On a warm spring morning, when blossoms unfurl and sunlight turns nectar into golden promises, you might stand near a flowering meadow and hear it—a gentle, vibrating hum. Bees move like flickers of light from bloom to bloom, seemingly chaotic, yet somehow perfectly coordinated. Watch long enough, and you realize there is more than just buzzing and flying. There is meaning here, a form of speech without words, a conversation carried out not in sound but in movement.

For centuries, humans marveled at the mysterious efficiency of honeybees. How could these tiny insects, with brains no bigger than a grass seed, locate distant flower patches and guide thousands of sisters to them with astonishing precision? The answer lay hidden in the hive, invisible to human eyes, until a patient scientist and a determined group of bees revealed one of nature’s most beautiful secrets: the language of dance.

This is not metaphor. Bees truly dance to communicate, performing intricate, coded movements that transmit complex information about the world beyond the hive. Their choreography is as nuanced as poetry, as precise as mathematics, and as vital as the very survival of their colony. Understanding this dance is like listening to a whisper of evolution itself—a message carried through millions of years of survival and cooperation.

Life Inside the Hive: A Superorganism at Work

To understand why bees dance, we must first enter their world. A beehive is not just a cluster of insects; it is a superorganism—a single living entity made of thousands of individuals working in harmony. Inside, roles are carefully divided. The queen lays eggs, drones seek queens from other colonies to spread genetic diversity, and worker bees—females without reproductive powers—build wax cells, care for larvae, defend the hive, and forage for food.

Foragers are the explorers. Each day, they venture out into landscapes that can stretch kilometers from the hive, searching for nectar-rich flowers. This is no small task. The world is vast, resources shift daily, and the survival of thousands depends on efficiently finding and exploiting these sources. If one bee simply brought food back alone, the colony would starve. Information must be shared, rapidly and accurately.

This is where the language of dance emerges—a bridge between individuals, a shared map etched not on paper but in movement.

A Discovery Hidden in Plain Sight

For centuries, beekeepers noticed odd behavior when foragers returned from successful trips. The bees would drop their loads of nectar and then begin moving in strange, deliberate patterns on the honeycomb. Other bees crowded around, antennal tips quivering, following the movements as if reading a secret script. But what did it mean?

The puzzle endured until the mid-20th century, when an Austrian zoologist named Karl von Frisch devoted years to careful observation and experimentation. Through meticulous study, he uncovered a truth that stunned the scientific world: these dances were not random. They were a complex form of symbolic communication, a way to tell others the direction, distance, and even quality of a food source.

Von Frisch’s groundbreaking work earned him a Nobel Prize in 1973, but more than that, it opened a window into an alien yet astonishingly sophisticated mind. Bees were not just instinct-driven automatons. They were capable of abstract communication, a trait once thought unique to humans.

The Language of Motion: Round Dances and Waggle Dances

Bees use two primary dances, each serving a different purpose. Imagine standing inside the hive as a returning forager begins her performance. Other bees form a circle around her, their bodies vibrating with anticipation.

When food is nearby—within about 50 meters—the dancer performs a round dance, a simple circling motion. She moves first in one direction, then reverses. This tells her sisters only that something good is close; no direction is needed because they can find it easily by scent once they fly outside.

But when food is farther away, a more elaborate and mesmerizing display unfolds: the waggle dance. The bee runs forward in a straight line while shaking her abdomen vigorously—this is the waggle phase—then loops back around to repeat the pattern, tracing a figure-eight path. The angle of the waggle run relative to gravity indicates direction. If she waggles straight up, the food lies in the same direction as the sun. If she angles left or right, the food is to that side relative to the sun’s position.

The duration of the waggle phase encodes distance. A longer waggle means a farther journey. The intensity of the wiggle signals quality—vigorous shakes mean richer nectar. To watch a waggle dance is to watch an insect draw a map with her body, describing a location miles away to creatures that have never seen it.

This information is astonishingly accurate. Researchers have released bees in unfamiliar terrain and found that their sisters, following dance instructions alone, could fly straight to the spot without any guide.

How Bees Read the Dance

The communication doesn’t end with the dancer. The listening bees engage with her actively, touching her with antennae, sensing vibrations, and even tasting nectar samples she shares. This exchange helps them gauge not just direction and distance, but the flavor and energy value of the food source.

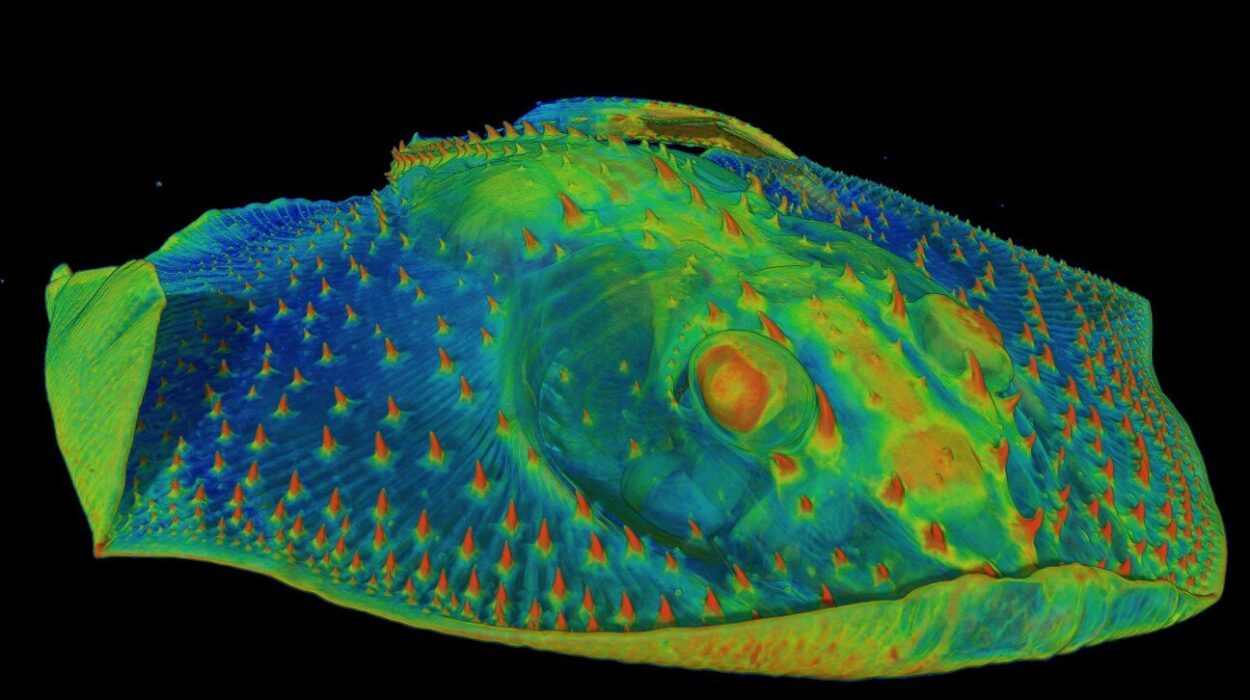

Bees do not see the dance the way we see human gestures. Inside the dark hive, vision is limited. Instead, they feel it. The waggle generates specific vibrations transmitted through the comb. The moving air, the hum of wings, and pheromonal cues combine into a multisensory message. To a bee, the dance is not merely visual—it is an immersive, tactile experience.

Once they understand, the recruits take flight, guided by sunlight and polarized light patterns in the sky, which they can detect through specialized eyes. They use the dance’s encoded instructions to orient themselves and locate the food source with stunning precision.

The Sun Compass and the Geometry of Navigation

Underlying the waggle dance is an incredible navigational ability. Bees use the sun as a compass, adjusting for its movement throughout the day. When a dancer angles her waggle 30 degrees to the right of vertical, it means “fly 30 degrees to the right of the sun.” As the sun moves, bees automatically update their internal calculations, ensuring the dance remains accurate even hours after the original forager discovered the source.

This requires an internal biological clock—a circadian rhythm finely tuned to the sun’s arc. Experiments have shown that if you shift a bee’s internal clock by manipulating light exposure, her dances shift accordingly, proving that they encode temporal as well as spatial information.

The complexity rivals human navigation. A bee can integrate directional cues, distance, time of day, wind conditions, and previous landscape knowledge, then translate all this into a short dance that other bees can interpret instantly. In computational terms, it is a high-efficiency information-sharing algorithm evolved millions of years before humans invented written language.

Beyond Food: Other Meanings of the Dance

Though primarily used to indicate food, bee dances can convey other messages. Scout bees use similar movements to recruit swarms to new nesting sites when colonies divide. Here, multiple scouts dance for different sites, and the hive engages in a form of collective decision-making. Bees compare dances, gradually converging on the best location through a democratic process.

These swarming dances involve debate-like interactions—bees interrupt, test, and even “head butt” dancers they disagree with, suppressing weaker options until consensus is reached. Remarkably, this process avoids deadlocks and reliably leads to optimal choices, inspiring research into swarm intelligence and collective robotics.

The Chemical Chorus: Dances and Pheromones

Bee communication is not only about movement. While dancing, foragers release pheromones—chemical signals that complement the information conveyed by motion. The Nasonov pheromone helps attract nestmates to resources, while other scents signal alarm or readiness to swarm.

Inside the hive, these pheromones mix with vibrations from the dance, creating a layered language. It is as if bees combine body language, scent messages, and even acoustic cues into a unified, multidimensional communication system. This integration ensures resilience—if one channel is disrupted, others still transmit crucial information.

The Role of Learning and Culture

Young bees do not instinctively know how to interpret dances. They learn by observing and following experienced foragers. Studies show that naive bees initially struggle with dance cues but gradually improve, suggesting a form of cultural transmission.

Even more fascinating, different honeybee species and populations have variations in their dances, akin to dialects. Some use steeper angles or longer waggles for similar distances. When bees from different colonies mix, they sometimes misunderstand each other at first but can adapt over time. This flexibility hints at an evolutionary foundation for learning and adaptation similar to cultural traits in higher animals.

The Evolutionary Origins of the Dance

Why did bees evolve such sophisticated communication? The answer lies in the efficiency of resource exploitation. Flowers bloom unpredictably, scattered across wide areas. A colony’s survival depends on rapidly mobilizing foragers to the best sources.

Primitive ancestors of honeybees likely used simpler cues—scent trails or buzzing sounds. Over millions of years, as colonies grew larger and competition intensified, natural selection favored individuals who could share precise spatial information. The dance emerged as a solution, allowing complex societies to function as a single, coordinated organism.

Fossil evidence and studies of closely related species suggest the dance’s roots are ancient, possibly over 20 million years old. It has stood the test of time, unchanged in its fundamentals because it is remarkably efficient.

Threats to the Dance: Modern Challenges

Today, bees face unprecedented challenges: habitat loss, pesticides, climate change, and diseases. These pressures can disrupt their ability to forage and dance effectively.

For example, neurotoxic pesticides impair bees’ navigation, causing them to return to the hive confused or not at all. Without accurate foraging information, colonies weaken. Climate-driven changes in flowering patterns also confuse the timing and effectiveness of waggle dances, as bees struggle to adapt to shifting nectar landscapes.

Understanding bee communication is not just a scientific curiosity—it is crucial for conservation. By decoding how bees share information, researchers can design landscapes and agricultural practices that support their natural foraging behavior, ensuring their survival and, by extension, our own food security.

The Human Connection: Lessons from Bees

The dance language of bees is more than an insect marvel; it holds lessons for humanity. It shows that complex, symbolic communication can evolve in tiny brains, challenging assumptions about intelligence and language. It demonstrates how cooperation and information-sharing enable small creatures to achieve feats impossible for individuals alone.

Engineers and computer scientists study bee dances to design algorithms for autonomous drones, search-and-rescue robots, and efficient delivery systems. Philosophers ponder what bee communication reveals about consciousness. Writers and artists find inspiration in the idea of insects speaking through movement, embodying harmony between individual freedom and collective purpose.

On a deeper level, bee dances remind us that language need not be spoken or written to be powerful. Meaning can flow through vibrations, scents, and motion—silent, unseen, yet perfectly understood by those attuned to it.

A Final Dance Beneath the Sun

Imagine standing at the entrance of a thriving hive on a summer afternoon. Bees zip past in golden arcs, carrying messages of abundance. Inside, a returning forager begins her waggle dance. The dark hive vibrates with the pulse of her abdomen. Sisters gather, touching her, sensing her excitement. Within moments, a wave of recruits surges out toward the waiting fields.

This is communication at its most primal and elegant—a code refined by nature’s genius, a story told without words that sustains entire worlds of flowers, fruit, and honey. The bees dance, and through their dance, life blossoms across meadows and orchards.

Long after the dancer has flown her last journey, long after human civilizations rise and fall, the hidden language of bees will continue—a quiet, graceful ballet beneath the sun, guiding tiny explorers across endless landscapes, ensuring survival through movement and unity.

It is a reminder that even the smallest creatures possess wisdom etched in rhythms older than history, a language we have only just begun to understand, a dance that whispers of connection, cooperation, and the fragile beauty of our shared planet.