Night falls across the world. In the dense jungles of the Amazon, a jaguar stretches and settles into a nap. In a suburban backyard, a dog twitches its legs and softly growls in its sleep. Beneath the ocean waves, an octopus suddenly flashes a kaleidoscope of colors and then grows still again. These moments, scattered across the globe, seem mundane on the surface. Yet they are tiny windows into one of the most mysterious and surprisingly emotional aspects of life on Earth: dreaming.

Humans have long marveled at their dreams—those fleeting, surreal adventures that play across our minds while we sleep. But are we alone in this inner theater? Do other animals dream? And if so, what do they see, feel, or remember during their slumber? For decades, scientists had only scraps of evidence and scattered anecdotes. Today, thanks to breakthroughs in neuroscience, sleep studies, and behavioral research, we are finally beginning to pull back the veil—and the answers are more extraordinary than we imagined.

The Discovery of REM Sleep: A Shared Pattern

In the 1950s, researchers Eugene Aserinsky and Nathaniel Kleitman made a groundbreaking discovery: during certain phases of sleep, human eyes dart rapidly beneath closed lids, the body becomes temporarily paralyzed, and brain activity mimics that of wakefulness. This stage, dubbed rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, became closely associated with dreaming. People awakened during REM phases often reported vivid, narrative dreams, filled with sights, sounds, and emotions.

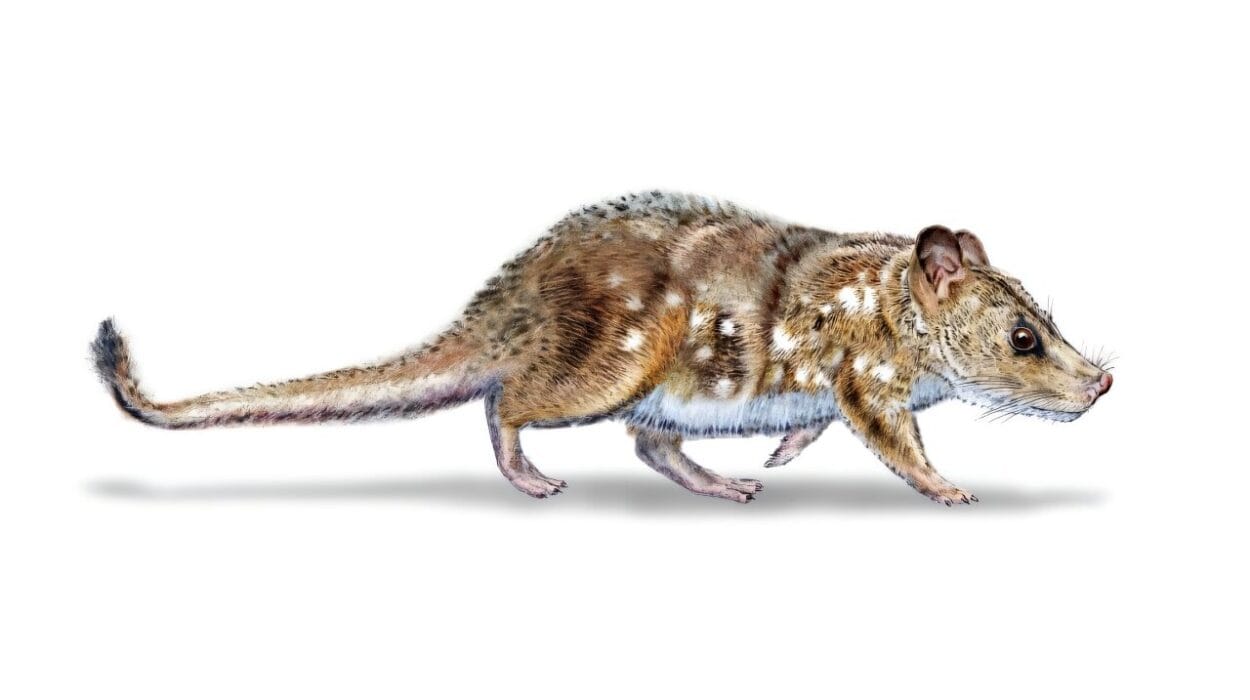

The discovery of REM sleep sparked a profound question: did other animals experience it too? Over time, scientists began observing similar phenomena in a surprising variety of species. Cats, dogs, rats, birds—even reptiles—have all been shown to undergo REM-like states. Their bodies twitch. Their breathing patterns change. In some cases, they vocalize, paddle their legs, or display facial expressions.

These observations were not merely suggestive; they hinted at an astonishing continuity across the animal kingdom. Not only did animals sleep—many of them dreamed. But what exactly were these creatures dreaming about? And could their dreams resemble ours in content, purpose, or emotion?

Into the Mind of a Sleeping Cat

One of the most iconic early experiments that fueled this line of inquiry came from French neuroscientist Michel Jouvet in the 1960s. Jouvet studied the sleep patterns of cats and found that during REM sleep, the brainstem sends signals that suppress muscle movement—a mechanism preventing the sleeper from physically acting out their dreams. He surgically disabled this mechanism in a group of cats, allowing them to move freely during REM.

What he observed was uncanny. The cats stood up, stalked invisible prey, swatted at the air, and even leapt forward—as though hunting in their dreams. This behavior was not random muscle activity but structured, purposeful movement. Jouvet believed these cats were “dream-enacting,” reliving experiences from their waking life.

If cats could replay real-world memories in dreams, could other animals do the same? This was no longer idle speculation. By the 1990s, advances in brain imaging and electrophysiology allowed scientists to map how neurons fired during sleep. The findings were startling.

The Rodent Revolution: Dreaming in the Lab

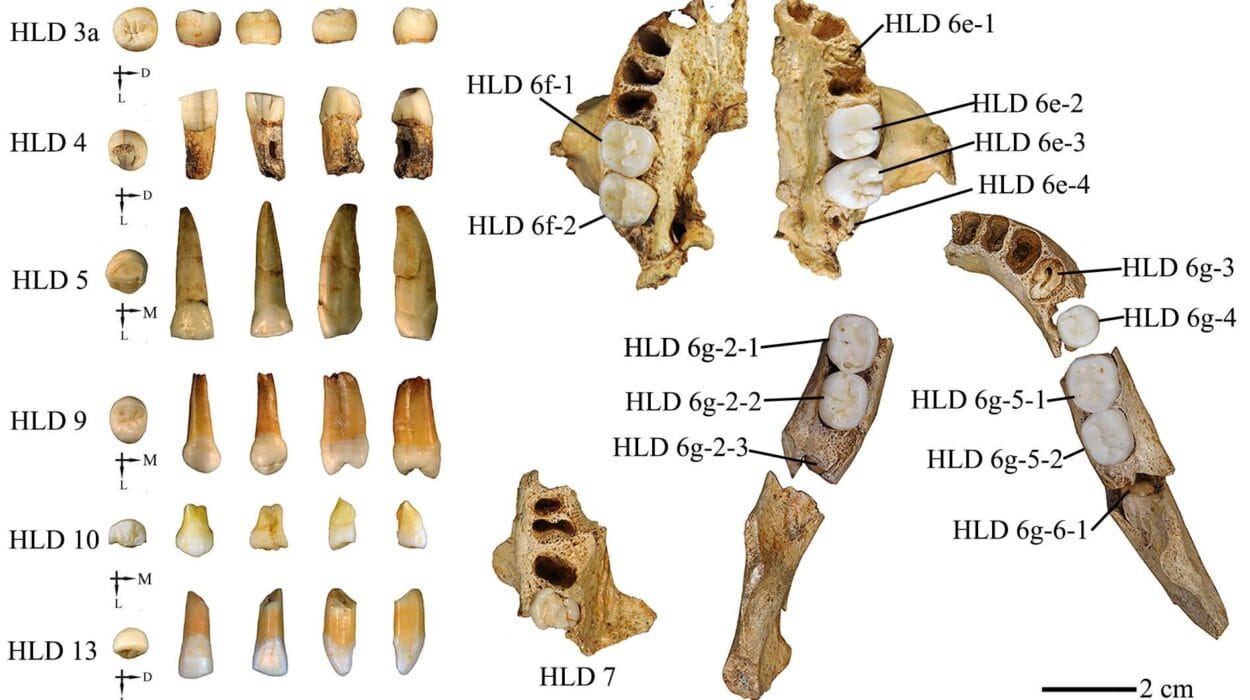

At the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, neuroscientist Matthew Wilson conducted a series of influential experiments on rats navigating mazes. As the rats ran through these mazes during the day, researchers recorded the firing patterns of neurons in the hippocampus—a brain region crucial for spatial memory and navigation. Each step of the maze created a distinct “neural signature,” a sequence of firing cells that encoded specific places and routes.

But what stunned researchers was what happened at night. While the rats slept, those same patterns of neural firing reappeared—often in the same sequence and sometimes in a compressed time frame. In essence, the rats were replaying their maze-running experiences in their dreams.

In one experiment, Wilson and his team played audio tones while rats navigated a maze and then again during their sleep. The rats’ brains responded to the tones by activating the same navigation circuits, suggesting that dreams could be cued, influenced, and even altered by environmental triggers.

These studies showed more than just reactivation of memories. They suggested that rats—creatures we rarely credit with inner lives—were mentally reliving their days, consolidating memories, and perhaps even preparing for future experiences. It was, in effect, a form of dreaming remarkably similar to that of humans.

Birds and the Songs of Sleep

Songbirds offered another compelling window into the dreaming lives of animals. Zebra finches, for instance, learn their songs through trial and error, mimicking adult calls over time. Neuroscientists discovered that when these birds sleep, the same brain areas involved in singing become active again. Their vocal muscles sometimes even twitch in tandem with these bursts of neural activity.

One study, led by Daniel Margoliash at the University of Chicago, found that when young finches slept, their brains appeared to “rehearse” songs they were still learning. The dreams were not random; they were structured, goal-oriented, and tied to the bird’s social and developmental needs.

Sleep, in this context, became more than rest. It was rehearsal. Memory. Practice. In the avian world, dreams were helping shape the self.

Dogs, Horses, and the Emotional Side of Dreams

Ask any dog owner whether their pet dreams, and you’re likely to get an enthusiastic “yes”—often with a story of paws twitching or muffled barks in the night. While anecdotal, these stories align with scientific findings. Dogs, like humans, enter REM sleep regularly. Observations have shown them twitching, moving their legs, and whimpering during these phases, behaviors that may mirror chasing, playing, or social interactions.

Canine cognition expert Stanley Coren has suggested that dogs likely dream about dog-like experiences: playing with their owners, chasing squirrels, or navigating familiar environments. Larger breeds may have longer dreams, while puppies, with their rapidly developing brains, appear to dream more frequently.

Horses, too, have been observed displaying facial expressions and muscular twitches during REM. Even elephants—known for their intelligence and memory—have REM sleep, though far less than humans. In captivity, elephants have been seen lying down, their trunks curling gently as they sleep, suggesting a level of vulnerability and emotional depth that sleep researchers find significant.

The emotional resonance of animal dreams is an open question, but growing evidence suggests that dreams may serve not only memory consolidation but also emotional regulation. In humans, REM sleep is associated with processing emotions, coping with trauma, and strengthening social bonds. It’s not a stretch to believe that animals, especially social mammals, may benefit in similar ways.

The Octopus Enigma

Perhaps the most surprising dreamer in recent scientific literature is the octopus. Cephalopods are not mammals. They are invertebrates with radically different brain architectures. Yet they are remarkably intelligent, capable of problem-solving, tool use, and even deception.

In 2019, Brazilian scientists captured video footage of an octopus sleeping—and displaying sudden, dramatic shifts in skin color and texture. These shifts mirrored patterns the octopus used when hunting, hiding, or displaying threat postures while awake. The researchers proposed that the octopus might be experiencing a kind of REM sleep, complete with visual dream-like imagery.

The idea that an animal so evolutionarily distant from humans might dream challenges our assumptions about consciousness. It suggests that dreaming may have evolved more than once and may serve deep biological functions not limited to mammals.

Why Do Animals Dream?

The question of whether animals dream has, in many ways, already been answered: they do. But why they dream remains an active and profound area of inquiry. For humans, dreams help us process emotions, encode memories, and imagine future possibilities. Could the same be true for animals?

The leading theories fall into several categories:

Memory Consolidation: Many studies support the idea that animals, like humans, use dreams to replay and strengthen daytime experiences. This helps with learning, especially in young or cognitively complex species.

Emotional Processing: REM sleep appears to modulate emotional states. In social animals, dreaming may help navigate group dynamics, recover from stress, or prepare for future interactions.

Survival Simulation: Some researchers propose that dreams function as “virtual reality,” allowing animals to practice behaviors—like hunting or fleeing—without real-world risk.

Neurological Maintenance: On a more fundamental level, dreams may help maintain neural pathways, especially in growing animals. This could explain why infants (human and non-human) dream more frequently than adults.

Each of these functions supports the idea that dreaming is not an evolutionary accident but a vital, active process—shared across species lines and shaped by the cognitive needs of each animal.

A Continuum of Consciousness

Dreaming, then, may be the clearest indication yet that consciousness is not binary. It is not something humans possess while animals do not. Rather, it exists along a continuum. Different species have different types of dreams, shaped by their perception, environment, and evolutionary pressures.

This realization forces us to reconsider long-held boundaries. If dogs can dream of their owners, if birds rehearse songs in sleep, if octopuses recall camouflage strategies in a REM-like state, then what else do they feel? Remember? Regret? Plan? Love?

Philosopher Thomas Nagel once famously asked, “What is it like to be a bat?” The question remains unanswerable in a strict sense, but neuroscience now allows us to edge closer. Through dreams, animals may reveal the outlines of their inner lives—not just how they behave, but how they experience.

Ethical Ripples

With this knowledge comes responsibility. Understanding that animals may have vivid inner worlds—and even emotional dreams—forces a deeper reflection on how we treat them. It challenges practices in farming, research, and captivity. Can we still justify keeping intelligent animals in barren cages, knowing they may dream of open fields, companions, or fears?

In laboratories, scientists have begun to reframe animal research guidelines, considering not only physical welfare but psychological enrichment. Sleep cycles are increasingly respected in zoo design. Companion animals are given toys, music, and play, all of which may enrich their waking and dreaming lives alike.

The science of animal dreaming is not just about curiosity; it is about compassion.

Into the Dreaming World

To dream is to be alive in a way that transcends the physical. It is to carry memories across time, to rehearse joys and fears, to traverse imagined landscapes. That dogs, rats, birds, and octopuses may share in this strange, nightly voyage is both humbling and awe-inspiring.

It reminds us that the division between humans and other animals is not a chasm, but a thread—woven tightly through our shared biology, experience, and sleep. The animal mind, once thought inscrutable, now opens to us in glimmers and sparks of neural fire, in the rustle of sleeping paws, the ripple of sleeping wings, the shifting skin of a slumbering cephalopod.

We may never know exactly what our fellow creatures see when they dream. But science has taught us this: they do dream. And in that dreamscape, they live, feel, remember, and become themselves again and again.

And perhaps, in their dreams, they are just like us—sailing through stories in the darkness, lit only by the flickering light of a sleeping mind.