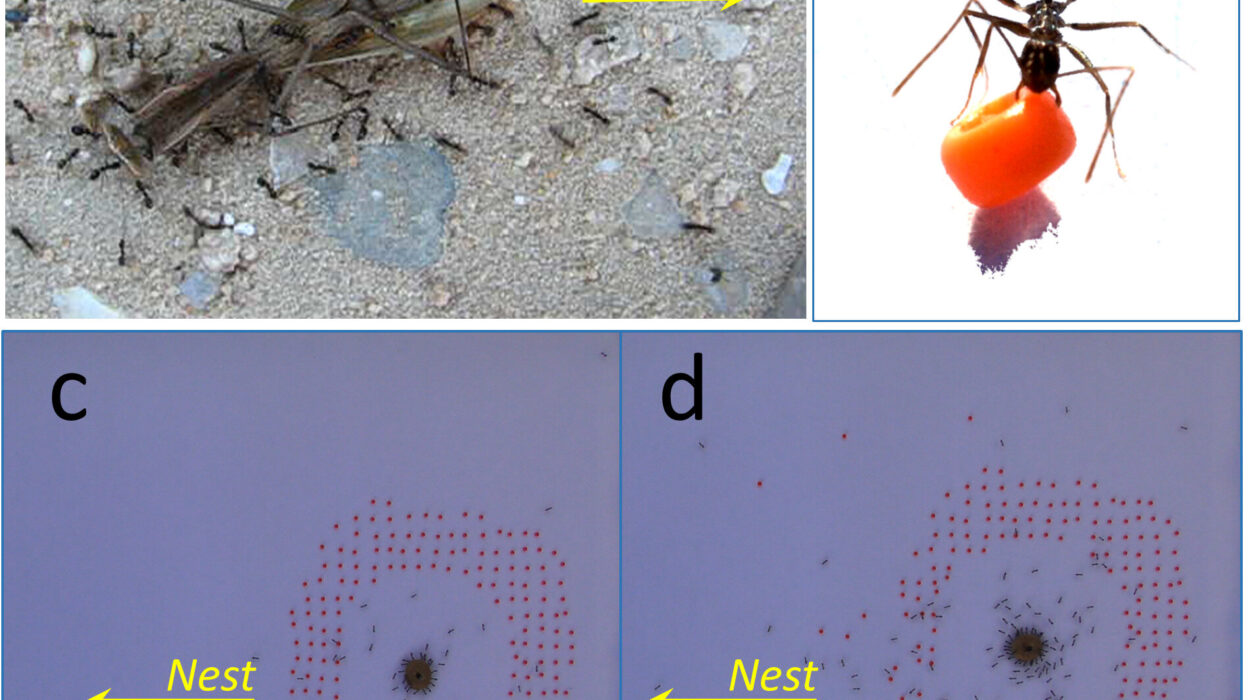

One of evolution’s most elegant processes is coevolution—when two or more species evolve in response to each other. This is the secret behind the exquisite match between flowers and their pollinators, predators and prey, parasites and hosts. Each shapes the evolution of the other in an endless arms race or delicate partnership.

Take the orchid with a flower shaped to match the tongue of a single moth. Or the cheetah and the gazelle, both locked in a sprinting contest that pushes each to new extremes. Or humans and their gut bacteria, which have co-evolved for mutual benefit over millions of years.

These relationships create networks of dependence and complexity. Ecosystems are not just collections of species—they are tapestries woven by coevolution. When one thread is pulled out, the entire fabric may fray.

Evolution in the Modern World

Though often seen as a relic of the past, evolution is very much alive in the present. We see it in the rise of drug-resistant bacteria—superbugs that outpace our antibiotics. We see it in invasive species adapting to new environments, in crop pests evolving resistance to chemicals, in viruses mutating faster than our vaccines can keep up.

Urban evolution is a new frontier. Birds in cities sing higher-pitched songs to be heard over traffic. Insects evolve resistance to industrial pollutants. Rats, pigeons, and microbes are evolving side by side with us, responding to the strange new ecosystems we create.

And humans themselves are still evolving. Changes in diet, medicine, and culture affect our bodies and genes. Some populations are evolving resistance to malaria or lactose tolerance into adulthood. Evolution has not ended—it simply moves at the pace of generations.

The Role of Randomness and Chance

One of the most misunderstood aspects of evolution is the role of chance. While natural selection is a non-random process—it favors traits that aid survival—the mutations that fuel it are random. Moreover, some changes in a population arise not from selection at all, but from genetic drift: random fluctuations in gene frequencies.

This randomness means that evolution is not a ladder of progress, but a branching, unpredictable journey. Intelligence, consciousness, and culture are not inevitable outcomes—they are rare, lucky accidents. If we could rewind the clock of life and start over, the result might look completely different. The Earth might teem with alien creatures—intelligent octopuses, perhaps, or giant insects.

Evolution’s beauty lies not in its predictability, but in its capacity for surprise.

Evolution and Human Identity

For many people, understanding evolution transforms the way they see themselves. It’s a humbling thought—that we are the product of countless generations of animals, that our hands are modified fins, our genes shared with fish, worms, and fungi. But it is also profoundly unifying.

We are not separate from nature. We are nature. We are cousins to the gorilla, kin to the sunflower, and distant relatives of the bacteria in our own mouths. Evolution reveals the deep connection between all life. It erases boundaries and builds empathy.

This understanding also brings responsibility. As the dominant species on Earth, with the power to destroy or protect life’s diversity, we must act not as conquerors, but as stewards. Evolution has gifted us with intelligence—but also with the capacity to care.

The Endless Adventure

Evolution is not a force of the past, nor a concept limited to textbooks. It is the most profound story we know—a story of change, resilience, failure, and beauty. It is the reason there are birds that can navigate by the stars, trees that can live for thousands of years, and eyes that can behold all of it.

The diversity of life on Earth is not just an accident; it is a masterpiece billions of years in the making. Every organism is a sculpture shaped by time, environment, and struggle. And every one is still being shaped, even now.

To study evolution is to read the autobiography of the Earth, written in DNA and fossils, in beaks and wings, in songs and colors and bones. It is to witness the universe becoming aware of itself, one generation at a time.

And it is to recognize that we, too, are part of that ongoing process—not its final act, but just one note in an ancient, never-ending symphony.