Imagine standing on the banks of the Upper Rhine in what is now southwestern Germany — not amid vineyards or quiet villages, but in a landscape echoing with the bellows of hippos. It seems impossible. Hippos belong to Africa, to the warm shallows of the Nile or the muddy lakes of the Serengeti. Yet, new research reveals that tens of thousands of years ago, these same mighty river dwellers thrived in the heart of Ice Age Europe.

An international team of scientists led by the University of Potsdam and the Reiss-Engelhorn-Museen Mannheim, in collaboration with ETH Zurich and the Curt-Engelhorn-Zentrum Archäometrie, has uncovered astonishing evidence that hippos survived in central Europe far longer than anyone thought. Their study, published in Current Biology, reveals that common hippos (Hippopotamus amphibius) inhabited the Upper Rhine Graben between approximately 47,000 and 31,000 years ago — well into the last Ice Age.

For decades, scientists believed that hippos vanished from Europe around 115,000 years ago, as the continent cooled and glaciers advanced. The discovery upends that assumption and paints a far more complex picture of Ice Age climates, ecosystems, and survival.

Hippos in the Cold

At first glance, the idea seems absurd. Hippos are creatures of heat — thick-skinned, water-loving giants that need warm climates to survive. How could they possibly have endured the harsh conditions of an Ice Age? The answer lies in the details of Europe’s ancient climate.

The last Ice Age, or Weichselian glaciation, was not a single unbroken deep freeze. It fluctuated between cold and relatively mild phases, during which temperatures and ecosystems could briefly resemble today’s. During one of these milder interludes, the Upper Rhine region offered a haven — a patch of warmth and wetlands where hippos could graze and wallow.

Their bones, preserved in gravel and sand deposits, have become time capsules of this lost world. According to Dr. Ronny Friedrich of the Curt-Engelhorn-Zentrum Archäometrie, who specializes in age determination, the preservation was remarkable: “It’s amazing how well the bones have survived. At many skeletal remains, it was possible to take samples suitable for analysis — that is not a given after such a long time.”

The Science Beneath the Bones

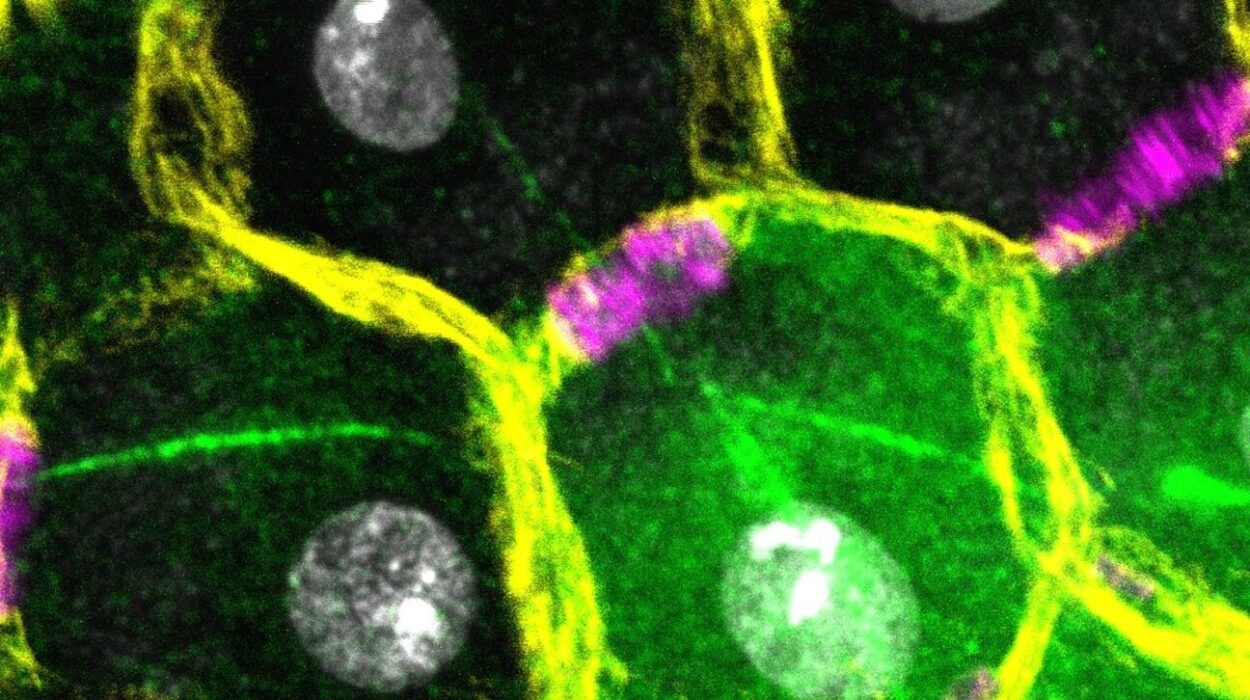

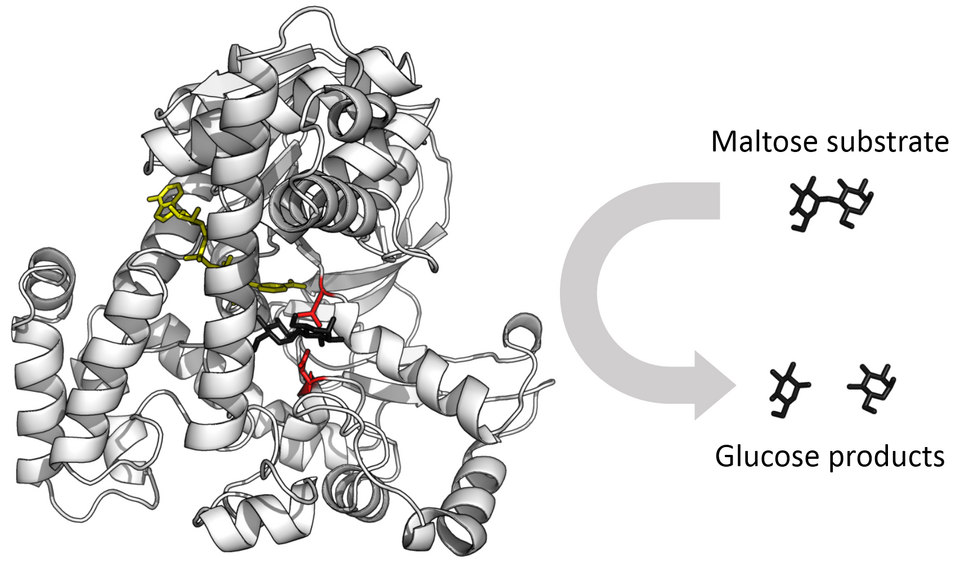

To unlock the story of these Ice Age hippos, scientists used a powerful combination of paleogenomics and radiocarbon dating. By sequencing ancient DNA, they were able to compare the genetic material of the European specimens with that of modern African hippos. The result was astonishing: the Ice Age hippos were not a distinct European species but belonged to the same species that still splashes through African rivers today.

Radiocarbon dating confirmed that these animals lived between 47,000 and 31,000 years ago — long after they were thought to have disappeared from Europe. This means that while mammoths and woolly rhinos were roaming the frozen plains, hippos were living nearby in warmer microclimates, sharing the same landscape but thriving in entirely different ecological niches.

Further genome-wide analysis revealed another fascinating detail: these European hippos had very low genetic diversity. This suggests that their population was small and isolated — a remnant group clinging to survival at the edge of their natural range.

A Paradox of Ice and Heat

The coexistence of tropical hippos and Ice Age megafauna like mammoths challenges traditional views of Europe’s ancient environment. It reveals that the Ice Age was not uniformly cold; instead, it was a patchwork of varying climates and habitats. Some regions remained mild enough to support species that we typically associate with much warmer environments.

Dr. Patrick Arnold, the study’s first author, summarizes the revelation clearly: “The results demonstrate that hippos did not vanish from middle Europe at the end of the last interglacial, as previously assumed. Therefore, we should re-analyze other continental European hippo fossils traditionally attributed to the last interglacial period.”

In other words, Europe’s Ice Age was not a single frozen world but a mosaic of conditions — and hippos, with their remarkable adaptability, managed to find a foothold in one of its gentler corners.

The Upper Rhine Graben: A Window into the Past

The Upper Rhine Graben, stretching across modern-day Germany and France, is more than just a geographic region — it is one of Europe’s richest natural archives of ancient life and climate. Layers of gravel, sand, and silt hold the bones of animals that lived hundreds of thousands of years ago, preserving the ebb and flow of ecosystems through shifting ages.

Within these sediments, scientists have discovered fossils from mammoths, woolly rhinoceroses, cave lions, and now hippos — each a clue to the region’s environmental transformations. The study forms part of the broader “Eiszeitfenster Oberrheingraben” (Ice Age Window Upper Rhine Graben) project, which seeks to reconstruct climate and ecological history over the past 400,000 years.

For Prof. Dr. Wilfried Rosendahl, general director of the Reiss-Engelhorn-Museen Mannheim and leader of the project, the findings highlight the richness of Ice Age research: “The current study provides important new insights which impressively prove that the Ice Age was not the same everywhere. Local peculiarities taken together form a complex overall picture — similar to a puzzle.”

Each new discovery adds a piece to that puzzle, reshaping how we understand not just the climate of the past but the resilience of life itself.

The Secret Life of Ice Age Hippos

The image of hippos wandering through Ice Age Europe sparks the imagination. They would have lived along the banks of broad rivers and wetlands, feeding on reeds and grasses. In summer, they might have basked in temperate sunshine; in winter, they may have migrated short distances or sheltered in lowland valleys where the water did not freeze entirely.

They were not alone. Mammoths, woolly rhinos, horses, and reindeer roamed the same landscapes, forming a dynamic ecosystem that could shift dramatically with each climatic pulse. The presence of hippos among these cold-adapted species suggests that warm refuges — ecological pockets protected from the worst of the Ice Age — existed even in central Europe.

These refuges may have acted as sanctuaries, allowing some species to survive longer than expected. When the climate cooled again, the European hippos eventually vanished, unable to adapt to prolonged freezing. Their bones remained buried, waiting to be rediscovered tens of thousands of years later.

Rewriting the Story of the Ice Age

This discovery forces scientists to rethink not only the timeline of hippo extinction in Europe but also the complexity of Ice Age environments. It suggests that species distribution was far more fluid than previously believed, with animals shifting their ranges as climates fluctuated.

It also underscores the power of modern science to resurrect lost chapters of Earth’s history. By combining genetic and radiocarbon techniques, researchers can now trace ancient lineages and reveal stories that fossils alone cannot tell. The hippos of the Upper Rhine Graben are one such story — a testament to endurance, adaptation, and the intricate interplay between life and climate.

As Dr. Rosendahl notes, the study opens the door to further exploration: “It would now be interesting and important to further examine other heat-loving animal species attributed so far to the last interglacial.” If hippos survived deep into the Ice Age, perhaps other warm-climate animals did too, hidden in forgotten corners of prehistoric Europe.

Lessons from a Lost World

Beyond the scientific wonder, this discovery carries a quiet lesson about resilience and change. Life, as biology constantly shows us, has an extraordinary ability to adapt. Even in times of dramatic environmental upheaval, some species find a way to persist — sometimes in unexpected places.

The hippos of Ice Age Germany remind us that nature’s boundaries are rarely fixed. Climate, geography, and biology are in constant conversation, shaping and reshaping the possibilities of life. Their story bridges two worlds — the frozen landscapes of mammoths and the sunlit rivers of Africa — showing that survival often thrives in the margins, where life refuses to give in.

The Echo of Giants

Today, hippos are confined to the rivers and lakes of sub-Saharan Africa, their populations threatened by habitat loss and hunting. Yet their bones in European soil tell a different story — one of expansion, adaptability, and persistence through time. They are a living link to a forgotten Europe, where cold winds swept over icy plains, and beneath those skies, the shadows of giant hippos moved through ancient waters.

The Ice Age was not as simple as a world locked in ice; it was a living, breathing mosaic of extremes. And somewhere in that mosaic, in the warmth of the Upper Rhine, hippos found a home.

A Past That Still Lives

The story of the Ice Age hippos is more than a paleontological surprise. It is a reminder that our planet has always been dynamic — that climates shift, species migrate, and ecosystems adapt. In understanding these past transformations, we glimpse the resilience of life and gain insight into our own changing world.

The bones of those long-vanished hippos whisper across millennia: life endures, even against the odds. Their discovery in the heart of Europe reminds us that the boundaries between past and present, between one climate and another, are not as distant as they seem. The world we know today is built upon the echoes of such forgotten worlds — and every fossil we unearth tells a story still unfolding.

More information: Patrick Arnold et al, Ancient DNA and dating evidence for the dispersal of hippos into central Europe during the last glacial, Current Biology (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2025.09.035